This cover story appears in FLOOD 13: The Tenth Anniversary Issue. You can purchase this special 252-page print edition featuring Gorillaz, Magdalena Bay, Mac DeMarco, Lord Huron, Bootsy Collins, Wolf Alice, and much more here or at Barnes and Noble stores across the US.

“I don’t think we thought much further than that first picture and first demo,” says Damon Albarn, speaking from Devon, where he’s been rehearsing for a four-night run at London’s Copper Box Arena to celebrate the 25th anniversary of what was once assumed to be the Blur frontman’s side-project: cartoon art-pop/hip-hop collective Gorillaz. “I just thought, ‘Hey, I really like this guy. He’s really clever. I would really like to spend some more time with his mind.’ And maybe he thought the same of me.”

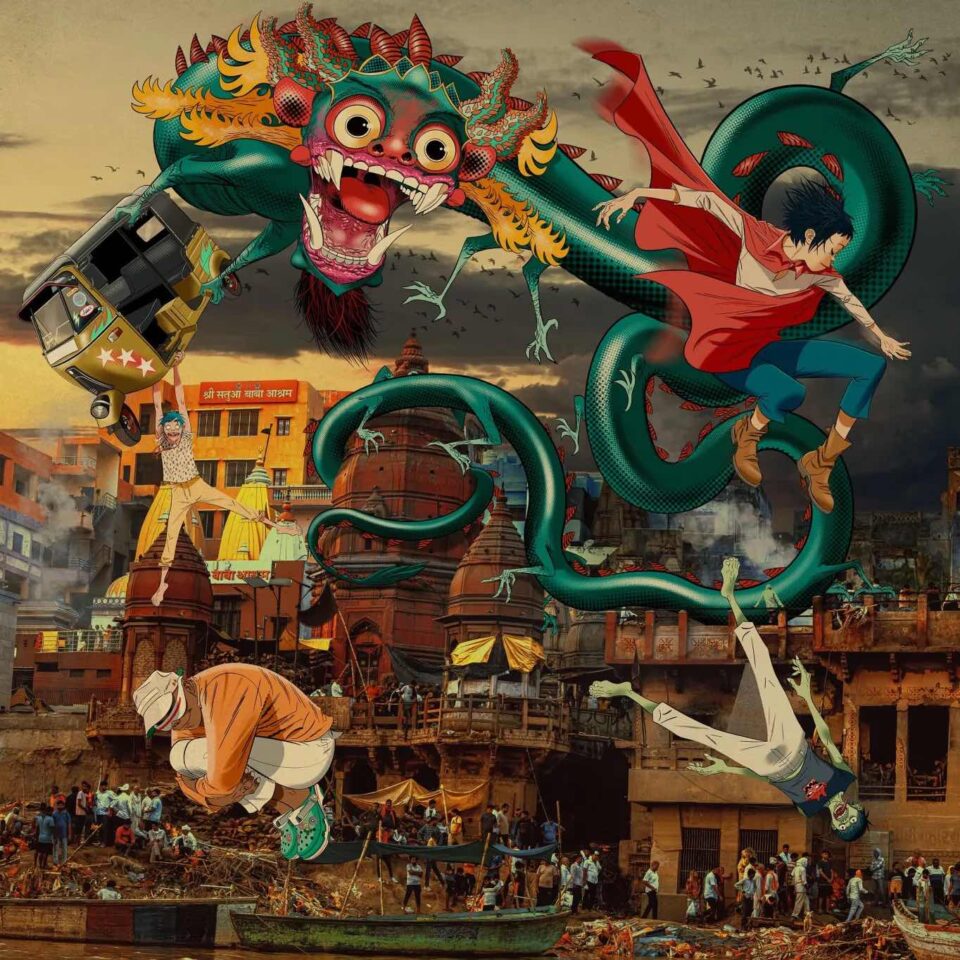

The guy Albarn is referring to is his onetime Notting Hill flatmate, Tank Girl comic artist, and Gorillaz co-creator Jamie Hewlett, who he says is “as close to a brother as I have.” While Albarn and Hewlett have, over the course of eight albums, invited a dizzyingly impressive array of flesh-and-blood musical icons into their virtual world (Bad Bunny, Beck, Peter Hook, Elton John, Grace Jones, Stevie Nicks, Robert Smith, Tame Impala, and St. Vincent, to name but a few), it’s their real-life bond that’s truly at the beating heart of Gorillaz. And that’s perhaps more true than ever as they prepare to release Gorillaz’s full-circle ninth album, The Mountain, which Albarn describes as a “double-headed beast of grief and wonderment” inspired by a spiritual trip he took with Hewlett. “It feels like we’ve kind of got our mojo back a bit,” Albarn says fondly. “It’s been the easiest, I think, that it has been for a very long time. And that’s partly because we went on some pretty involved, pretty heavy adventures in India.”

But before we take that journey to The Mountain and Varanasi, we must take a journey to the west—back to West London circa 1998, where Albarn and Hewlett came up with the Gorillaz concept while watching MTV in their shared Westbourne Grove bachelor pad. “It was that time when that Blur-versus-Oasis thing was getting very stale, and everything was becoming the same. The idea was to create something that we felt would be an antidote for what was happening in the scene,” Hewlett recalls. “There were a lot of manufactured bands, and they were all manufactured very poorly. We just thought, ‘If you’re going to manufacture something, why not do it properly?’”

At the time, Albarn was NME’s posterboy of Britpop (“Which apparently is back!” he smirks), and he was eager to adopt an entirely new persona. “It just felt like the most exciting thing that you could possibly do was to sort of disappear and start again,” he muses. “The thing I look forward to most is seeing if I can do something that completely redefines who I am. Not all of my reinventions have been as successful as I would’ve liked them to be, maybe. But it is something I enjoy—not being able to entirely rest on your previous success.”

“There were a lot of manufactured bands, and they were all manufactured very poorly. We just thought, ‘If you’re going to manufacture something, why not do it properly?’” — Jamie Hewlett

