More than just telling a story, songwriters create the sonic cocoon in which a narrative unfolds. They supply the atmosphere, the characters, themes, plots—as do novelists. Alternative music—whether through art rock’s enigma, folk’s delicacy, or punk’s immediacy—can be a vehicle for prose, a way to understand our own and other people’s lives, reach catharsis, address injustice, or escape modern life altogether.

There are artists who embrace their literary proclivities to such a degree as to rewrite existing passages of fiction—whether it’s novels or short stories, from Emily Brontë to J.D. Salinger to 19th-century Austrian intellectuals. On some of the proceeding tracks, the luminary literature informs every lyric, direct quotes are lifted from books, characters are cited by name. On others, the mood of a book or the topic it confronts is the primary inspiration—a bittersweet winter farewell, a love triangle, or simply a memorable visual.

These artists have in common a willingness to let their pen lead their plectrum. Across indie pop, art rock, emo, punk, folk, and any other left-of-center subgenre in-between, these are some of the best tracks inspired by literary fiction.

Japanese Breakfast, “Be Sweet”

Crowning 2021’s year-end lists, “Be Sweet” is the lead single from Jubilee, Japanese Breakfast’s jubilant opus. Michelle Zauner co-wrote the song with Wild Nothing’s Jack Tatum, and it’s their take on gleeful funk pop—a roller disco-ready bop that calls to mind glitter balls and flashing lights, heads turning as an elegant maven slices across the rink. The song’s inspiration was darker than the imagery it evokes; namely Raymond Carver’s short story “Tell the Women We’re Going” from his 1981 collection What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Carver’s taciturn prose follows two lifelong friends who, now married with children, attempt to court two women outside a rec center. After being rebuffed, one of the men is infuriated and attacks and kills the women. Aside from providing her own, glossier brand of dirty realism, Zauner turns the story’s title on its head, opening “Be Sweet” with the line, “Tell the men I’m coming,” before requesting sweet treatment from an offending partner.

Death Cab for Cutie, “Cath…”

Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights has provided inspiration for an above-average share of music. Kate Bush’s eponymous baroque pop masterpiece is the most notable, but there’s an underdog in Death Cab for Cutie’s “Cath…,” which modernizes the struggles of the central protagonist over crispy guitars and syncopated drum thrums. “Cath, it seems / That you live in someone else’s dream,” Ben Gibbard sings directly to Catherine Earnshaw, the daughter of the Wuthering Heights estate who marries Edgar despite loving Heathcliff. It’s a testament to the relatability of Brontë’s writing that Gibbard makes Cath sound like a girl who lives around the corner in Bellingham, Washington, someone he used to know. “You closed the door / On so many men / Who would have loved you more.” Societal expectations, wasted love—Death Cab captures the urgency of these topics and Wuthering Heights’s seasonal melancholy with infectious emo-pop euphony.

PJ Harvey, “The River”

Expressing ideas with a restricted number of words is a challenge that songs, poems, and short stories all undertake—and Flannery O’Connor was a master of the latter form. The Queen of Southern Gothic was no stranger to the macabre and ironic. In “The River,” a young boy is taken from his neglectful parents to be baptized by a healer. The healer provides the boy with a sense of belonging, prompting the boy to return the next day only to be swept away by the river’s current to his death. British avant-rocker PJ Harvey re-told this tale on her track of the same name from Is This Desire? A hymnal piano line descends as though following the river downstream while a funereal trumpet coupling and shuffling snare drum recalls a marching band procession. The result is haunting and gothic with arresting visuals: “And the sun sets low / Like the pain in the river.”

Sonic Youth, “The Sprawl”

“The Sprawl” is a driving noise rock din from the early pages of Sonic Youth’s venerable Daydream Nation. The track borrows its title from a trilogy of dystopian sci-fi novels by cyberpunk pioneer William Gibson. Neuromancer, Count Zero, and Mona Lisa Overdrive—the overlooked relatives of Brave New World and 1984—explore the advancement of AI and machine intelligence and are set in a sprawling megapolis that stretches from Boston to Atlanta. This setting is imagined in the song’s expansive outro with Moore and Ranaldo’s interlacing guitars and distant hisses of feedback and distortion. Sci-fi regularly informed the New York group’s writing: the 1987 album Sister was in part inspired by the works of Philip K. Dick, and “Pattern Recognition” from Sonic Nurse nods to Gibson’s 2003 novel of the same name.

