Going into February 28’s Golden Globes ceremony and next week’s nominations for the 2021 Academy Awards means a frank discussion of an even franker film: director, co-producer, and co-screenwriter Shaka King’s Judas and the Black Messiah.

Now streaming on HBO Max, King’s new film with producer Ryan Coogler and co-author Will Berson is a subtly told (yet no less incendiary for its quietude) historical drama on the life, activism, and death of Illinois Black Panther Party Chairman Fred Hampton. The “Chairman,” just 21 when he was assassinated by the police and affiliates of the FBI (under J. Edgar Hoover’s directives), was an eloquent, poetic pontificator and educator who made it clear that the only way for true equity between white America and Black America was through revolution. Sometimes that revolution would be televised. Often that revolution would be bloody. Always would that revolution be necessary—and led by the feeding of the mind, the body, and the soul.

Where King and co-screenwriter Berson’s film derives its holy name is from the true life tale of petty Chicago criminal William “Bill” O’Neal getting arrested stealing a car while posing as a federal officer, only to be approached by FBI special agents in order to infiltrate the Black Panthers and get close to Hampton and his closest affiliates. That O’Neal got within skin’s distance of Hampton—an integral cog in the daily workings of the BPP and Hampton’s family, becoming a necessary part of the Panthers’ organization and its moves toward community outreach (BPP’s Free Breakfast for Children Program) and the creation of the multiracial Rainbow Coalition—only to give the Chairman up in his sleep makes him a betrayer of the worst sort. Judas.

Hampton had to die for his so-called sins, had to be “neutralized,” in Hoover’s words, as the FBI chieftain did not want him to remain in prison where he’d be hailed as a hero (like Oakland’s Black Power political organization founders Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton, or Eldridge Cleaver who went on the run and became a celebrated author). While King’s already-haunting film closes with the real life Hampton speaking out in one of his most fiery speeches in rare archival footage, O’Neal is revealed as having continued to work within the Panthers, as a paid informant, before committing suicide.

During a February virtual press summit for the film with Daniel Kaluuya (who portrays Chairman Hampton) and Fred Hampton Jr., the current leader of the Black Panther Cubs (born just weeks after his father’s assassination), the two talked about how real and rare an opportunity it was to craft any sort of discussion about Hampton—a beloved figure in Black history of whom little is still widely known. Until this film’s debut.

“I took in the scope, ideas, and concepts of his ideas, who he was, and his love for the people,” said Kaluuya. “It’s continuing a legacy, through this medium, that Fred Jr. is continuing in real life… The power of loving those who look like you and those in your own community; that resonated with me. Chairman Fred had his own internal revolution. He was free within his own spirit, mind, and soul. He wanted to give people the tools to be free within themselves, to free themselves—that meant education, that meant food, that meant legal aid; his strategies to promote internal liberation and community unity.”

Paraphrasing from one of his own poems dedicated to his father, Hampton Jr. said of the Black Panther activist, “I learned lessons from your legend of what a man is supposed to be. Our streets are our office. Our office hours are 24/7.”

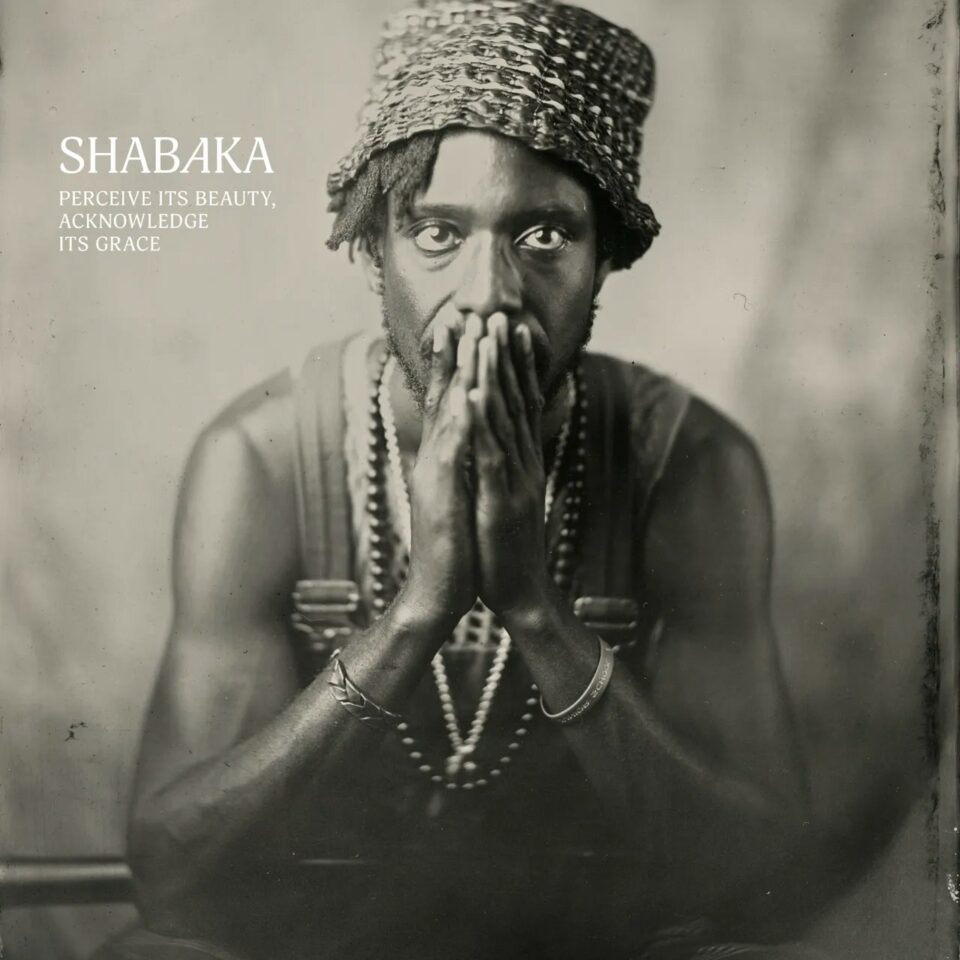

Talking to Hampton Jr.’s poetry, and knowing that information on the real Hampton is rare, his story untold, and that his real life’s impact has yet to be truly examined beyond the films’ still semi- fictitious narrative, Shaka King spoke with several present-day fellow activists and pastors about why Judas was a must-film story, as well as the inspiration behind getting involved with the production in the first place.

“For me, the thing was his words,” said the director/co-writer. “His words were incredibly profound, always relevant—and he was able to take concepts that academics have always made sound more complicated, more complex, into plain English. He was a very relatable person, yet he was superhuman. He put forth ideas and ideologies that—normally—you’d have problems getting through the Hollywood bureaucracy.”

A spoonful of sugar later (or “the pill in the applesauce”), and King and Berson’s script for Judas was a go, one that, in the director’s words, merged the best of the ideas behind a biopic format and the undercover movie format with a love story featuring Hampton’s wife, and an ensemble cast’s story (the additionally important crew of BPP associates and activists). Also told in depth is the story of O’Neal—“a cipher,” in King’s words—living a lie between worlds, between working for both the FBI and the BPP. “O’Neal was constantly shifting and shapeshifting without knowing exactly who he was.” You can’t have a Black Messiah without a Judas. FL