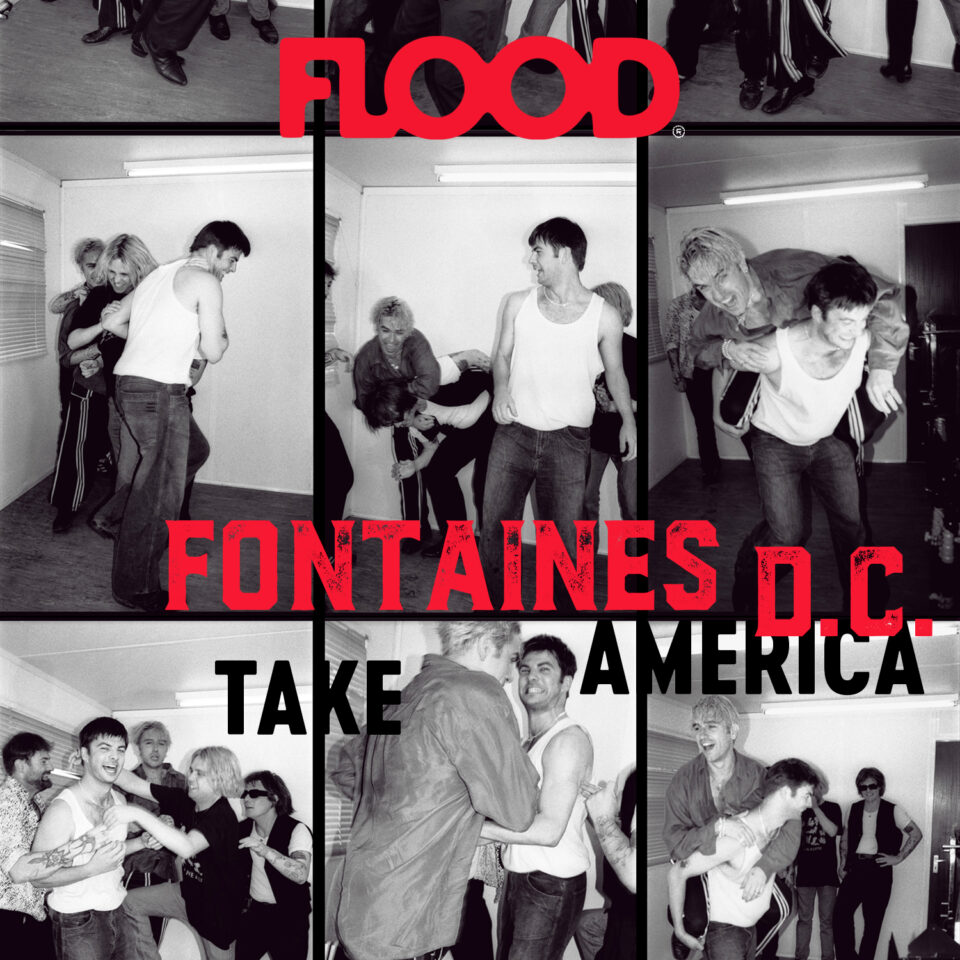

Irish post-punk quintet Fontaines D.C. have had a rub of the green in 2022. In April, they dropped their critically acclaimed third album Skinty Fia—an honest, painstaking love letter to Dublin—and embarked on a headlining tour of North America. The record is their most adventurous to date, a dynamic mix of tough and thoughtful tunes as well as a choral progression from their 2019 debut Dogrel, which found them sticking to raucous garage rock influence with rigid singing and sharp imagery that turned Ireland’s capital into a literary marvel.