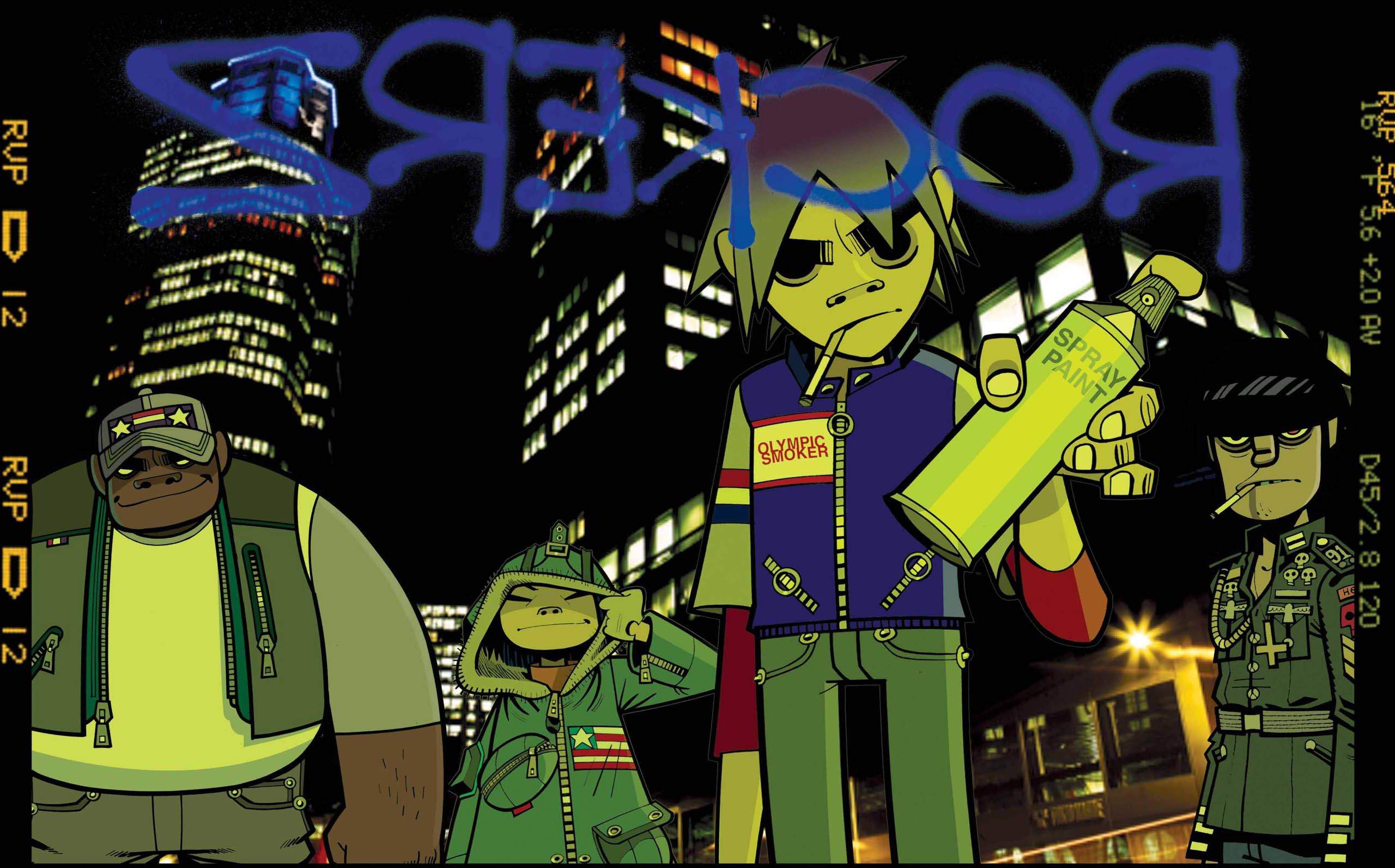

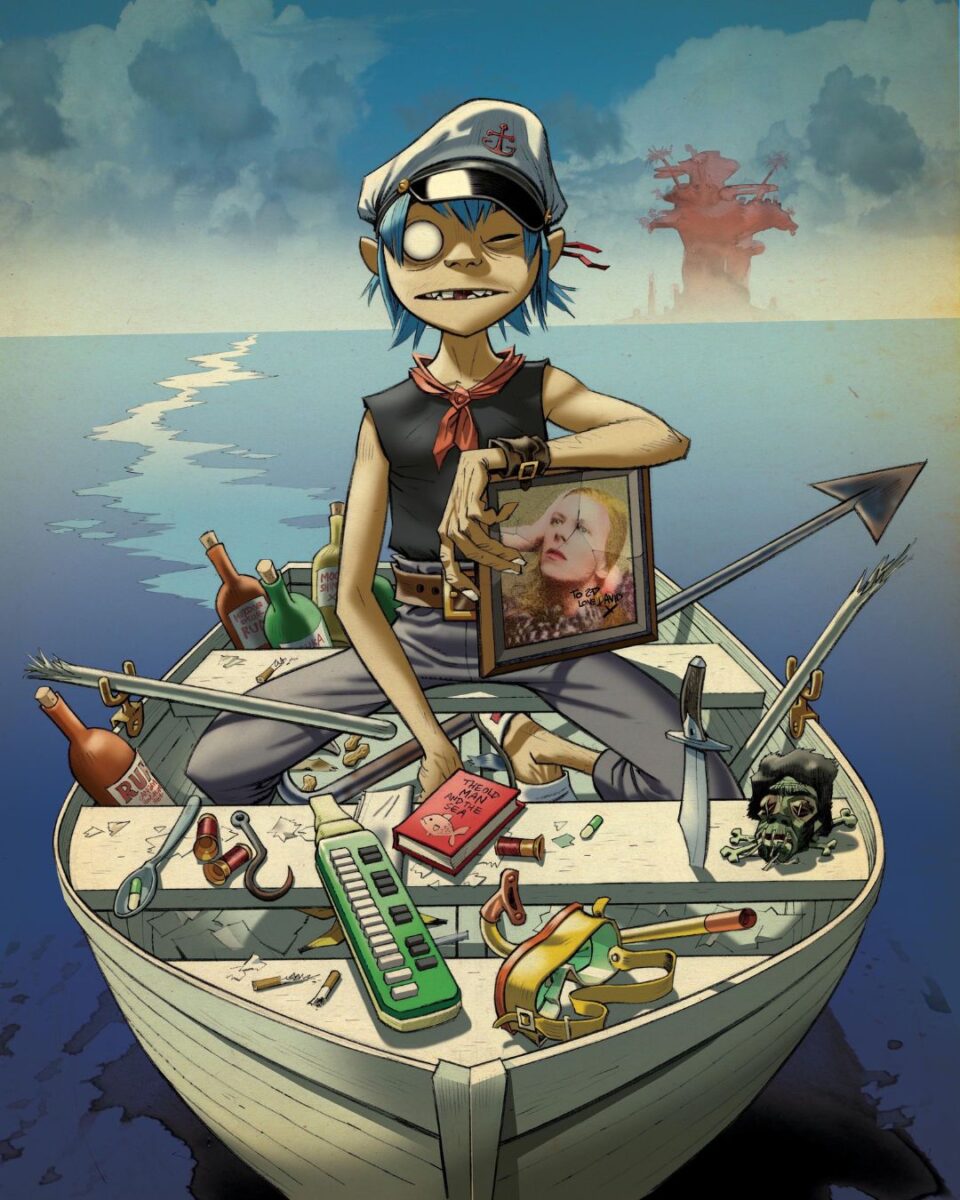

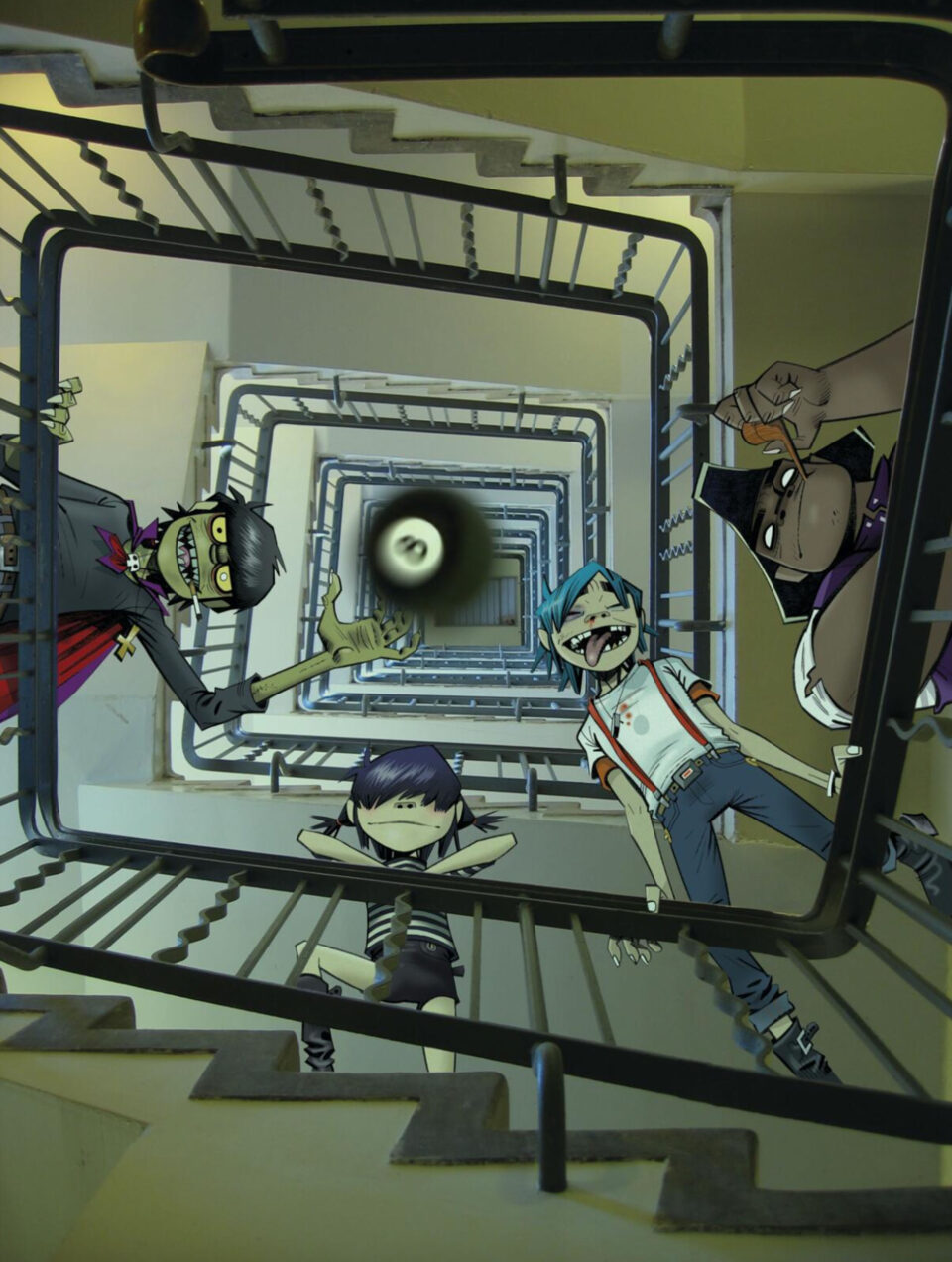

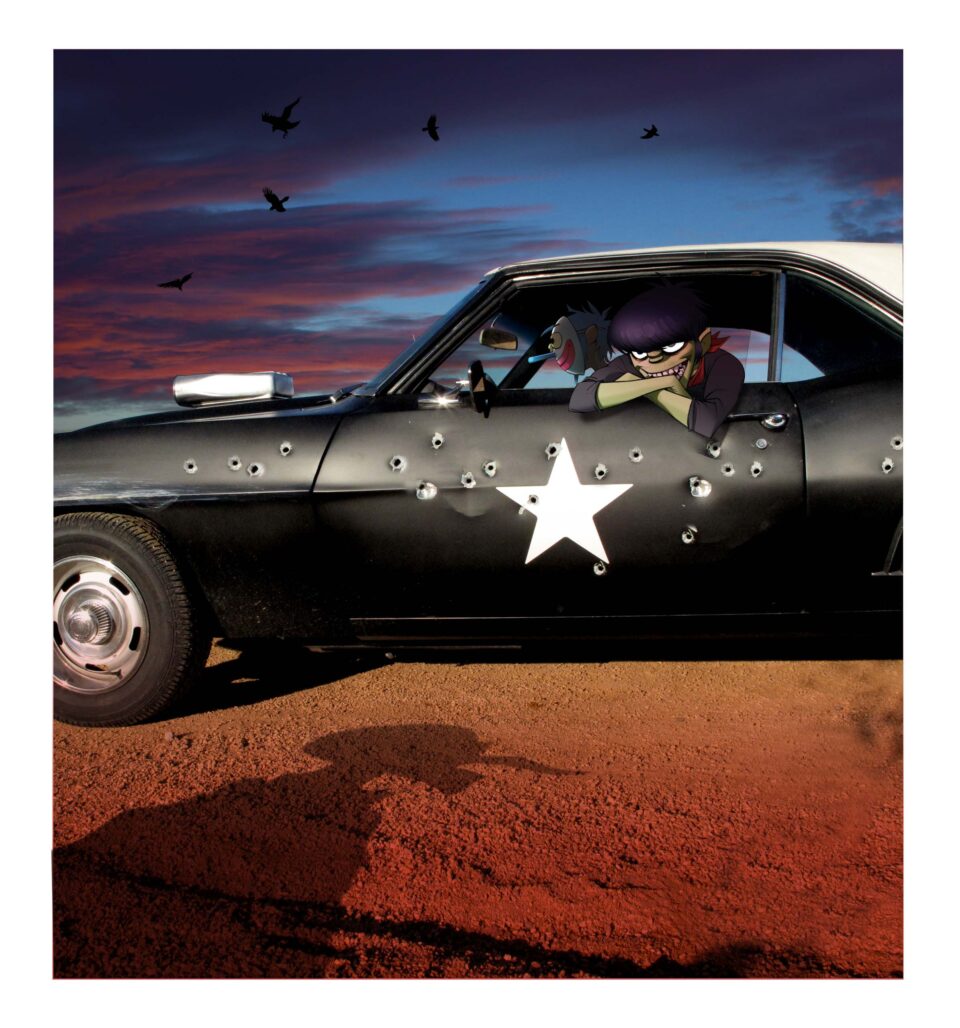

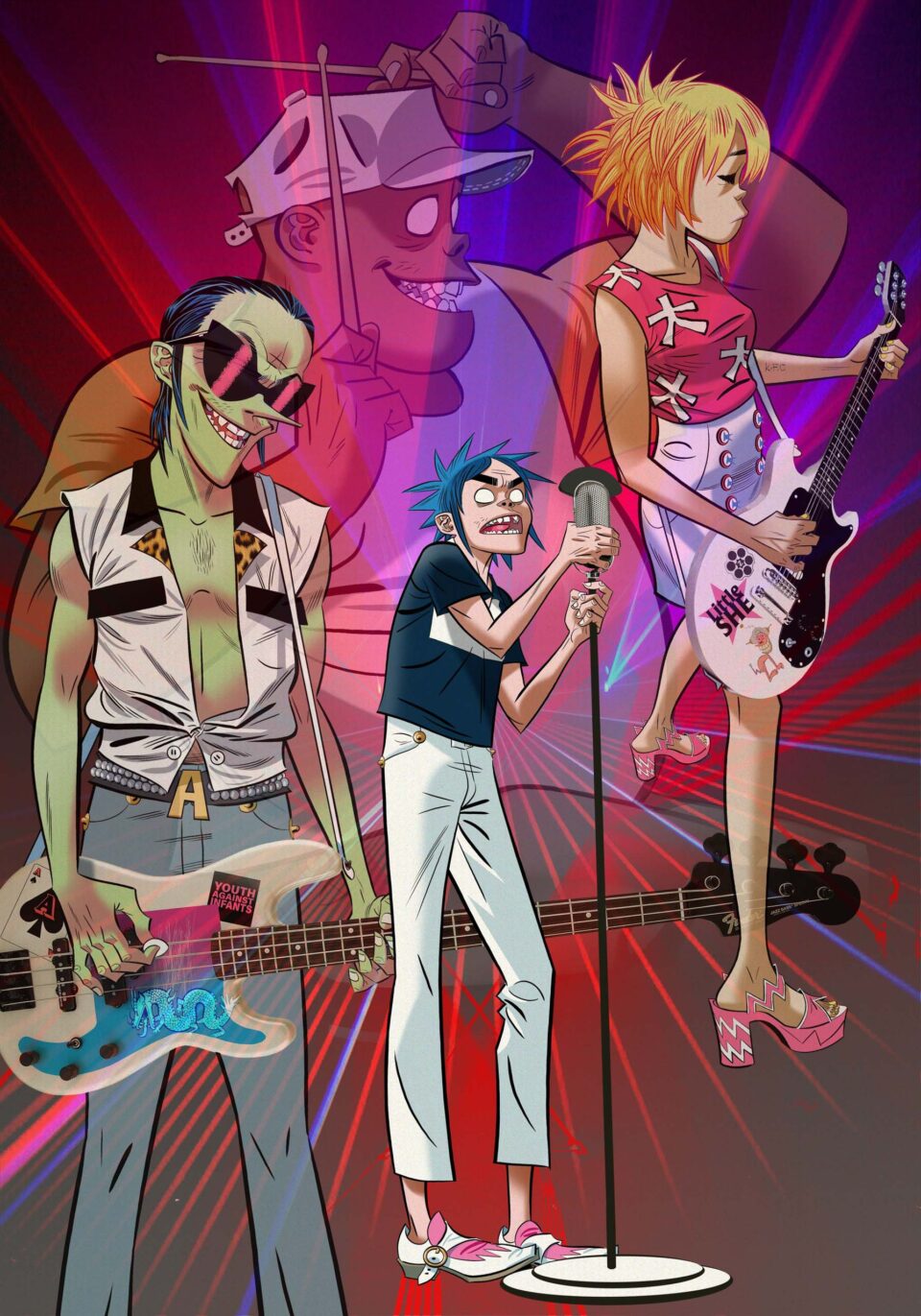

The next day, Albarn went to work in his studio on Gorillaz’s first song, a bonkers punk-reggae party jam called “Ghost Train,” while Hewlett began rough sketches of Gorillaz’s four members: speed-freak bandleader and bassist Murdoc Niccals, vacant-eyed frontman 2D, gangster drummer Russel Hobbs, and Japanese child guitarist Noodle. Hewlett says he pulled from Hayao Miyazaki’s early animated film Castle in the Sky, The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine, Sex Pistols’ Great Rock ’n’ Roll Swindle, the sci-fi classic Fantastic Planet, Looney Tunes, and even the Jackson 5’s kiddie cartoon series, as well as from Cartoon Network’s ’90s heyday and shows like Powerpuff Girls, Dexter’s Laboratory, Ren & Stimpy, and Futurama.

