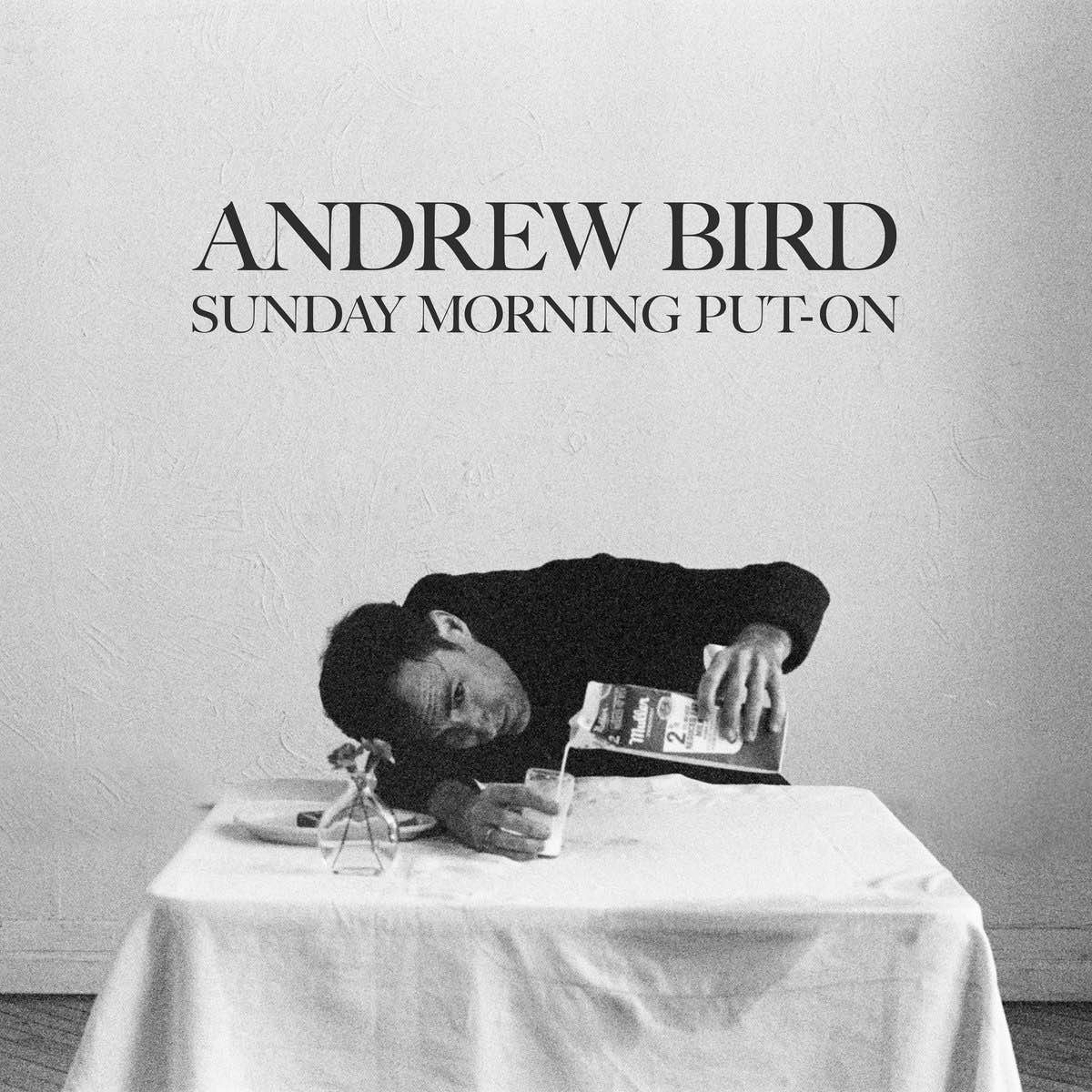

Andrew Bird

Sunday Morning Put-On

LOMA VISTA

There’s always been something classic about Andrew Bird’s music. There were the pre-war jazz/swing-inspired compositions of his early days leading his band Bowl of Fire, which followed on directly from his involvement with Chapel Hill’s jazz revivalists Squirrel Nut Zippers. His solo records after disbanding that outfit toned down the jazz elements and veered instead into something more grandiloquent, refined, and sophisticated—classically trained pop songs infused with eccentric experimentation courtesy of his whistling and violin (which he plucks and plays like a guitar in addition to using it in the more traditional method), both of which assumed a more central role in his increasingly idiosyncratic compositions.

Along the way, Bird’s reputation as an intellectual and cerebral songwriter—perhaps a musician’s musician’s musician—grew in tandem with his profile. Though his music has always felt too intelligent for true mainstream success, he nevertheless broke into its fringes, and 2012’s Break It Yourself even hit the #10 spot on the Billboard 200. Yet his new collection Sunday Morning Put-On is a return to his jazzy roots. On it, Bird’s trio—rounded out by Ted Poor on drums and Alan Hampton on bass, with additional guitar and piano from Jeff Parker and Larry Goldings—revisits classic jazz songs by the likes of Cole Porter, Duke Ellington, Rodgers and Hart, and more. At face value, it’s more accessible and less erudite than much of his solo work, but these are far from mundane Connick Jr.–esque reinterpretations.

Take “I Fall in Love Too Easily,” a 1944 jazz standard popularized by Frank Sinatra and, later, Chet Baker. The interpretation here retains the soul of those versions, but also infuses it with Bird’s trademark insouciance and peculiarity, in no small part thanks to his violin playing and whistling. His vocals throughout this album recall those of Baker, as it happens—mild and plaintive and restrained, albeit without the drug-addled tragedy that defined (and probably inspired) Baker’s sorrowful timbre. Still, “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” “I Cover the Waterfront,” and “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face” are all executed with his trademark precision, poise, and, at times, quirkiness.

If anything, these songs are almost too close to the originals to truly flourish in typical Birdian style, but that’s a minor quibble. This album is still a perfect combination of respect and reinvention, and another string to Andrew Bird’s truly magnificent and inimitable bow.