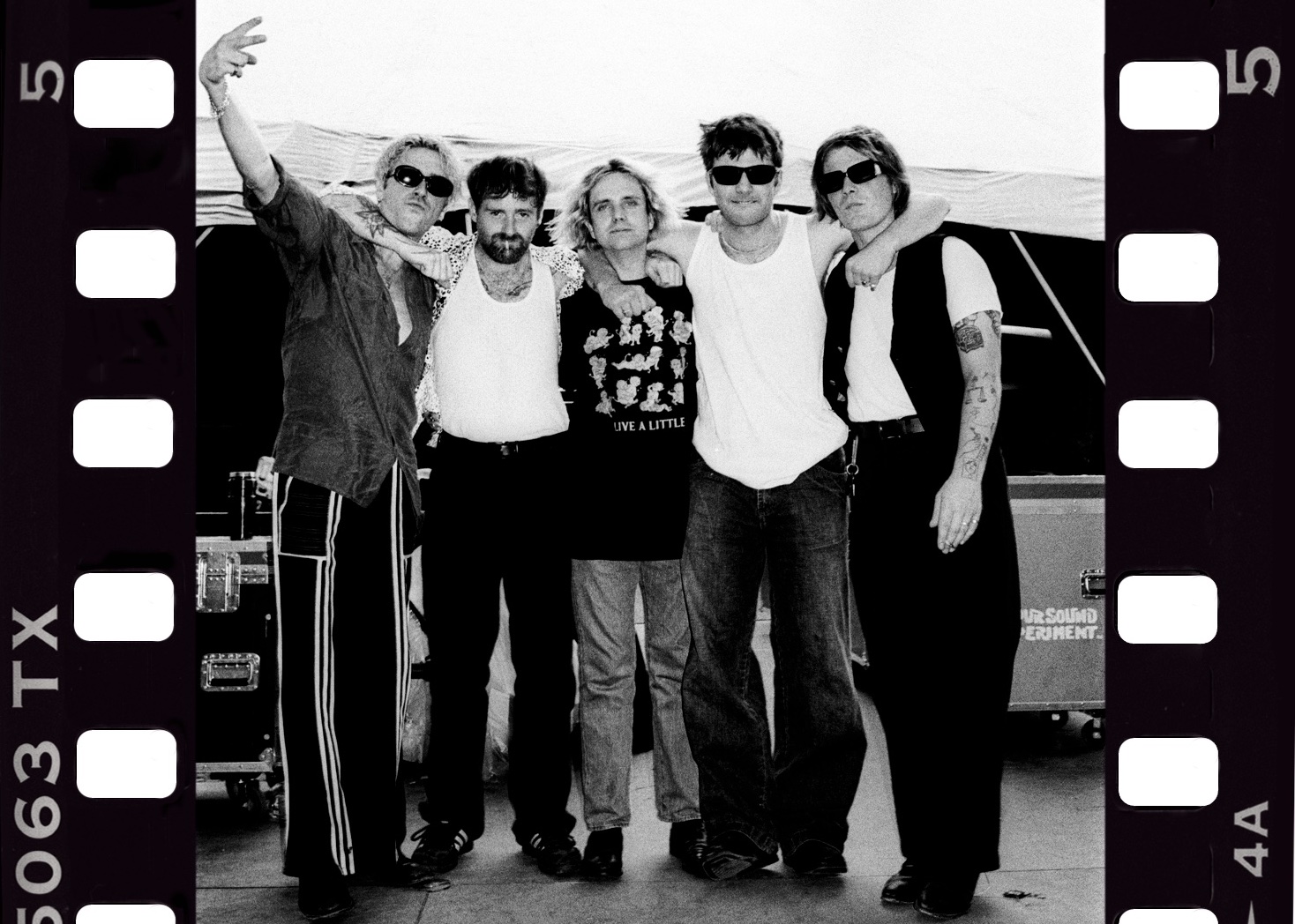

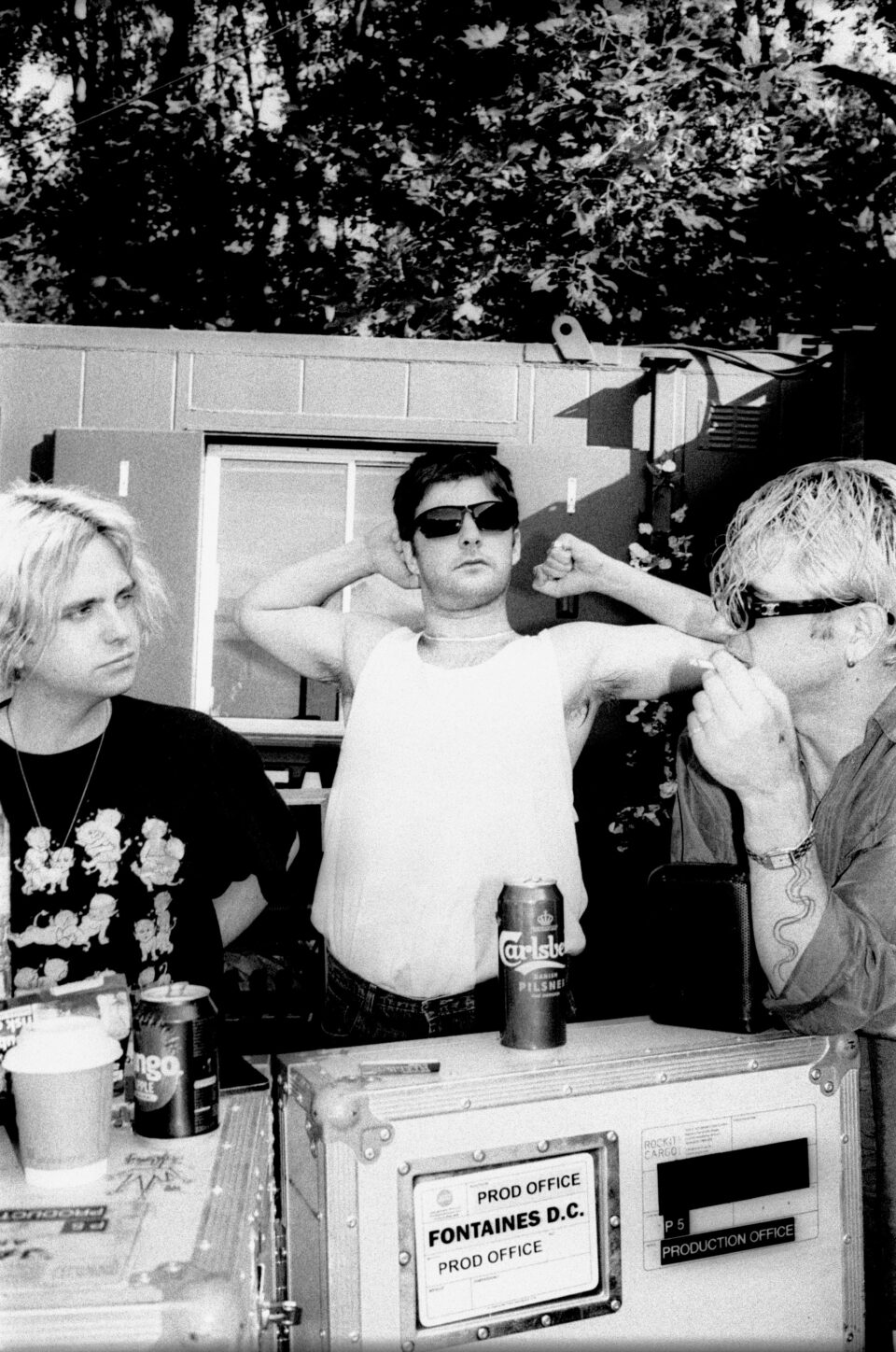

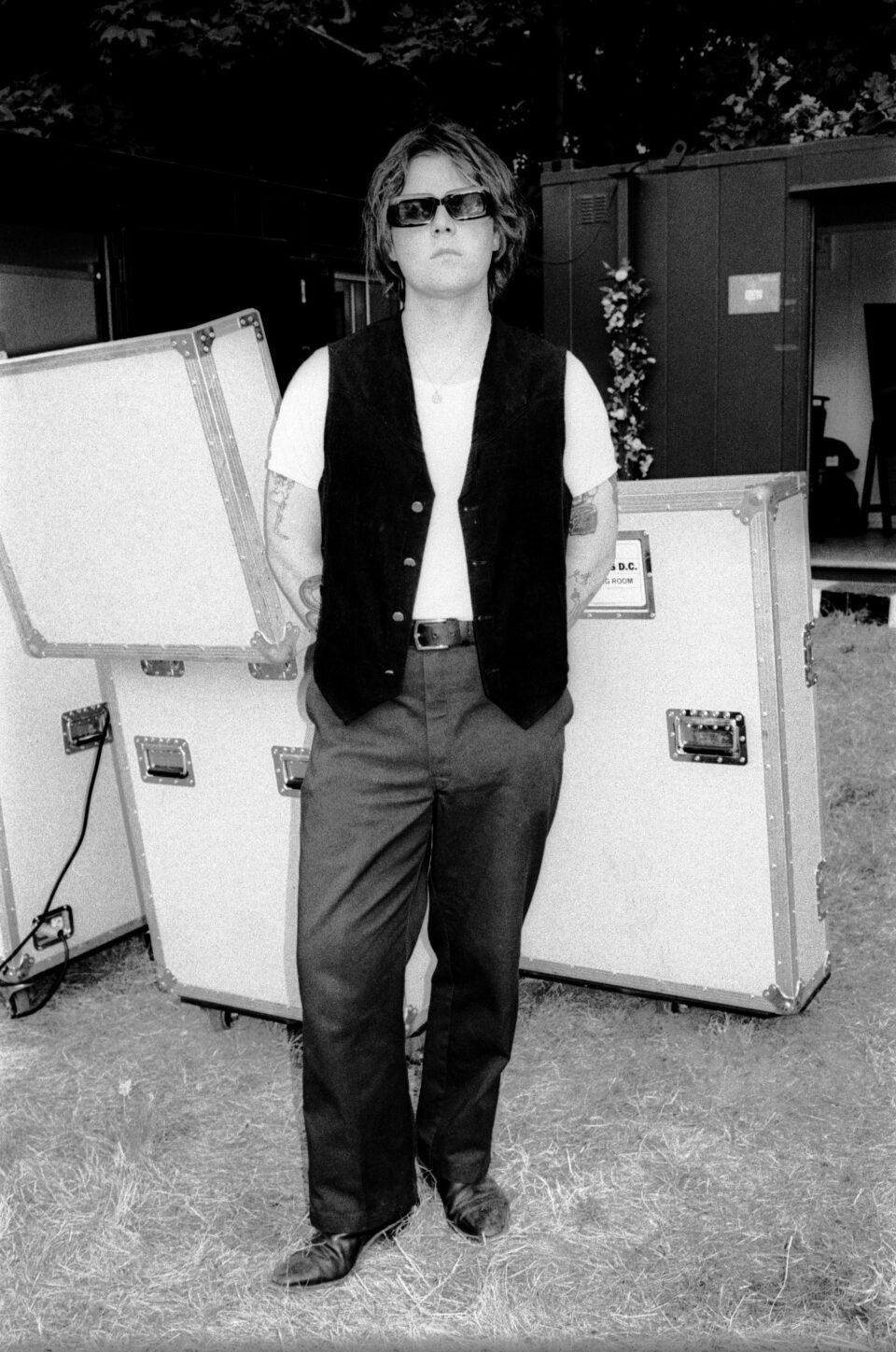

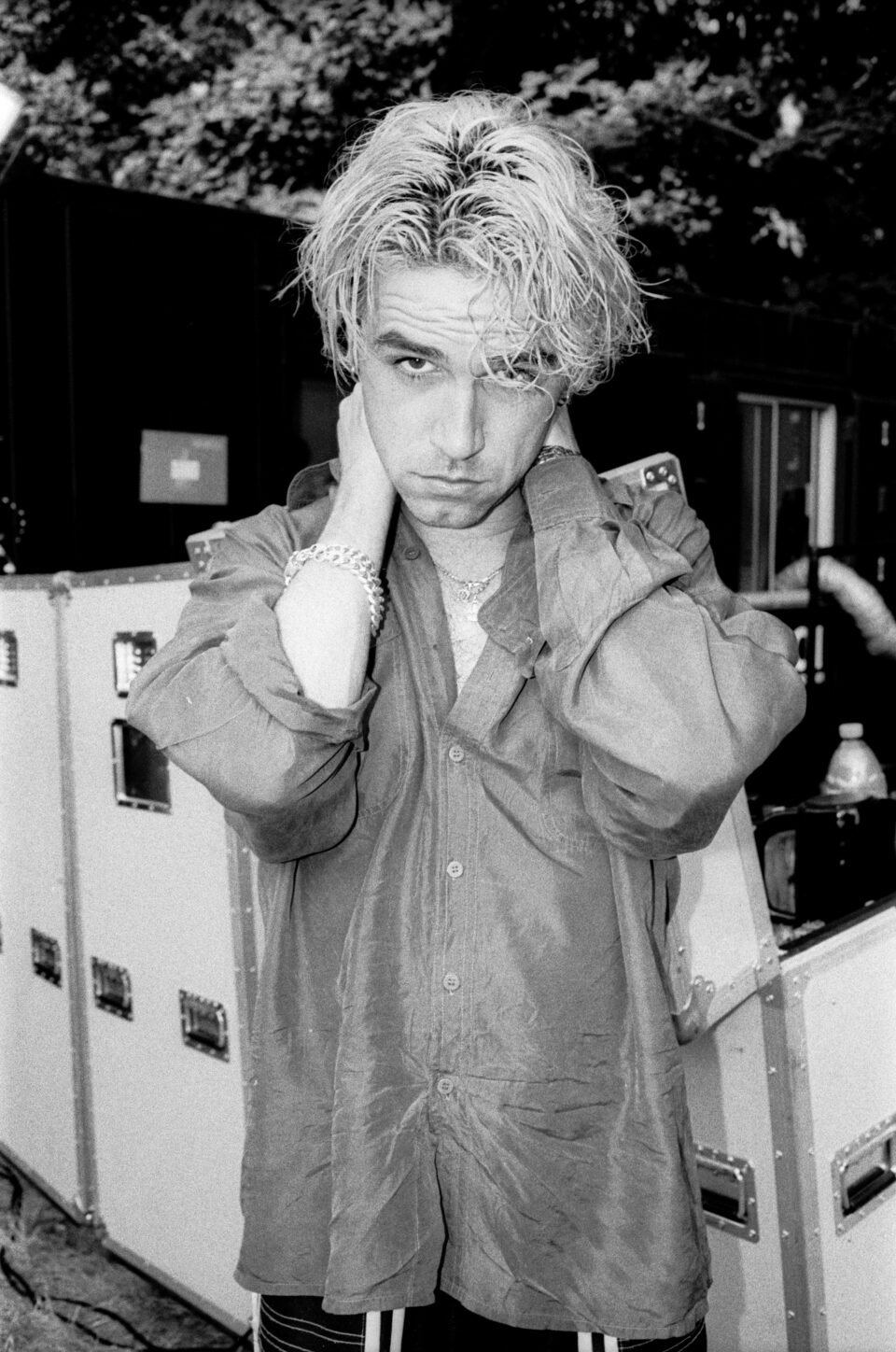

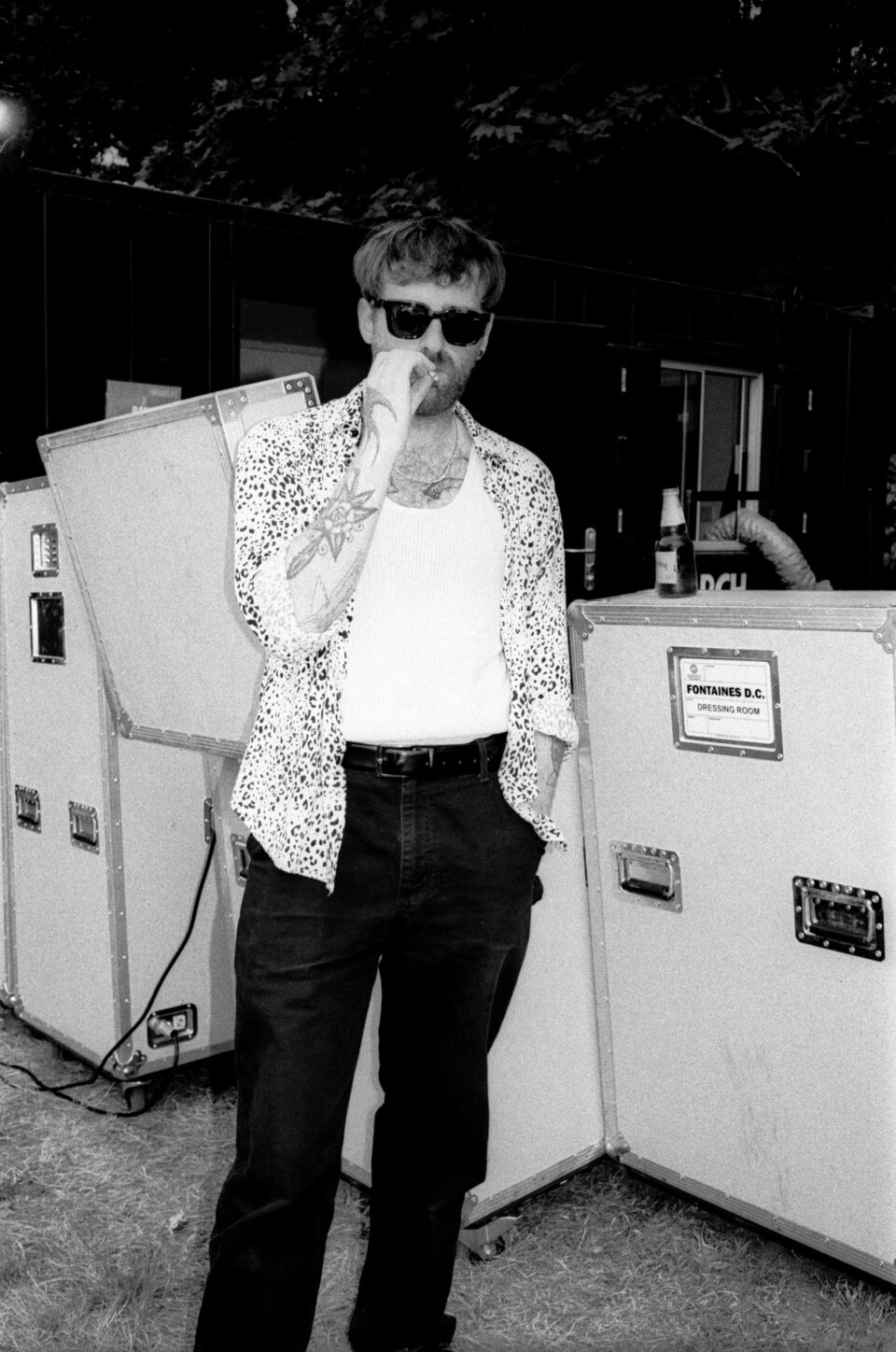

Comprised of frontman Grian Chatten, guitarists Carlos O’Connell and Conor Curley, bassist Conor Deegan III, and drummer Tom Coll, the way Fontaines have skyrocketed from a beloved Irish band to a full-blown, worldwide presence on festival cards and album charts has been eclipsic. Chatten is like a new-millennium Ian Curtis but with a wider range. His stare, as piercing and soul-occupying as the Joy Division vocalist’s once was, complements a polished staccato that flutters with a baritenor’s shape-shifting precision. All the while his backing band has never sounded more precise, empowered, and limitless.

