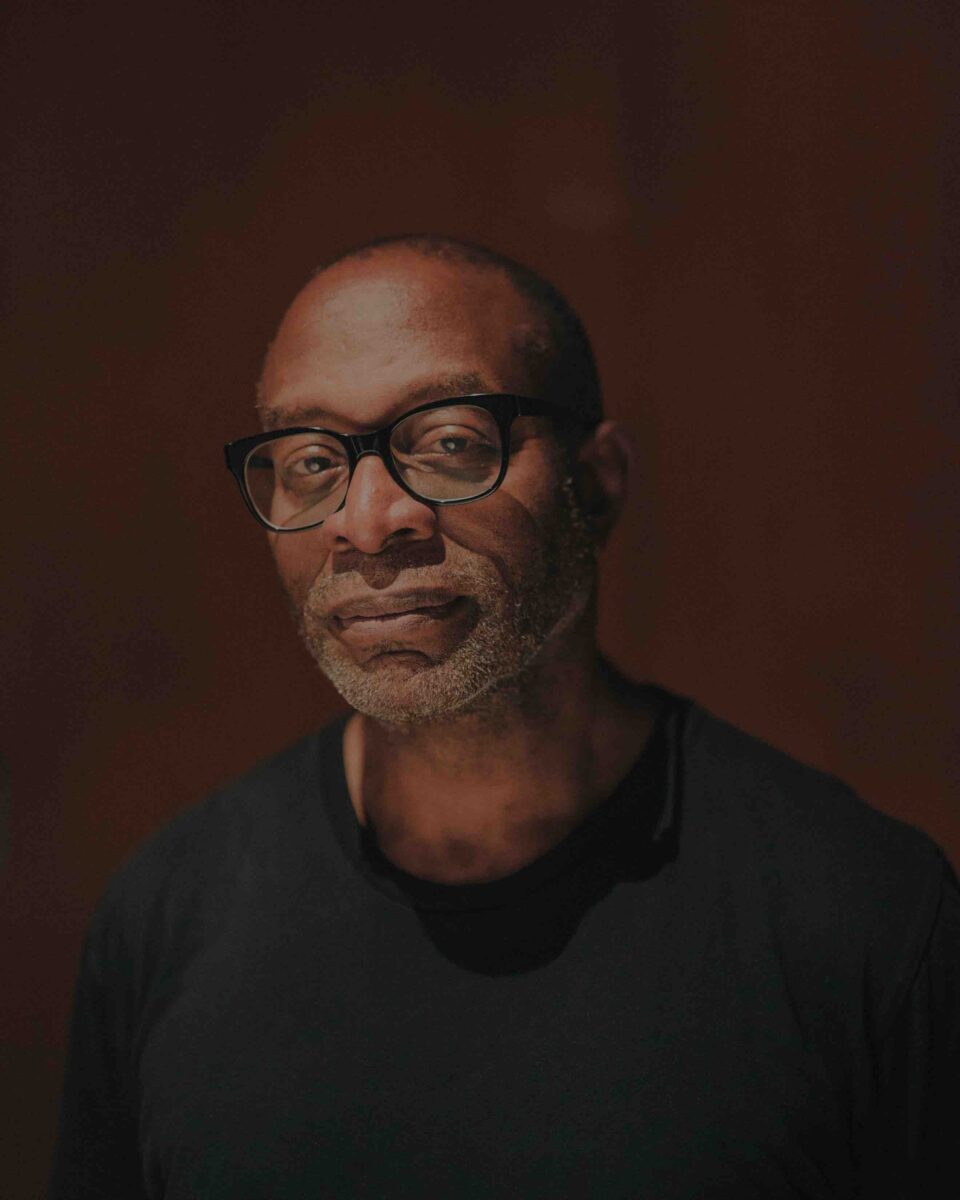

For seven albums between 1971 and 1978, keyboardist-composer Brian Jackson was a full collaborative partner in the spoken-word soul of griot Gil Scott-Heron. With their mix of driving jazz-funk and quiet, storming R&B—to say nothing of Scott-Heron’s world-weary, socio-focused poetry—the pair, often with the Midnight Band, acted as avatars to hip-hop’s jazzy, conscious vibe.

For all of his efforts, vision, and diligence, the free-minded Jackson—who’d been playing piano since his childhood in Brooklyn—never got the credit, as Scott-Heron had, for starting the televised revolution. Jackson states that he was never even given a decent chance to fully prove his solo chops, opting instead to gig with vibraphonist Roy Ayers, producer Gwen Guthrie, and singer Will Downing after he split from Scott-Heron.

Recently, however, Jackson’s name and jam-right has been given its flowers from producers/collaborators Ali Shaheed Muhammad of A Tribe Called Quest and Adrian Younge on Brian Jackson JID008, their 2021 trio work released on that pair’s Jazz Is Dead label. Now we have the BBE label stunner This Is Brian Jackson, Jackson’s first true solo work in over 20 years—and one presenting every funky, free, and soulful color in Jackson’s rainbow.