Kate Bush, “Flower of the Mountain”

Molly Bloom, a character from James Joyce’s allusive oeuvre Ulysses, provides the lyrics for Kate Bush’s “Flower of the Mountain.” After Joyce’s estate forbade Bush from citing Bloom’s soliloquy on 1989’s “The Sensual World,” she asked again 20 years later, and Joyce Junior finally obliged. “I felt that the original idea had been more interesting. Well, I’m not James Joyce, am I?” Bush said after reworking the song for her Director’s Cut compilation. Retaining—if not intensifying—the sensuality of the original piece, “Flower of the Mountain” is mysterious and intimate, its melody delivered by Irish Uilleann pipes over Bush’s whispering recount of Molly’s bedroom desires. The song isn’t Kate Bush’s most famous literary impartation, but clearly she’s one of the few artists who can be trusted with the most reverential of 20th century literature.

St. Vincent, “Severed Crossed Fingers”

The morbid imagery of severed crossed fingers is taken from short fiction author Lorrie Moore’s Birds of America collection. St. Vincent’s Annie Clark explains in an interview with Mojo that “‘Severed Crossed Fingers’ is a Lorrie Moore reference, from a short story about a woman who reads a story in the newspaper—they’re sifting through a plane crash and find somebody’s severed hand, but the fingers are still crossed, and I thought that was such a great, hilarious, bleak metaphor for life.” Vincent’s valedictory album closer is an epic, joyous synthscape, like delirious laughter, an on-top-of-the-world noise pop comic song à la Flight of the Conchords. It captures the story’s juxtaposition of wretched and witty, leaving plenty of room for existential rumination.

Wolf Alice, “Lisbon”

Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides centers on the Lisbon family and their five teenage daughters, each of whom meets a disturbing fate by the novel’s end. It’s a joyless and challenging read with underage sex and suicide, unreliably narrated by local neighborhood boys. The story is easier to experience through Wolf Alice’s “Lisbon” from their debut album My Love Is Cool. The menacing dream-pop track funnels the Lisbon girls’ trauma into a single-string guitar riff paired with Ellie Roswell’s airy, almost indistinct vocal murmurs. Gloom gives way to an almost euphoric synth-slathered outro, as though the storyteller or her subjects are submitting to the darkness and extracting comfort from its insulation.

The Velvet Underground, “Venus in Furs”

The Velvet Underground’s most notable literary reference is surely its name, lifted from the title of a book about New York’s sexual subcultures. Similarly, “Venus in Furs,” the darkest skirmish on the 1967 masterpiece The Velvet Underground & Nico, is named for Venus im Pelz. Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s 1870 book about masochism—a term coined from the Austrian writer’s surname—tells a story within a story. The unnamed narrator reads a book in which a man named Severin becomes so obsessed with a woman, Wanda, that he begs to be made her slave. The atypical arrangement goes awry when Wanda falls for another man and desires her own domination. Droning Ostrich-tuned guitars and John Cale’s screeching violin mirrors the peculiarity of this fable, while Reed’s lyrics hit all the required sadomasochistic beats—“Shiny boots of leather,” “taste the whip,” and “Severin, down on your bended knee.”

Patti Smith, “Banga”

Patti Smith’s “Banga” is her tribute to loyalty, patience, and unification—attributes aptly embodied by man’s best friend. In this case it’s Banga, Judaea governor Pontius Pilate’s dog from Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. Banga was loyal to his owner for 2,000 years, and his sole source of joy. “And the paw is pressed against the nerve of the sky / You can leave him behind, but he won’t leave you,” Smith drawls. Heavily censored by the Soviet government upon publication, the supernatural novel follows the Devil’s visit to the non-religious Union, exploring good versus evil through a plethora of absurdist characters—including Satan, a cat, a hitman, and a vampire. With the Johnny Depp on guitar and drums, the song is Patti Smith’s trademark propulsive art rock, the lyrics a hollering speak-sing, a handful of primitive chords vacillating in accompaniment.