Skinty Fia finds a once-budding rock band fully blossomed into their own. After transplanting themselves to London two years ago, the quintet started feeling the effects of the diaspora and made a record about it. “Skinty fia” is an archaic expression bordering on an inside joke that roughly translates to “the damnation of the deer.” Fontaines are the deer, and the locals everywhere else are the damners. But even though songs like “Jackie Down the Line,” “Roman Holiday,” and “The Couple Across the Way” are soaring accomplishments in a short discography already full of them, Skinty Fia immediately revealed just how much the guys miss Dublin, how they dream of their home amid all of the cultural and generational decay they see wherever they go. Those homesick riffs land swimmingly all across the world, despite the anti-Irish rubbish oozing from the UK.

“We worked ourselves to the bone. We were just totally losing our minds. We won’t let that happen again, because we’ve been able to put our feet down in terms of what our schedule looks like. But we also know how to remain in love with it better than ever now.”

—Grian Chatten

As the band enters their second leg of headlining shows for Skinty Fia, they understand their own limitations with performing a little better. In the Dogrel era, they often found themselves playing two shows a day—playing in-store sets mere hours before taking center stage someplace else. “We worked ourselves to the bone. We’d play a show in Brighton and drive to Bristol and play another show that evening. We were just totally losing our minds,” Chatten says. “We won’t let that happen again, because we’ve been able to put our feet down in terms of what our schedule looks like. But we also know how to remain in love with it better than ever now.”