The concepts came quickly, except when it came to the plucky young Noodle. “There were a few different female characters when trying to design the lineup, which is mentioned in the exhibition in London,” says Hewlett, referring to Gorillaz’s career-spanning House of Kong retrospective that ran at Copper Box this past August and September. “I couldn’t get the female member of the band quite right.” While Murdoc was modeled after Keith Richards in his junkie-chic prime, Russel was an homage to old-school American rappers like Ice Cube, and 2D was obviously a two-dimensional representation of Parklife-era Albarn himself, Noodle became a nod to AC/DC’s Angus Young. “I remember seeing Angus onstage and thinking, ‘That’s so cool! He’s wearing his school uniform and he’s got long hair and he’s just playing this guitar! Wow!’ Something about that really blew my mind, and that was sort of in the back of my mind for having Noodle as a kid with a guitar.”

Equipped with “five drawings and one demo,” the flatmates then pitched Gorillaz to Parlophone Managing Director Tony Wadsworth, who, as Hewlett recalls, “instantly understood and said, ‘Yeah, we’ll do it!’” Looking back, Gorillaz had genius timing, as it was perfectly in tune with Y2K—a youthquaking, fantastic-plastic age of novelty, optimism, and futurism, as promised by the title of their 2000 single “Tomorrow Comes Today.” But in the beginning, they had few industry supporters besides Wadsworth. “Nobody was buying into the idea of an animated band,” recalls Hewlett. “I think they just felt that was for children. Coming off the back of the ’90s, where it was all rock ’n’ roll and lad culture and football culture, it really didn’t fit. But for me, animation had always been something that I considered for adults, as well.”

“It’s not just a gimmicky cartoon. They’re as real as any other band,” Albarn told Yahoo in 2001. “In a way, it’s more honest, because celebrities and pop stars have to lie all the time about their private lives.”