We spoke with Jackson from London where the keyboardist has been actively touring.

Let’s go all the way back to your Brooklyn roots. Didn’t you start as a drummer?

I wanted to play drums, but my mom wasn’t having it. Not in the apartment that we lived in, she wasn’t. She didn’t want us to get kicked out, and drumming was not the kind of thing you did if you wanted to hold onto your lease.

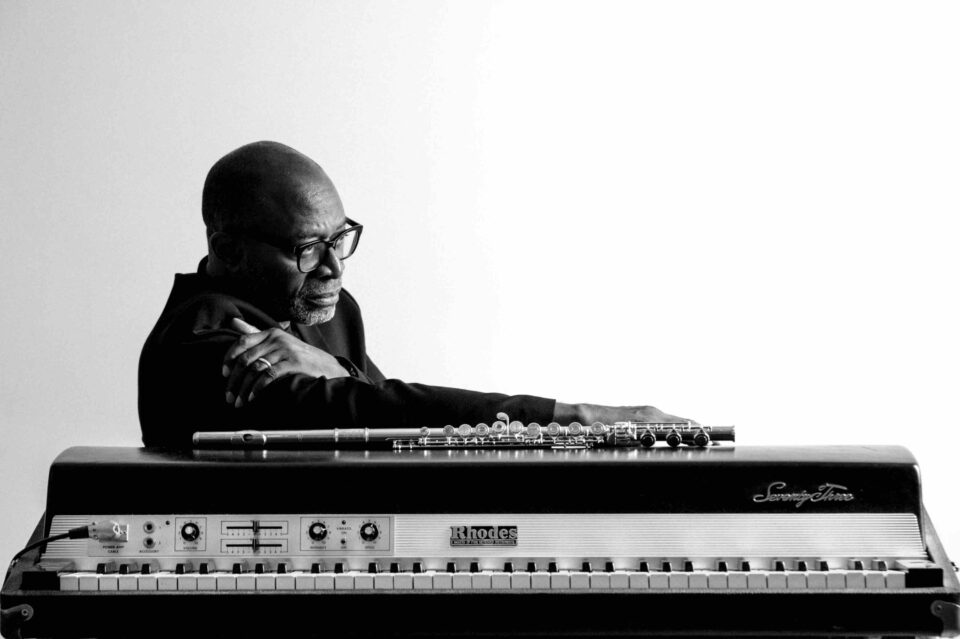

So why did flute and keyboards become your thing, besides keeping your lease intact?

My mother and I agreed on the piano. It wasn’t a tough sell. The flute came much later, when I had to stop playing sax after having severed a nerve in my shoulder. It was the classic doctor-patient scenario: “Doctor, it hurts when I do this.” “OK, so don’t do that.” Hence, the flute. It didn’t require me to have anything around my neck.

“I’m free as an artist. I don’t think toward what I should be doing. I think in terms of what I want to hear. I was and am lucky that my friends think just like me, so we can play free.”

To contain your talents in one genre or tag is foolish…

I’m glad you realize that.

...how did you develop the sonic palette you wound up moving forward with?

My parents had eclectic tastes—from European classical, to big band jazz, to crooners like Sinatra and Ella, to bop such as Max Roach. That was my environment. As I left home and branched out on my own, I found Motown, R&B, the rock of that era. That mixed up inside of me.

What was your first professional gig, and what do you recall about it?

It was at a church in Harlem, and I was young. I was doing some songs of my own, which was pretty great. I mixed in Bach for the churchgoers, even though I wasn’t really a church-going kid. I think I was 14 at the time. Later on, when I was 16, 17, and started working with Gil and the Black & Blues Band—which consisted of, like, 11 people—we got gigs. I actually was in three bands in college: that group, an avant-garde band dedicated to playing post-bop, and a Top-40 soul/R&B band that played for the student mixers on the weekends.

How much of the feeling for experimentation, then, figured into what you’re doing now?

I’m free as an artist. I don’t think toward what I should be doing. I think in terms of what I want to hear. I was and am lucky that my friends think just like me, so we can play free. There’s always a chance that you get stuck in a groove, even if you don’t realize that it’s happening. I do everything in my power to go beyond that.

You mentioned Gil—how do you think you would’ve developed if you two hadn’t continued on for such a long time?

I can’t imagine. I was leaning toward avant-garde jazz, when I met Gil, by the Black Arts Movement characterized in Brooklyn by Gary Bartz, Pharoah Sanders, and McCoy Tyner. By the same token, I was listening to Stevie Wonder and Earth, Wind & Fire, too. I don’t know that I would have gone in the direction I had with Gil if I’d stayed a solo instrumentalist. Working with Gil, I understood immediately that we were doing fully developed vocal-based tracks. That required a different discipline, which I had to apply myself to, and was happy to do it. It definitely changed the trajectory of where I think I was headed. I do think that Gil and I moved the needle for each other.