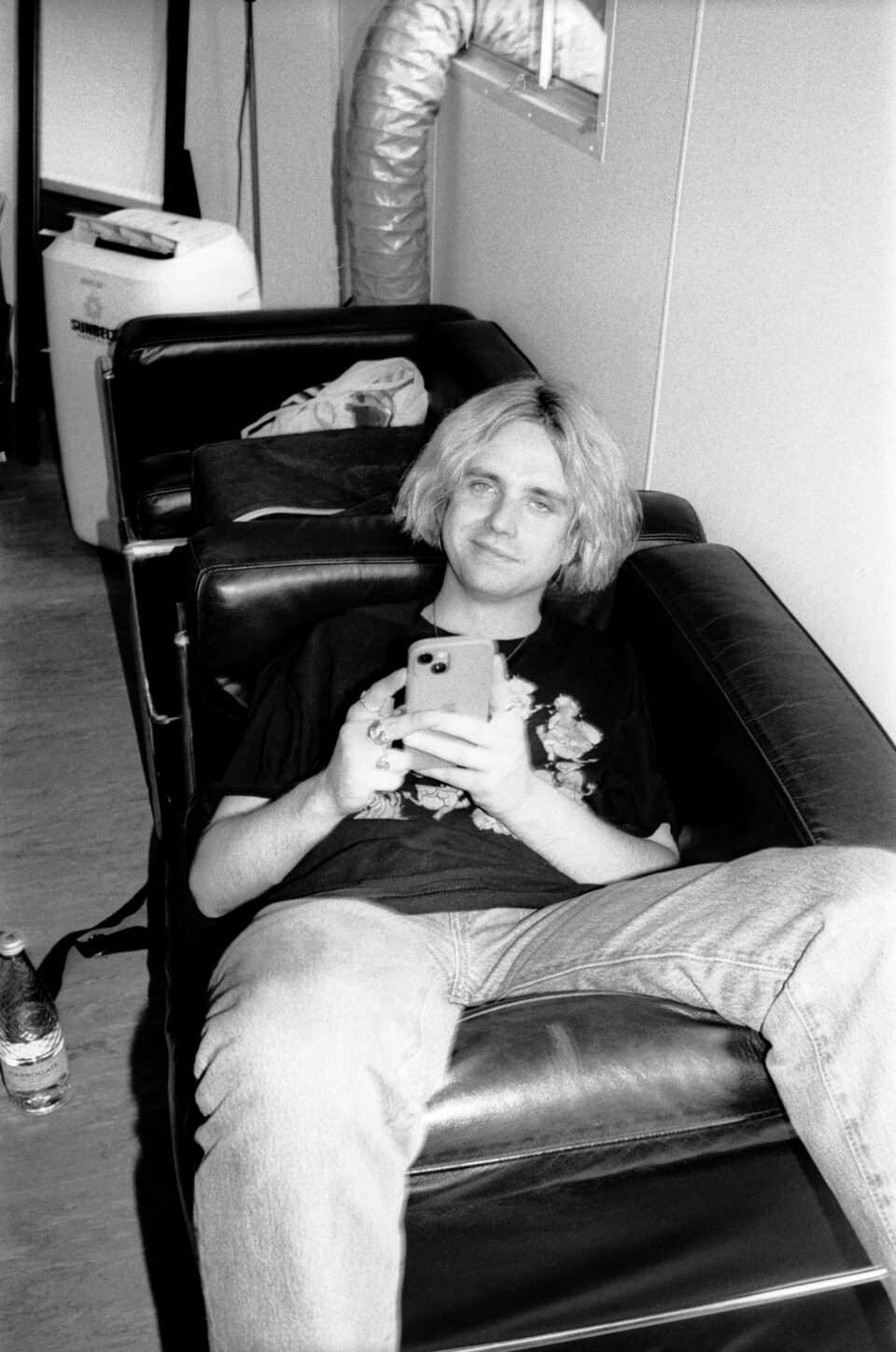

Fontaines never got a chance to tour for A Hero’s Death in 2020, so they’re making up for lost time, which sometimes means having days where they do two shows again, or pulling weeks with five or six shows in as many days. When talking to Chatten and Curley, you can tell they’re having the time of their lives ambling across Europe and the States, but are still wringing out the kinks of such an expansive touring itinerary. “[A Hero’s Death] never really got its day out in the sun because of COVID,” Curley tells me. “We never really learned how to play it, we never got it road ready. So it was two bodies of work that had to go through that development, into a live setting, which is honestly one of my favorite parts of being in this band.”

But approaching a tour with two new, unperformed albums has proved more than worthwhile for the band. They have a wider catalog to draw from, and there’s an excitement about the dynamic potential each track has when it’s properly articulated on-stage. “It’s such an incredible curve to make something in the studio and you can start to let go of the idea of it just being the five of us,” Curley says. “Obviously you don’t want to limit yourself too much and end up doing things that might not be possible live. Then you have to figure out this kind of translation that ends up being something else, and I think you learn something in the process of that.”

“Our live set now, with the dynamic type of sound that we have, it’s quite an ever-expanding snake that goes in both directions even further, rather than as narrow as it started with our first record.”