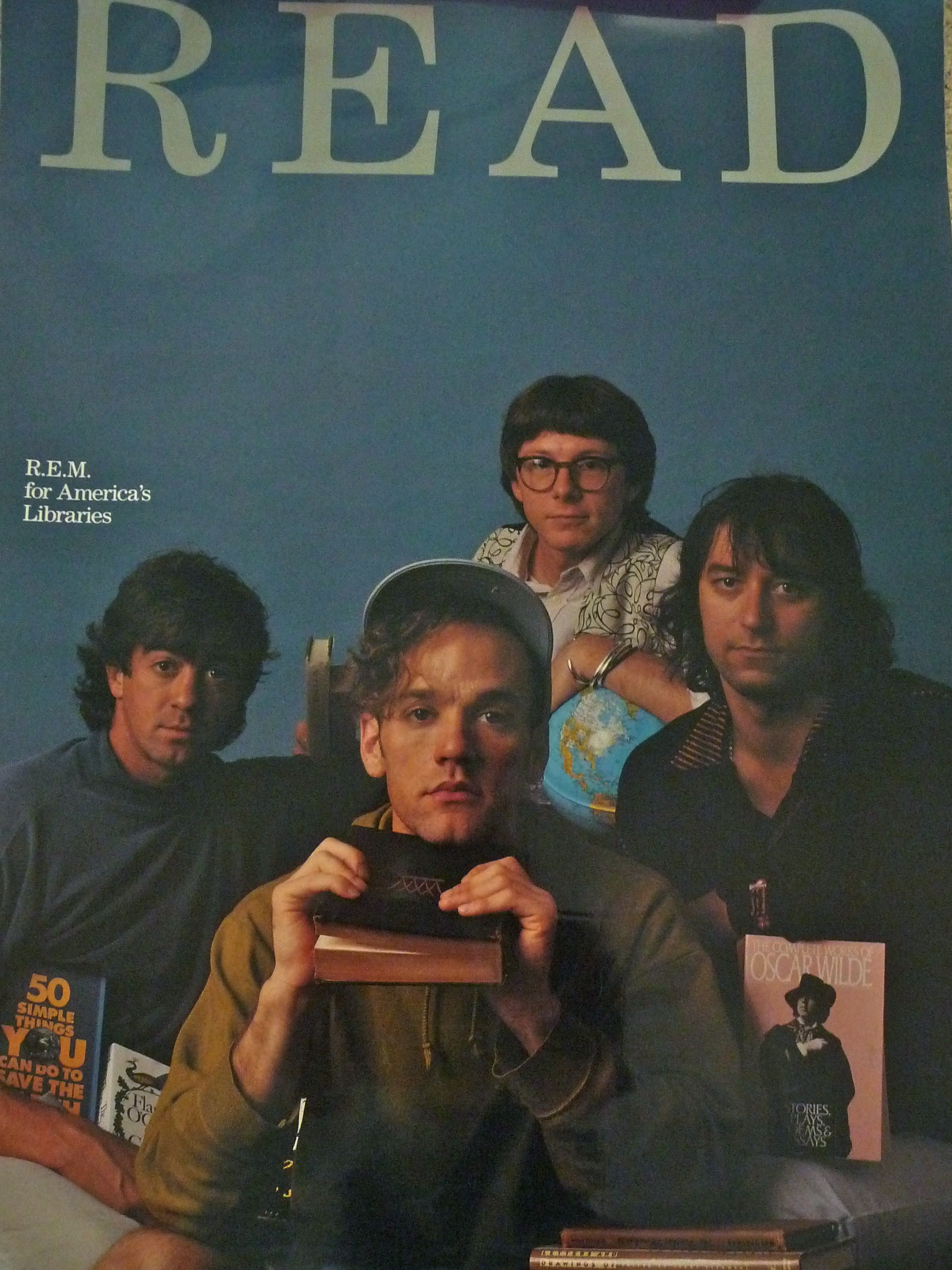

R.E.M., “Disturbance at Heron House”

“Disturbance at Heron House”—and R.E.M.’s politically charged fourth LP Document—was a way for Michael Stipe and company to vent their discontent at the Reagan administration, which was deep into its second term of trickle-down conservatism and victimization of minority groups by the song’s release in 1987. Taking George Orwell’s Animal Farm as a blueprint, the band devised their own zoological allegory for a failed revolution. “When feeding time has come and gone / They’ll lose the heart and head for home,” Stipe sings in his mumbly baritone over Peter Buck’s jangling Rickenbacker and a slowed motorik drum beat. The titular Heron House derives from the word Herrenhaus, meaning a house of lords or mansion. And since its release, the song has flitted in and out of the band’s live setlists depending on who’s currently in office, serving as a disenfranchised boomer’s subtler alternative to “American Idiot.”

Green Day, “Who Wrote Holden Caulfield?”