“Gil’s voice will always stay an influence on the way I sing. My whole approach to singing with him was to try and mimic his vocal inflections so that we would sound like the same person. That got ingrained in me. I couldn’t remove it if I wanted to.”

Coming out of the relationship with Gil, what did you get from working through the rhythm and tone of his voice that carried forward into your work?

Gil’s vocals and lyrics and his approach to writing—combining and blending different elements of folk music and more contemporary sounds—were my gauges as to how to go forward. When I stopped doing that with him, I was disappointed in myself because I’d evolved past that…even though, in some ways, I didn’t want to. Gil’s voice, the way he sang and what he sang, will always stay an influence on the way I sing. My whole approach to singing with him was to try and mimic his vocal inflections so that we would sound like the same person. That got ingrained in me. I couldn’t remove it if I wanted to.

So Gotta Play, your solo album from 2000. Looking backward, how does your first solo album beyond Gil sound and feel?

I’m deeply proud of it. The most interesting thing about Gotta Play for me was how it was regarded. It came about at a time when musicians were plying their craft in hip-hop. Jazz musicians were trying to graft elements of hip-hop into their music without really taking care of the seed, without seeing how it all really fit. It was as if they weren’t paying attention to what body part they were grafting onto what part of the torso. There was a lot of Frankenstein-ing going on. I had begun to be interested in hip-hop—so much so that I believed that I understood its evolution.

Well, you and Gil were its evolution, one of the larger aspects of how the flow of the spoken word became that of rap.

With that, I felt an obligation to link with it. What I wanted to do with Gotta Play was do something sincere. That didn’t come from a commercial aspiration. However, unfortunately, it came along at a time when there were a lot of jazz musicians who were incorporating that into their music. What I did got mixed into that moment, but if you listen carefully, you’ll hear that that’s not at all what I was trying to do.

Music is a process. You took a minute to do something on your own again. Not a fun question, but why? Was recording not a priority?

Far from it. Recording is one of my favorite things. The fact that I wasn’t doing more recording tells the whole story. I’d recorded some music upon leaving Gil’s Midnight Band in the ’80s. I went to 15 labels, all of whom turned me down. Not having an album or a label, for me, was like not having a career. Not having a career was not having money. So the best thing for me to do was get a job, which I did. That enabled me to do something that most musicians can’t do very often, which is say “no.” I said no to projects I didn’t feel and said yes to some really great projects, such as working with Kool & the Gang, producing Will Downing’s first album, co-producing and writing for Gwen Guthrie, and going on tour with Phyllis Hyman and Bobbi Humphrey. There were those moments where I got the chance to get away and do music I loved. I just didn’t do my own stuff. It didn’t make sense to me for a time.

“None of us had any preconceived notions as to what this would be—which is what I always try to do. I just let an album decide for itself what it will be.”

Interesting you mentioned hip-hop, because you worked with Adrian Younge and Ali Shaheed Muhammad, two men whose music colors way outside of conventional lines. How did you three unite in the first place, and what was that goal?

I can tell you that my awareness of hip-hop pretty much was triggered by groups such as A Tribe Called Quest, Digable Planets, and De La Soul. Muhammad was somebody who I had in my ear, in my mind, and in my heart for a very long time. We did studio sessions—an experiment on their part, and one that worked. It set the tone for everything they did after that, from our method of working to whatever it meant to them to work with older musicians who they felt connections with.

How did that JID008 collaboration act as a precursor to your new solo album?

I definitely benefited. It was the first album in forever that had my name on it—almost 20 years. It automatically generated attention because of everyone involved. When people heard it, they understood its unique qualities, how it bore the stamp of its producers. And then they got to consider my contribution to it. I’m happy and proud of this. This record came without constraints. None of us had any preconceived notions as to what this would be—which is what I always try to do. I just let an album decide for itself what it will be.

The songs on the new album, did they exist in the past?

Interestingly enough, I started work with [producer Daniel Collás] on this album in 2018 in Brooklyn. I’d been doing a residency at the Nublu Club in the East Village and we immediately started talking shop. Daniel asked me had I thought about producing an album, and I responded that I didn’t want to do one by myself, that I was sick of hearing my own production. I just needed a way out of my own head. He helped get me out of there, and took a chance.

The other thing you might be asking me is how these new songs actually came about. Two of them, oddly enough, had originally been recorded in the 1970s—never finished and never released. There was another song that I’d conceived in 1974 and simply lost the original. I recorded “Nomad” at Electric Ladyland studio but lost the masters. The interesting thing, then, is how I began to write the new album in the frame of mind of a Brian Jackson, in 2018, completing that album I started in the mid-’70s.

And how did the Brian Jackson of the 1970s fare in the 21st century?

It should have been much more challenging, right? But what I learned about myself is that I really haven’t changed that much. FL