—Conor Curley

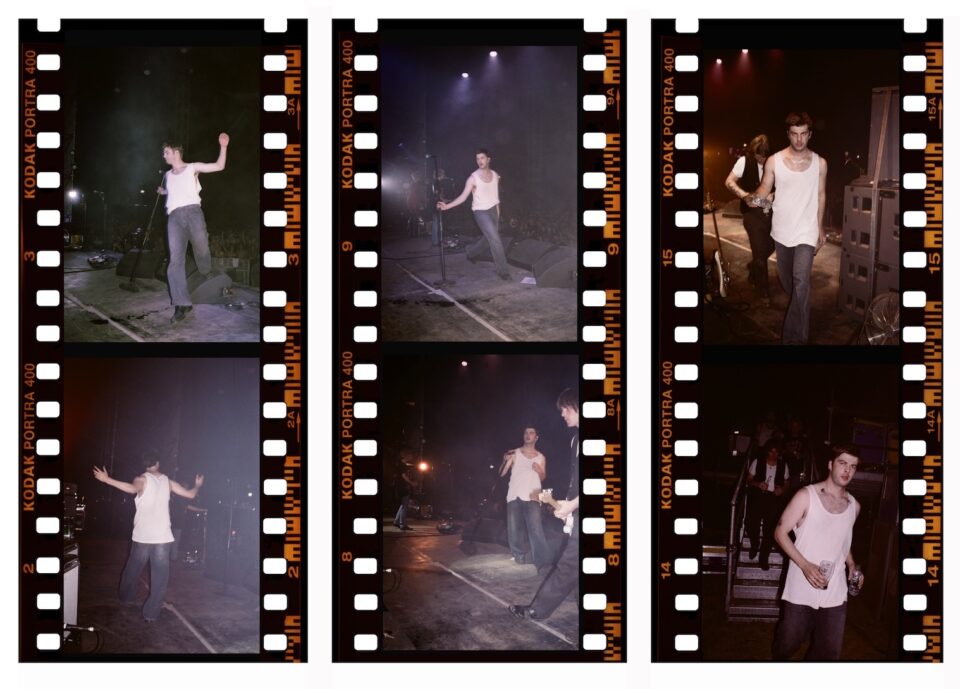

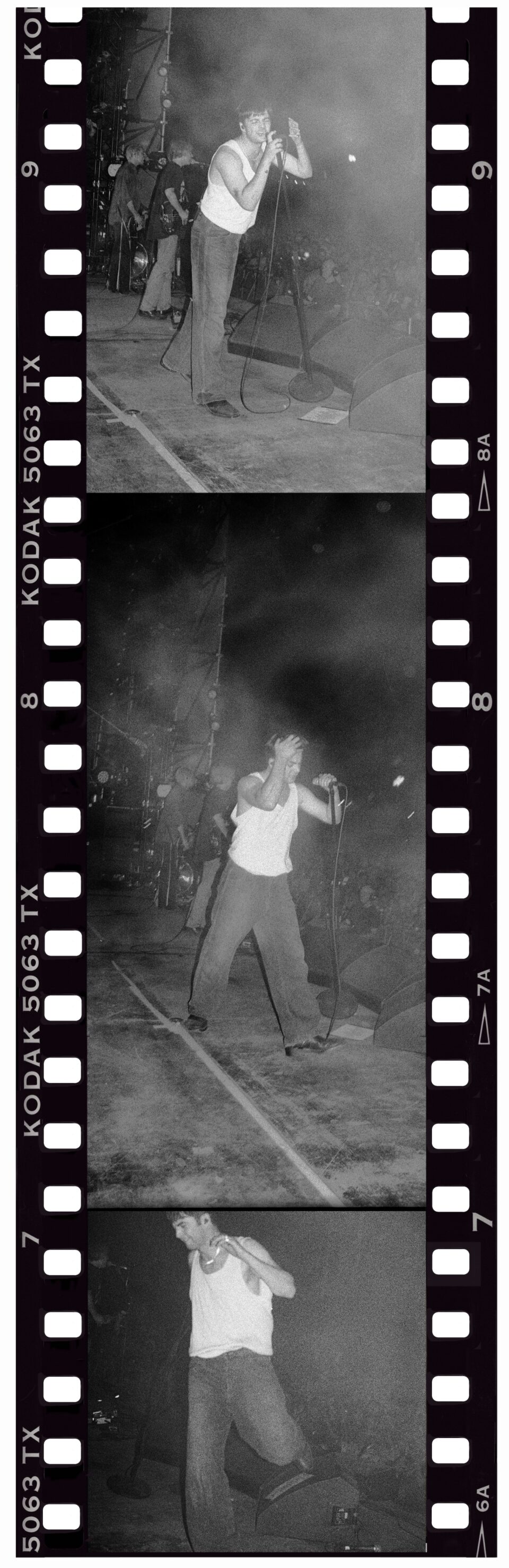

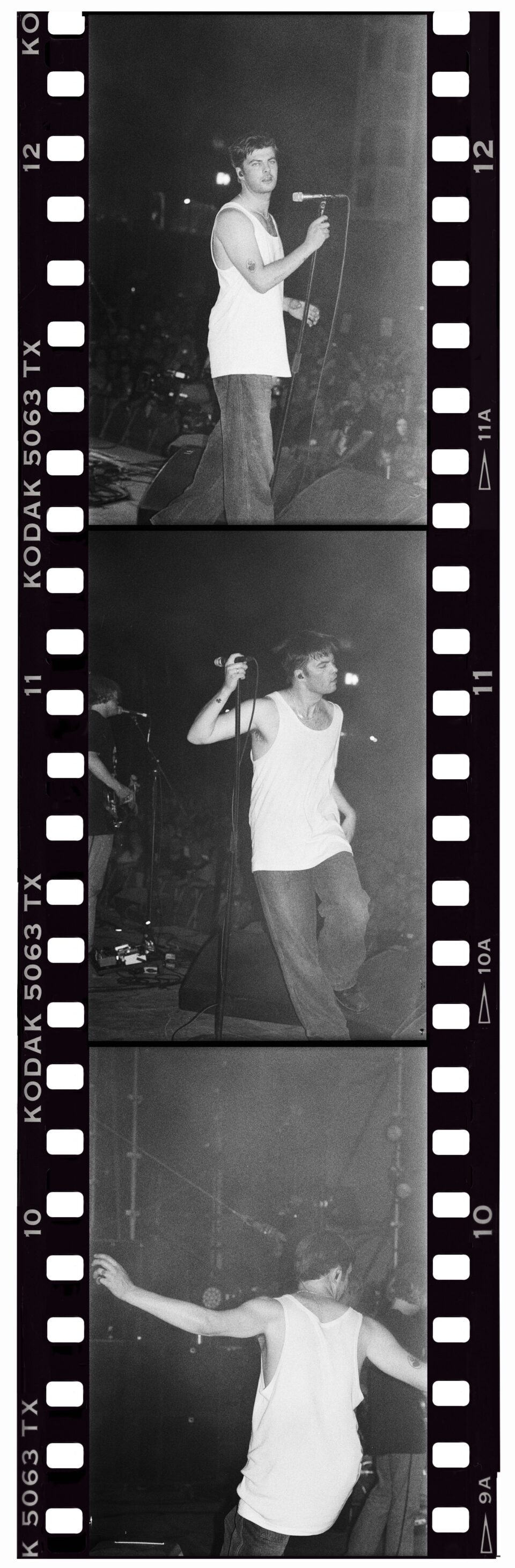

A Fontaines D.C. show can start two ways: Either it opens slowly, by going down a rabbit hole of sounds, or with a startling amount of energy. In both instances, every moment holds the possibility of burning away and then reigniting. “Our live set now, with the dynamic type of sound that we have, it’s quite an ever-expanding snake [that] goes [in] both directions even further, [rather than] as narrow as it started with our first record,” Curley says. The mix of slow songs and magnetic crowd-shakers offers a seismic binary for performances, an opportunity to strike a balance that flashes the band’s compositional firepower. “You can really get a sense of the degrees of emotion that are in each of those whenever they’re pinned together,” Curley adds. “It’s a lot of intensity, and I think that’s something we’re always going to have. But I think we’re starting to rely on the music more than the showmanship quality of being in a rock and roll band.”