Green Day and The Catcher in the Rye both left subversive, humble beginnings for mainstream acclaim, but while Billie Joe Armstrong embraced the limelight, J.D. Salinger absconded to rural New Hampshire to live the remainder of his life as a recluse, his final work publishing in 1965. The Oakland trio’s slacker punk paean “Who Wrote Holden Caulfield?” sees the 19-year-old Armstrong paying homage to Holden shortly before he was cemented as a similarly influential voice of the MTV generation. Catcher was the novel that was in Mark David Chapman’s pocket when he murdered John Lennon and was, for a time, simultaneously the most censored and most widely taught literature in America’s public schools. Like Green Day’s early music, the book serves as a pocket journal for directionless youth, striking a power chord with iconoclasts and suburban burnouts years later.

Eddie From Ohio, “Sahara”

Whether Christopher McCandless is an enlightened luminary or an irresponsible zealot, there’s no question that his story is influential. At 24 years old, after graduating from university and donating his life savings to Oxfam, “Alexander Supertramp” headed for Alaska’s Stampede Trail, accompanied by only nine pounds of rice, a rifle, a camera, and a few precious paperbacks. He starved to death 113 days later. After tracing the abstemious vagabond’s steps for the 1993 article “Death of an Innocent,” Jon Krakauer expanded the story for his book Into the Wild. Virginian folk quartet Eddie From Ohio meditates on McCandless’ incredible journey on “Sahara,” whose coalition of enchanting acoustic guitars captures the same glacial poignancy as Krakauer’s text. The arrangement glistens like the Teklanika River reflecting the summer sun, while dual vocalists Julie Murphy Wells and Robbie Schaefer coo their ode: “Guided by Tolstoy and the moon / Into the Yukon he would go / In search of a higher truth.”

Jimmy Eat World, “Goodbye Sky Harbor”

Before Jimmy Eat World became emo godfathers and daytime radio mainstays, they flirted with an experimental streak. Closing their 1999 masterstroke Clarity is “Goodbye Sky Harbor,” three minutes of charging rock that gives way to a 13-minute instrumental coda—fizzing organs, wordless vocal loops, and layers of glistening guitars. It’s within these first three minutes that Jim Adkins shares lines from John Irving’s A Prayer for Owen Meany. The 1989 novel, which culminates at Arizona’s Sky Harbor airport, centers on two friends coming of age in a small New Hampshire town: John Wheelwright (the narrator) and Owen Meany. Owen is the smallest kid in school, has a shrill voice—all his dialogue is in capital letters—and believes it’s his mission to satisfy the will of God. With themes of fate and spirituality, the backdrop of the Vietnam War, and a foul baseball that kills John’s mother, it’s a moving and hilarious read elevated by Jimmy Eat World’s kraut-pop-punk soundtrack.

Belle and Sebastian, “I Fought in a War”

Fold Your Hands Child, You Walk Like a Peasant is a curiously specific album title, as though lifted from literature rather than, in actuality, bathroom stall graffiti. “The more obscure and would-be literate, the better,” Stuart Murdoch says in the sleeve notes for the record. Belle and Sebastian’s character-driven songs unravel like novellas, and one in particular, “I Fought in a War,” is inspired by J.D. Salinger’s semi-autobiographical wartime short, “For Esmé—with Love and Squalor” (the subtitle of which also leant itself to the debut album from indie rockers We Are Scientists). The story focuses on a conversation between an American soldier stationed in Britain just prior to the D-Day landings and a young choir girl named Esmé, who impresses the soldier with her maturity and promises she will write to him. The song’s narrator, like Salinger’s protagonist, is waiting for a letter to arrive, kept company by soldierly brass and plaintive guitar arpeggios.

Laura Marling, “The End of the Affair”

On the surface, Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair is about adultery—an affair and its impact on three interwoven lives. But the bigger significance is having to mourn a lost love in private because of its prohibition. This is the part that resonated with Laura Marling, the British indie-folk artist who explores the concept on her song of the same name. What ends Greene’s affair—well, his novelistic counterpart Maurice Bendrix’s—is a stray WW2 bomb that strikes his apartment. His lover vows to God that if Bendrix survives the blast, then she will never see him again. “But now we must make good on words to God / And sit with a weary breath,” Marling lilts over sparsely thumbed chord inversions. At the end of her poignant break-up monologue, she re-packages the final lines of the novel, a laconic yet merciful termination: “I love you, goodbye / Now let me live / My life.”