Albarn and Hewlett had in fact even created an entire elaborate backstory about the personal lives of Murdoc, 2D, Russel, and Noodle. This involved, among other comic-book plot twists, Murdoc meeting 2D after he crashed his car into a London organ shop and sent 2D into a coma, then being court-ordered to become the brain-damaged 2D’s caretaker and bandmate; Murdoc and 2D meeting Russel while burglarizing Russel’s Soho record store; Noodle answering their “guitarist wanted” advert by FedExing herself to her audition; and Russel undergoing an Exorcist-style demonic possession that left him with the ability to contact the dead (more on that later). Albarn and Hewlett then, according to Gorillaz lore, met the rag-tag gang in Leicester Square and became their spokesmen and managers, or “human representatives.”

Albarn and Hewlett actually never intended to do promotion for Gorillaz as themselves, but only i-D magazine was willing to go along with the gag, putting the characters on the cover and giving them an eight-page editorial. After Gorillaz broke through with “Clint Eastwood,” their dubby, The-Specials-go-Spaghetti-Western single assisted by Del the Funky Homosapien, the media’s demand for them surged. (Incidentally, that song went to #57 in America, and Gorillaz’s self-titled album peaked at #14 on the Billboard 200—both higher than any US ranking Blur ever achieved.) But, as Hewlett recalls, “Everyone just wanted to talk to the ‘real’ guys. We paraded it around to various magazines to try and get them to interview the characters and play the game, but nobody really wanted to do that.”

“That was still when we were very much crusaders of anonymity,” Albarn adds. “Really the only one from that era who’s managed to do it at all successfully is our friend, Banksy. We weren’t able to keep hold of the narrative of it just being a band and us being anonymous. We failed miserably at that.”

“We weren’t able to keep hold of the narrative of it just being a band and us being anonymous. We failed miserably at that.” — Damon Albarn

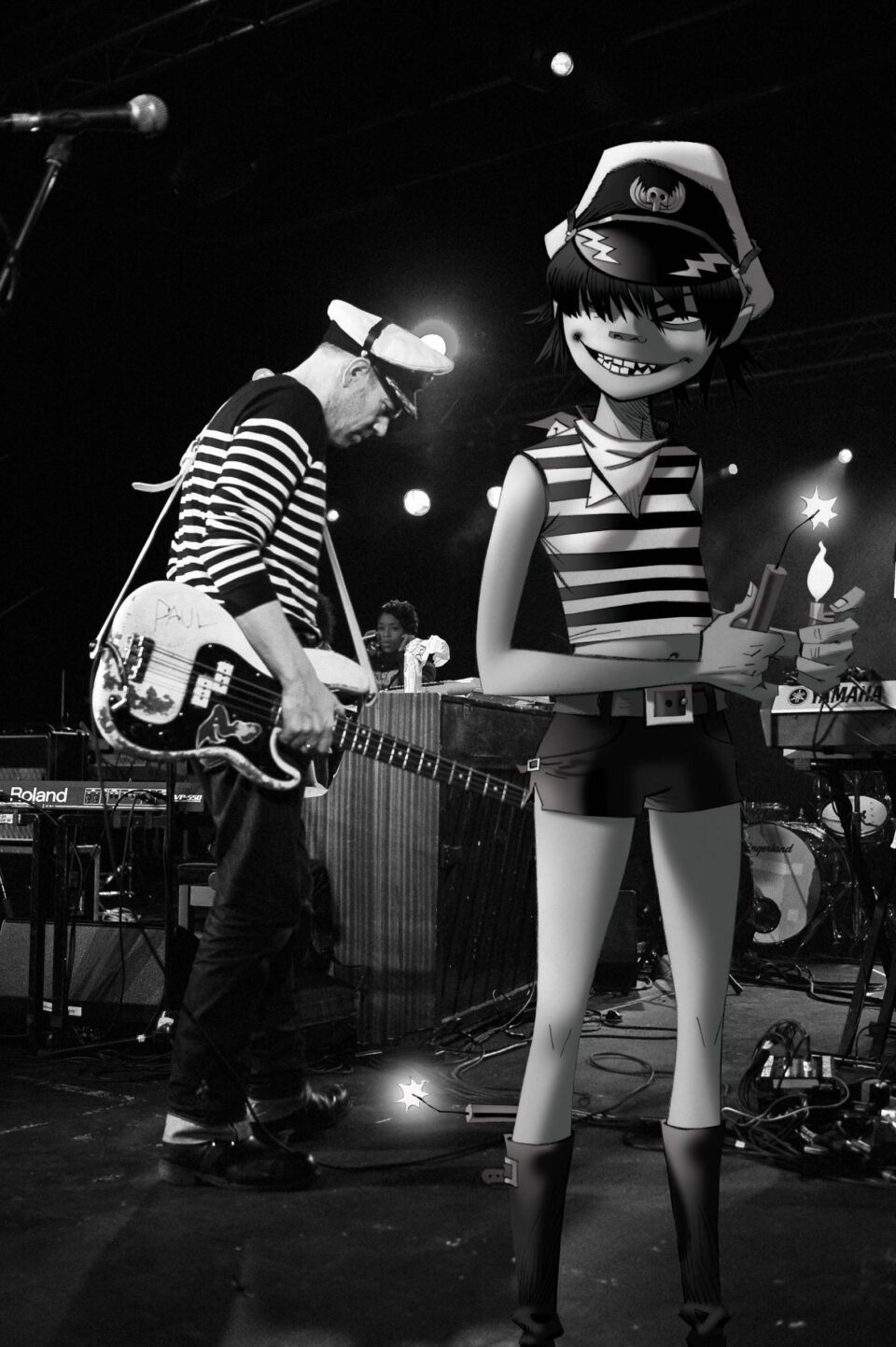

Gorillaz’s buzz eventually led to them actually taking the live stage, albeit with Albarn and other mystery musicians shrouded in shadow behind a video screen, while Murdoc and company’s Technicolor images entertained the confounded crowd on a 50-foot monitor. It all started with a historic (if, in retrospect, amusingly lo-fi) March 2001 gig at London’s Scala, which was recently recreated on night one of Gorillaz’s album-by-album Copper Box residency. By the time Gorillaz really exploded four years later with their sophomore album Demon Days’ smash single “Feel Good Inc.,” technology had started to catch up with their ambitions when it came to concert performances. They even got to open the 2006 GRAMMY Awards—with Madonna—as holograms.

But not everything went off without a hitch that night, and what transpired was as amusing and over-the-top as anything in rabblerouser Murdoc’s fictional biography. “Jamie and I arrive in Los Angeles, and we get a phone call from Dennis Hopper,” Albarn begins. The rebellious New Hollywood actor had appeared on the Demon Days track “Fire Coming Out of the Monkey’s Head,” and he wanted to give his new pals a warm GRAMMY eve welcome, because “Feel Good Inc.” had received an unexpected nomination for Record of the Year. “So, we go to his mansion, a very interesting place—huge, with the most ridiculous art on the walls. It was a party like we’d never been to before, and it was held in our honor, and it felt like a really big deal. And we got way, way too overexcited that night, and we were still kind of going [the next day]. So we arrived somewhat worse for wear in the heat on the red carpet. And as we were walking down there, Jamie got a phone call from one of our friends, saying, ‘I’m watching this dodgy cable fashion show, which is coming live from the GRAMMYs’ red carpet, and you’re the center of conversation for how bad you both look!’”