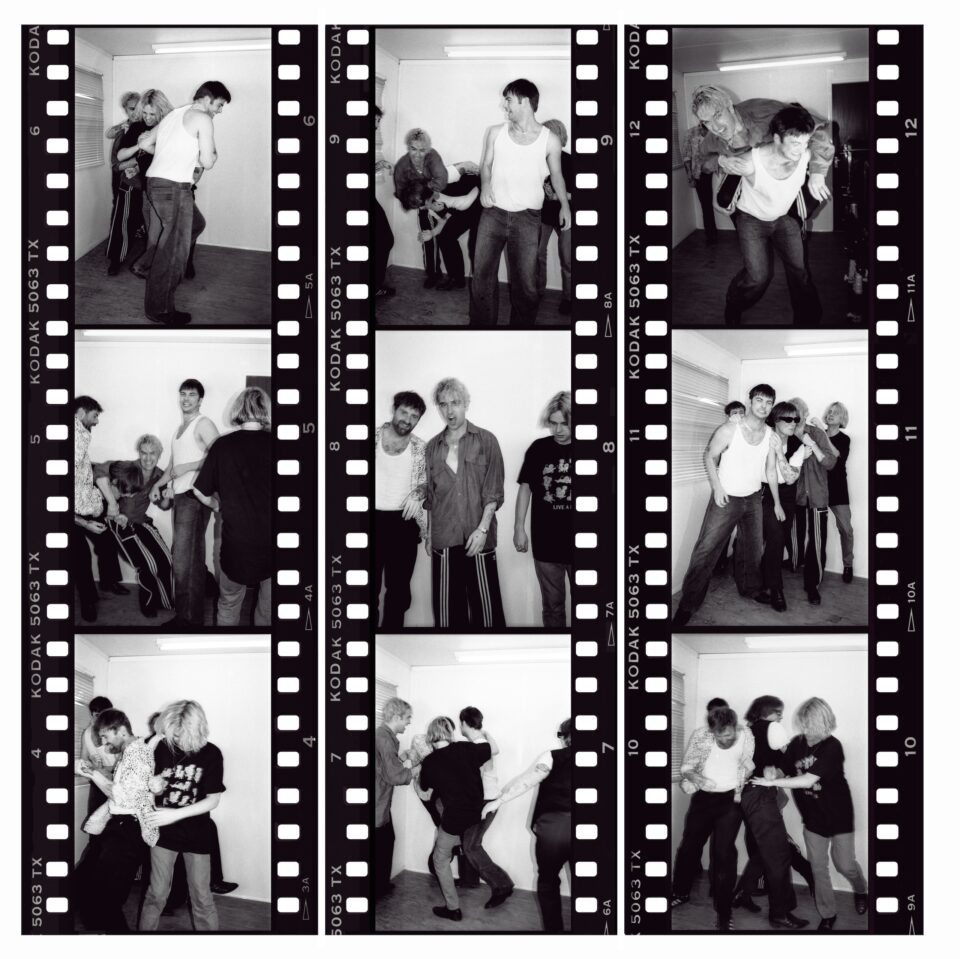

That showmanship has always been there. Fontaines have a live persona that’s a heightened and harnessed version of what we hear on their records. When they were younger and playing smaller shows, they tailored their setlists around what they could fit into a box. One night, they’d lean into the punky, fast paces of “Hurricane Laughter” and “Too Real”; other times they’d glean softness by playing around with the balladry of “Roy’s Tune” and “Dublin City Sky.” “We tried to go out there and capture people’s imagination and what those songs can make you feel by portraying them, physically, ourselves,” Curley says. “It was an amazing way to play for a while, but in some ways, it’s not really that sustainable before it becomes a little bit contrived.”

That evolution of the band’s live set goes hand-in-hand with their strengthened songwriting. The parts of themselves that arrive on tape are now arriving on-stage. When the intoxicating charisma enriches a new stage in a new city every night, then you’ve finally broken free. “You write a song and you feel your imagination set sail and you see yourself as this person with this particular confidence or swagger or power,” Chatten says. “It remains, to some extent, as just a thought or a dream or an imagining. Then, when you start performing those tracks, you start to inhabit that person. It’s not like you’re playing a role, you’re simply just liberating an aspect of yourself that you’ve drawn out with songwriting.”

“You write a song and you see yourself as this person with this particular confidence or swagger or power. Then, when you start performing those tracks, you start to inhabit that person.”

— Grian Chatten

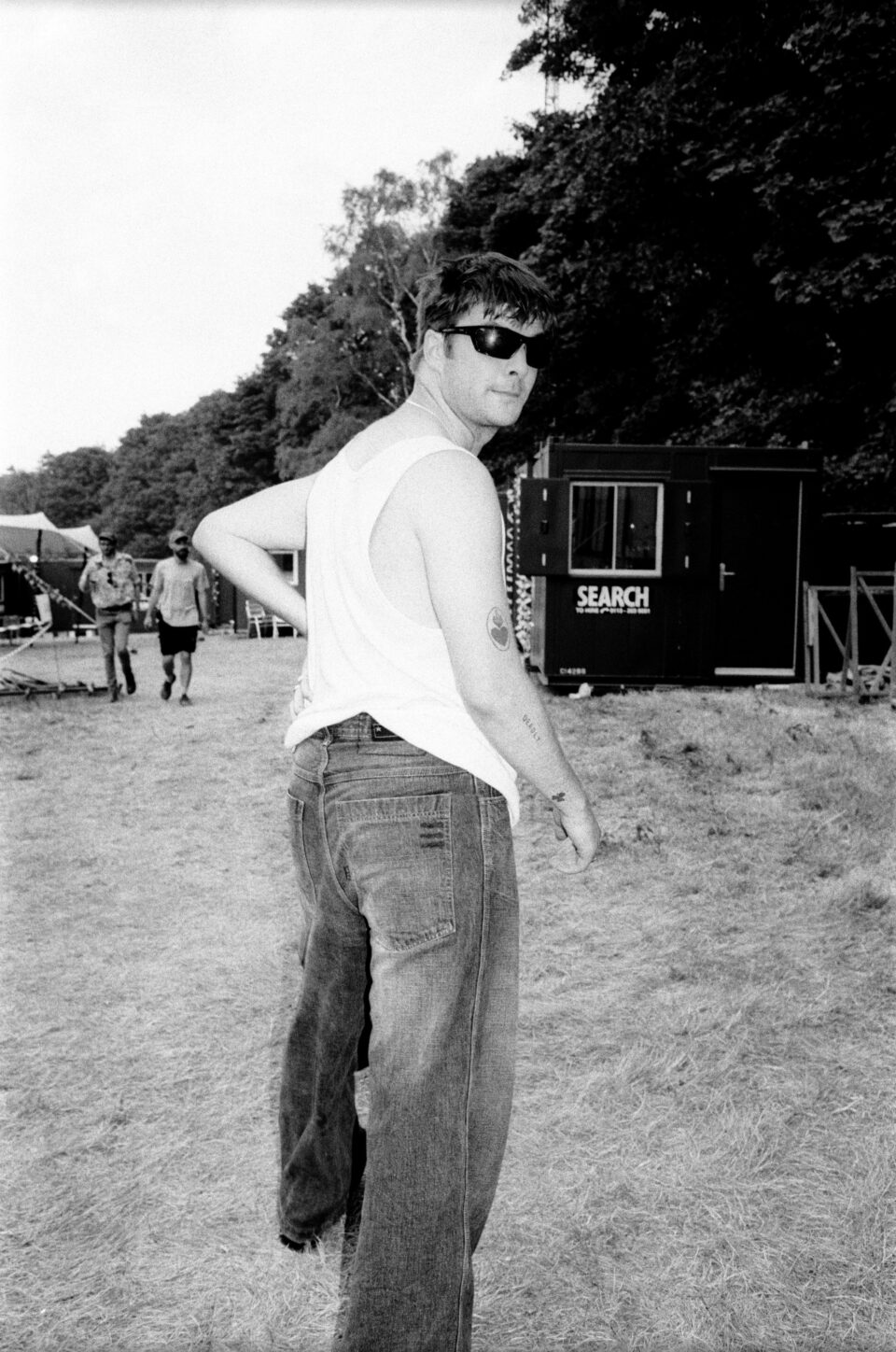

This summer, those liberated parts of the band have taken new shapes at festivals across the world. Since finishing the first American leg of the Skinty Fia tour in May, they’ve taken turns at Finland’s Flow Festival, Sweden’s Way Out West, Glastonbury in England, Best Kept Secret in the Netherlands, and Primavera Sound in Barcelona, among others. Their set at Latitude Festival in England was the last in a run of 80 shows. “We were trying to ignore the fact that it was the last one,” Chatten says. “It was, ‘Let’s let our legs crumble beneath us. Let’s just fucking enjoy this. Let’s have a few cans and just be at the festival.’ And it was incredible. It was a really, really good show.” At Primavera two months prior, the band ended up in the mid-evening mainstage slot on Sunday and. “That was probably the best show we’ve done,” Curley adds.

