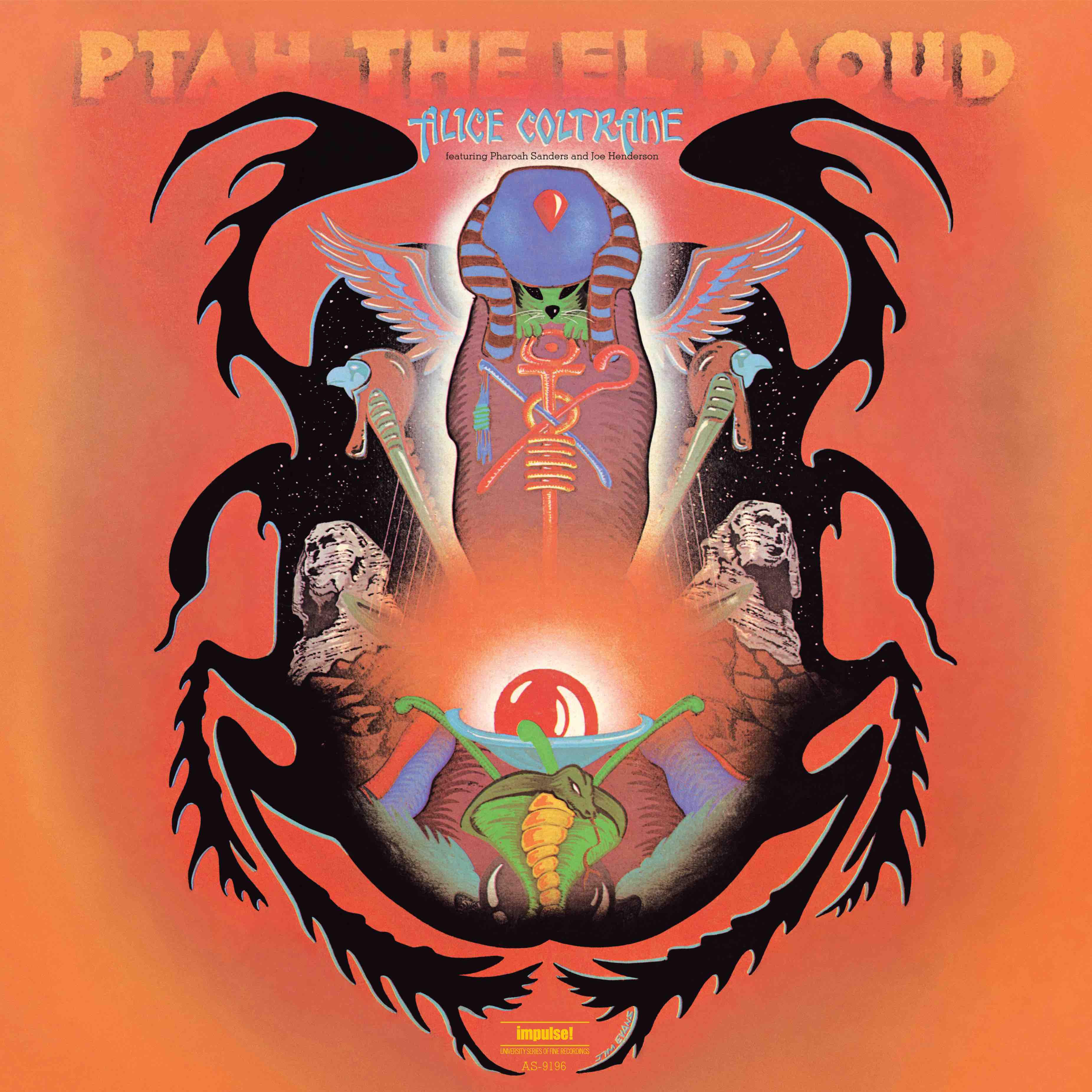

Alice Coltrane

Ptah, the El Daoud

VERVE/THIRD MAN

The further we delve into the work of Alice Coltrane, the more impressionistic and onion-like the composer, pianist, and harpist reveals herself to be, with skin and layers peeling and blossoming anew with every spin. Originally issued by Impulse! in 1970, its latest repressing is part of a new deal between Verve and Third Man’s vinyl stable that means that Ptah, the El Daoud now comes in sturdy, high-grade, yellowy-gold material to reflect Coltrane’s sunburst spirituality.

Beyond its coloring, and following the 1967 death of John Coltrane, you can hear their intertwined and holy path, their mission, in the cosmic music. You can sense Alice Coltrane’s growing confidence in relaying that path—both as a composer of potently purposeful and hypnotic music (such as the title tune’s ode to the beloved Egyptian God, Ptah) as well as a band leader, directing as she does two of jazz’s most renowned tenor saxophonist/alto flutists Pharoah Sanders and Joe Henderson through her higher states of consciousness (celebrated bassist Ron Carter and drummer Ben Riley, too, were part of Coltrane’s ensemble for this recording).

Tied to the era of post-psychedelia and transformational, mystical music, every spaciously displayed moment of Ptah is a rare jewel, from the cathartic humming of the 14-minute title track through to the album’s final grace notes of “Mantra,” with Sanders and Henderson cojoining and spinning outward into the universe every step of the way. As the tenor men drift, Coltrane adds an emotional, sinewy, and askew piano line—an exclamation of pain in the center of such melodic beauty—that lends “Mantra” something of a bittersweet tonal epiphany. The same can be said of the majestically melancholy blues of Coltrane’s piano break on “Turiya & Ramakrishna,” backed primarily by Riley’s brushed drums, Sanders’ bells, and Carter’s own effusive solo.

By the time you get to “Blue Nile,” with Coltrane’s harp acting as a summer rain through the cumulus gray-blue clouds of dueling flutes from Sanders and Henderson, it becomes evident that this is the very height and definition of free, clear, God-seeking jazz.