“Nobody was buying into the idea of an animated band. I think they just felt that was for children. Coming off the back of the ’90s, where it was all rock ’n’ roll and lad culture and football culture, it really didn’t fit.” — Jamie Hewlett

During the iconic Gorillaz/Madonna opening performance that evening, the rumpled Albarn and Hewlett weren’t actually onstage, but in the Staples Center audience with everyone else. “I remember we were sitting behind U2, and Bono was wearing a particularly tall hat, which immediately obscured my view,” Albarn recalls. “And then it started, and you couldn’t hear anything—because to create that hologram, it was a piece of basically cling-film pulled over half of the stage, and then smoke or some kind of ionizing gas was pumped behind it. The caveat was that you couldn’t have any volume, because it vibrates the film. So everyone around us was not aware that it was even happening. It was supposed to be our big moment, and I was trying to look over Bono’s hat to see it, and I couldn’t hear it, and no one seemed to know what was going on. And then [Gorillaz] finished, and Madonna walked over to the other side and the speakers switched on, and everyone went, ‘Ahhh!’ I know on television it looked incredible, but at that moment in time, we felt terribly deflated and hungover. And I was somewhat indignant when I went to see Madonna in her dressing room afterward and I got pushed out of the way in the corridor by her bouncers—literally pinned to the wall as she’s walking through. So, yeah, that was my experience at the GRAMMYs.”

“Feel Good Inc.” didn’t win Record of the Year that night, and while Gorillaz’s performance was no doubt groundbreaking, predating Coachella’s Tupac hologram and other similar extravaganzas by many years, Albarn’s dreams of an all-hologram Gorillaz tour never materialized. “I’m still moaning about that. I’d just imagined it wouldn’t be long before I could be sitting at the piano and whoever I wanted—whoever the band had worked with—would just turn up as a hologram,” he says. (Spoiler alert: That sort of happens, sonically, on The Mountain.) “I was actually a bit upset about ABBA Voyage [the Swedish pop group’s virtual avatar concert experience in London]. I can’t bring myself to go, when that was our idea!”

“The cartoon thing is really what sold it to us. It honestly felt like something we would’ve done at some point.” — De La Soul’s Kelvin “Posdnous” Mercer

However, with “Feel Good Inc.,” Gorillaz had arrived in a major way. The song, featuring New York boom-bap pioneers De La Soul, did win the 2006 GRAMMY award for Best Pop Collaboration (beating out Recording Academy darlings like Foo Fighters & Norah Jones and Stevie Wonder & India.Arie), and it was an international sensation, cracking the top 10 in 16 countries. It also kicked off a beautiful friendship between Albarn and one of Gorillaz’s most frequent and long-running collaborators. “De La Soul was so important to me growing up, even though they’re the same age as me. They were an influence on me because they started so young,” says Albarn. “I really feel like Gorillaz is in part them. I feel like they embody it so much, the aesthetic and the spirit of it.”

“The cartoon thing is really what sold it to us,” says De La Soul’s Kelvin “Posdnuos” Mercer, recalling the trio’s fateful first meeting with Albarn. “It honestly felt like something we would’ve done at some point, like, ‘Yo, let’s just do a cartoon and make a whole album around it!’ That’s just us. We went to London, and Damon pulled up to the studio on his bike, and he had a Mickey Mouse shirt on. From there, we became kindred souls. And it’s a family thing at this point. We’ve been family for a long time. It’s beyond music. It really is. We love that man. That’s our brother.”

When Albarn first played beats for De La Soul, the track that initially caught their attention was the moody and shouty (and definitely less feel-good) “Kids with Guns,” which was eventually recorded for Demon Days with Neneh Cherry. “We started working on ‘Kids with Guns’ for two days. We put rhymes to it and everything,” Mercer says, revealing that they’d even recorded a version of the single that was never released. It was on the second day that Albarn played some other rough music for De La’s Dave “Trugoy the Dove” Jolicoeur. “Dave was with Damon in this little control room, and he runs out to me, like, ‘Yo, you gotta hear this!’ And we come in, and it’s ‘Feel Good Inc.’ He was like, ‘This is the song. We gotta get on this!’” Mercer recalls. “And the rest, as they say, is history.”

Despite Jolicoeur’s conviction and the bass-heavy tune’s undeniable funky-freshness, “Feel Good Inc.” was still a surprise success to most. “We thought the song was really, really great, but we had no idea that record was going to do what it did. None,” admits Mercer. And nothing illustrates that point more than the fact that Mercer actually opted not to appear on “Feel Good Inc.”—leaving De La Soul’s DJ, Vincent “Maseo” Mason, to contribute that iconic cackle (“That’s how he literally laughs,” says Mercer) and Jolicoeur to write the raps. Mercer and Albarn have different recollections regarding why this happened—Mercer claims he was busy finishing up De La’s album The Grind Date, while Albarn says he “decided to have a haircut instead… which obviously to this day he regrets, because he doesn’t get that royalty statement every quarter!”

Both Albarn and Mercer agree that the track turned out perfectly, however. “Damon had the space open, and Dave stepped to the plate and filled the space immediately. He got it done that night,” says Mercer of his bandmate, who passed away in 2023. “That’s how creative Dave was—I think being creative and a little high at the same time. He was always like that. He could see colors and whatever, and when he’s inspired by a record, he just knocks it out. I think he did it within twenty-something minutes.” Mercer says he was offered an opportunity to come up with his own “Feel Good Inc.” rhyme once he was back in New York, “but I was just so wrapped up in finishing The Grind Date that they was like, ‘You know what? This is just the way it’s going to be.’ And I was like, ‘Nah, that’s cool.’ I understand when lightning strikes. To try to force something afterwards, it just wasn’t meant to be.”

Mercer, of course, would have many other opportunities to feature on Gorillaz songs, starting with the power-pop romp “Superfast Jellyfish,” a delightfully quirky duet with Super Furry Animals’ Gruff Rhys, on Gorillaz’s next album, 2010’s Plastic Beach. “When that beat dropped in… that Saturday morning cartoon vibe? And talking about cereal? We immediately caught that,” smiles Mercer. “The rhyme was free-forming. The ad-libs were funny. It felt, quite honestly, like, ‘Wow, this is like 3 Feet High.’”