Chatten is trying to employ that mantra more often in the band’s sets. Rather than playing a show and moving on to the next one, he’s savoring the moments and embracing the community that comes with the festival circuit. “You try to move off the back of the momentum. If you get a run of three or four shows, you can go into any festival feeling like it’s going to go well,” he says. “Then you can just enjoy it. That’s why what I’m trying to do now is really perform for my own enjoyment. I don’t necessarily know how long this is going to last. Hopefully it lasts for a long time, but while we’re doing it I’m trying to get better at taking it in.”

For Curley, he understands that not everyone at a festival is there to see Fontaines D.C., specifically. “You’re going out there to try and convince people that when we do come back and play our own show, and it’s on our own terms, that it will be a worthwhile thing to do,” he says. Beyond going out and putting on a memorable set, there’s a strong sense of community involved in festivals, and it’s something the band sees from all angles. “Everyone’s supporting each other,” Curley adds. “I see it even more deeply with the working crew. Whenever you see people loading in, you see different guitar techs and a different backline crew. You haven’t seen each other in years, [but] you used to work with each other in different bands. It really warms my heart when I see that stuff, because it really makes you feel like you’re a part of a bigger thing.”

When Primavera Sound comes to Los Angeles in September, the band will be in the Saturday night lineup alongside Nine Inch Nails, Low, and Kim Gordon. Chatten cheekily proclaims that the quintet will probably be “the palest people in California” when the time comes to put the spotlight on Skinty Fia at State Historic Park. Every time the band comes to America, the “feeling of starting over” arrives in tow, according to Curley. Their first tour in the States was with IDLES, another festival mainstay who’ve cultivated a grandiose, energetic, and unparalleled stage presence of their own. “To be on a card with them did us a lot of good,” Curley says. “People could expect this intense kind of show and songs that had a lot of emotion and [are] political and leaning toward something that can make you think about things differently.”

“One thing about our songs is that they’re never trying to point the finger about how to feel about things, but trying to engage people to look at things around them and feel injustices that they don’t agree with, in terms of their existence.”

—Conor Curley

Though Fontaines D.C. often sing about the disparities of their home country, the message often rings familiar in the United States. Curley equates the disappearing cultural autonomy for people in Ireland to the anti-abortion laws reaching across America right now. “The idea of one religious moral code or ideology seeping into the federal government is a very scary prospect for young people,” he says. “One thing about our songs is that they’re never trying to point the finger about how to feel about things, but trying to engage people to look at things around them and feel injustices that they don’t agree with, in terms of their existence.”

In July, the band played two nights at Iveagh Gardens Festival, their first shows in Dublin in a long time. In Chatten’s own words, they were the most important-feeling shows they’ve ever played. “Dublin is changing as rapidly as any other part of the world,” he says. “It’s losing its culture there and really important places have been ripped down and replaced with hotels. It’s a bad place to be a young person, particularly a young, creative person. It’s a bad place to aspire to live in and to buy a house in.”

At those gigs, the deteriorating tides in Ireland were no longer unspoken. Skinty Fia was a testimony bringing that cultural decay to the mainstream. In turn, the audience’s energy was like a pressure cooker, and the environment was unprecedented for the guys. “All of these problems have been surfacing and becoming more widely known over the last couple years in Dublin,” Chatten adds. “We know it, and I think the crowd knew that we knew it. So there was just this common understanding and it was really cathartic. It was cathartic to the point of scary for me, to be honest, when we first came out on stage, [because of] the amount of political and emotional energy that I felt from it.”

Everything about Fontaines is inherently Irish, but the way their home country’s government treats its people feels universally resonant. In countries across the globe, people are having their autonomy and their futures stipped away. And that theft is largely ignored by those who are privileged enough to not have their head in the guillotine. “That denial is one that could even generate generational trauma to people who really wanted to do something new and create something,” Curley says. When the band plays in Dublin, they see their peers scraping and clawing just as they did, and see how some of them can’t move someplace else and start anew. “That’s part of the real emotion when we play there,” he adds.

In YouTube comment sections, people from Brazil or Mexico praise the songs and share their story about how they connected with the messages as they endure similar circumstances in their own countries. “I really did believe in this idea that the language of music, when you’re really trying to share an emotion that you have, is one of the best mediums to do that,” Curley says. Though the average Joe in Mexico City might not have his back up against the wall in the specific way a Dubliner does, the end goal is the same: to achieve some kind of liberation that ensures opportunity for the population. “I have faith that people will be able to relate to and understand whatever kind of plight we might sing about,” Chatten adds. “To me, it’s interesting cross-cultural pollination, and I’ve never felt like I’m singing into the void. I always feel like there’s a message received from the other side of the world.”

“I have faith that people will be able to relate to and understand whatever kind of plight we might sing about... I’ve never felt like I’m singing into the void. I always feel like there’s a message received from the other side of the world.”

—Grian Chatten

Compared to Skinty Fia, Dogrel was much more poetic, especially in how the record paints vivid portraits of the Dublin that the band grew up with. The album was not a revolutionary manifesto on how to fix the systemic clusterfuck going on in the city’s government. Rather, it was a scene-setter. The band’s foot was not yet on the gas like it is now. Because they’re confident in who they are and who they’ve got in their corner, the songs can unravel in a much more organic way. “When it’s your first record, that’s when people are going to judge whether or not they like you. You have to make a good impression live, really,” Chatten says. “I think [A Hero’s Journey] was really written to chill us out and give us a place to go, mentally, on tour. It was a refuge for us. Then I think, strangely enough, because it was written largely during COVID, no gigs happened. I think [Skinty Fia] was written from our point of desire for community and for celebration.”

The songs on Skinty Fia brim with unabashed Irishness and reckon with the band’s own worries for the future of their country, whether from far away or in the middle of the muck. When Chatten sings about feeling guilty over leaving Ireland on “I Love You,” it’s a familiar gesture that can be tapped into by anyone who fears they might have to leave their home in order to live better. It’s true that to love a place, you must first speak widely and honestly of its greatest faults. But you can still hope it gets better, even if you no longer live there. That place will always be a part of you, no matter where you go. The beautiful part about a song that tells the story of millions of people is that someone, somewhere—anywhere—can plug themselves into it and, for a few minutes, feel like their voice is also being heard.

And as Fontaines D.C. bounce from stage to stage across the world delivering sermons on the strifes in Dublin, their wholehearted message is one of universal truth enduring far beyond geographical boundaries. FL