“I think the beauty of Gorillaz is, when you strip it all down to being creative, everyone is on the same level and equally vulnerable in the creative process.” — Little Dragon’s Yukimi Nagano

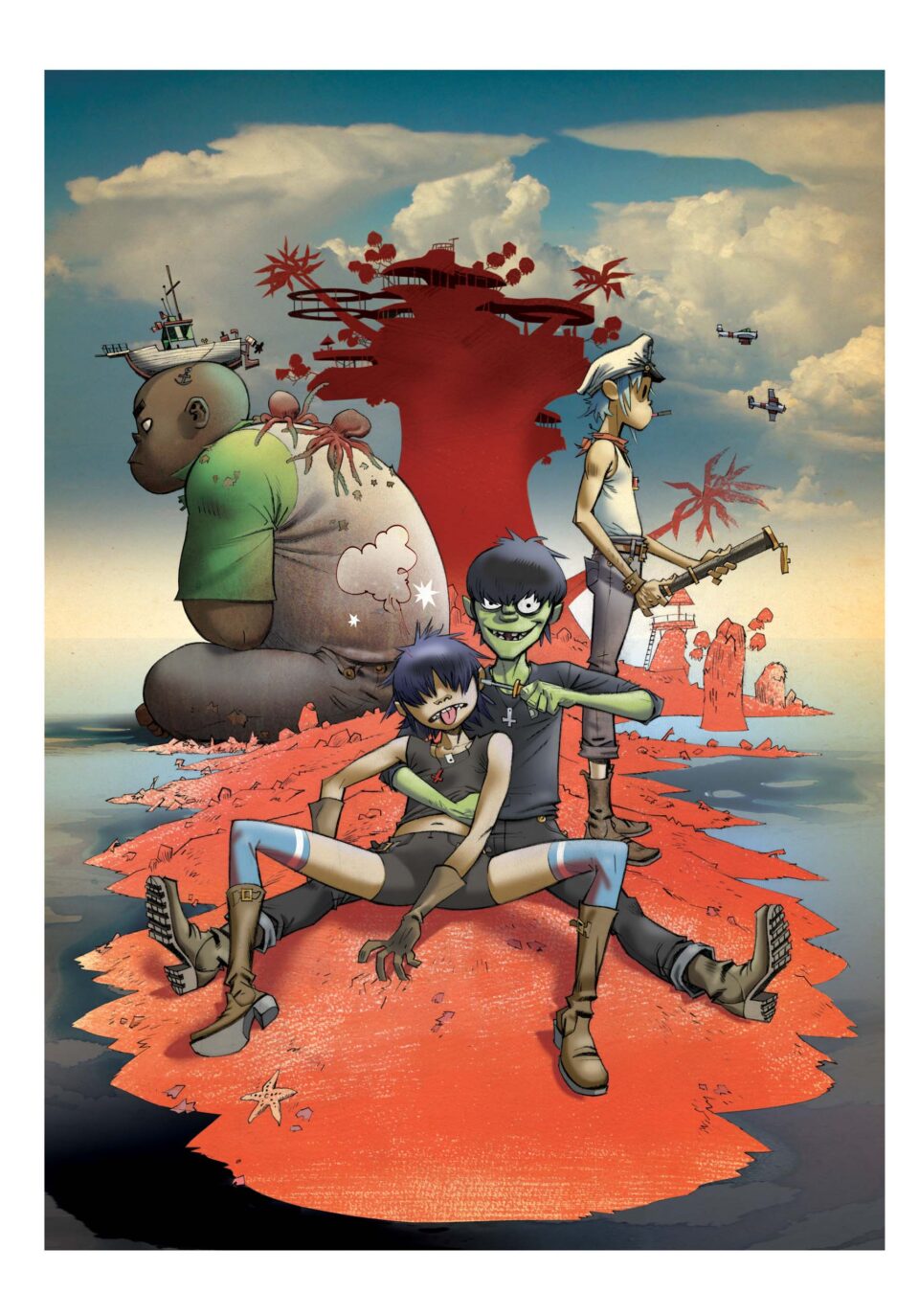

If Gorillaz had put Albarn and his cartoon sidekicks on the musical map, and Demon Days had made them GRAMMY-winning pop sensations, it was the ambitious Plastic Beach that made them arena superstars. Gorillaz’s first two LPs were obviously guest-heavy, but Plastic Beach boasted an A-list track listing that read like a wildly diverse, impeccably curated festival lineup: The Clash’s Mick Jones and Paul Simonon, Swedish indie-pop band Little Dragon, Mos Def, Snoop Dogg, Lou Reed, The Fall’s Mark E. Smith, and the collaborator that Albarn is still the most proud of securing, the late soul superstar Bobby Womack.

Little Dragon’s Yukimi Nagano, who co-wrote and sang on two Plastic Beach tracks, knew little about Gorillaz when she signed on, and she was not at all prepared to be part of such a phenomenon when, just one month after the record’s release, she joined Gorillaz as they headlined Coachella and embarked on a world tour. “It was such a profound experience,” she says, “and such a big, inspiring chapter in our whole careers. Coachella was a turning point. It was just such a big stage, and we were closing that stage. It felt like a dream. I remember getting offstage and being tapped on the shoulder by Beyoncé saying, ‘Good job!’ And I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is just too much for me!’ And that tour was such a crazy, huge production, with so many artists from different genres, different ages, different worlds, all on the same stage together. There were six tour buses and eight trucks or something, and for us just being an indie band used to playing in little clubs, it was the first time that we had a chance to play such huge stages.”

Nagano and Mercer have plenty of anecdotes about their large-scale shows with Gorillaz—which featured no holograms, but plenty of all-stars—with Nagano recalling a “big fight breaking out backstage in Paris between the Hypnotic Brass Ensemble and some UK rappers; I think it was Kano and Bashy,” and Mercer recalling a literally crappy gig in Syria when everyone in the crew but Albarn came down with diarrhea. “But we had to perform! There was this beautiful restaurant across the street, and they’d paid the restaurant to have only Gorillaz people use the bathroom, so we could be running back and forth using the bathroom during our show. We felt so bad for the string players, because they were a very intricate part of the show, so they just had to sit there and try to hold it.”

But mostly, they fondly reflect on the bonds they forged during that time. “You all become friends and it becomes one big family,” says Nagano. “There’s gossip and there’s a bunch of drama as days become weeks, and then finally you’re really close. One of the big things for me was we shared the bus with Bobby Womack, and [he] had so many stories. He could just throw names out, like, ‘Oh, Marvin Gaye, we used to play football together,’ or ‘I called Aretha Franklin yesterday.’ He knew everybody, and had stories about everybody, and was such a sweet, humble guy, as well. I remember playing him demos of Little Dragon’s upcoming album, Ritual Union, and him being very encouraging. Of course, there are a bit of nerves when you go into a situation like that, but I think the beauty of Gorillaz is, when you strip it all down to being creative, everyone is on the same level and equally vulnerable in the creative process.”

Albarn, who Nagano describes as “a very spontaneous, creatively explosive person,” wrote and recorded 2010’s song-sketchy The Fall, the first major album release to ever be recorded entirely on an iPad, during the North American leg of the “Escape to Plastic Beach” tour. There wouldn’t be another full Gorillaz album until Humanz came out seven long years later. “After that Plastic Beach album cycle, Damon had said, ‘OK, so this is going to be the last Gorillaz album,’” Mercer recalls. “And I had young kids in my neighborhood coming to my house, crying: ‘Mr. Mercer, we heard that this is the last Gorillaz album! Is that true?’ And I was like, ‘Oh my God, I got kids crying at my door!’”

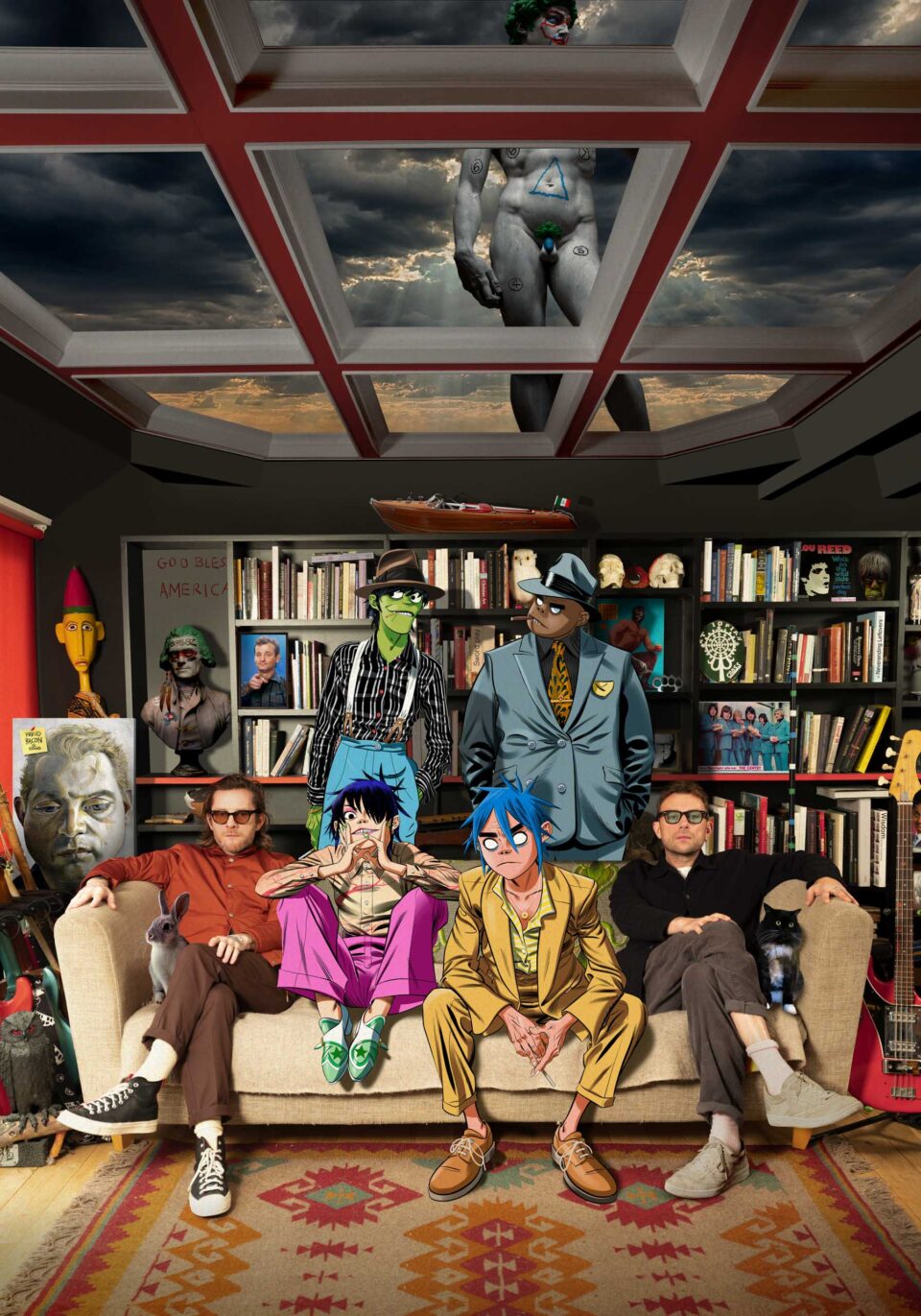

It was reported that Albarn and Hewlett had had a falling-out during this time (according to The Guardian, they didn’t speak for three years) because Hewlett was resentful that his contributions to Gorillaz had been diminished, with less emphasis on his visuals as Gorillaz’s massive all-star shows became more typical arena productions. But Albarn, who now lives on the opposite side of the English Channel from Hewlett, insists it was “not so much a falling-out. It was just a change of [life]. We were supposed to be doing something together, and then Jamie met [his wife] Emma [de Caunes, a French actress], and they fell in love. And he moved to France. We just had a moment in time where we were on different trajectories. But it didn’t last long. My relationship with Jamie is amazing. I’m very, very lucky to have him as a friend.”

And that brings us to The Mountain. “If the first record was the manifestation of our hedonistic cohabitation, and then the second record was sort of a reaction to 9/11 and the way the world had changed then, and then Plastic Beach was about the world that we’re bringing our kids into, then I think this record is the most cohesive since that time, because Jamie and I have spent so much time working on it together,” Albarn states. “We’re speaking exactly the same language again, visually and musically.”

“Moving forward, the way it works is we often go off on an adventure somewhere and an idea comes, and then it’s just conversations, with Damon sending music and me sending drawings,” says Hewlett. “And it just sort of grows from that. We’ve been doing it so long, it’s kind of like second nature now. The problem isn’t how to do it, but where to go to be inspired.”

Hewlett suggested India, one of the few countries that the well-traveled Albarn had never visited, even if Hewlett’s most recent Indian trip hadn’t exactly been idyllic. “I should have come back saying, ‘I’m never going anywhere near that country again! We’ve just had the worst experience of our life!’ But it actually worked the other way, because it was just such a fascinating place,” says Hewlett.

In late 2022, Hewlett’s wife and her mother were in India on an Ayurvedic medicine retreat when Emma’s mom had a stroke, and Hewlett rushed to be by their side. “We spent so long there, under quite traumatic circumstances, during a pneumonia epidemic in a public hospital in Jaipur, visiting every day, hoping she’d wake up from the coma. That was a hardcore experience. But I kind of fell in love with Jaipur at the same time,” he explains. “For me, visually, everything you see there is just mind-blowing. I came back incredibly inspired, and desperate to go back with Damon to see what we could find. I said to him, ‘We have to go into India to do the next album.’”

“If the first record was the manifestation of our hedonistic cohabitation, and then the second record was sort of a reaction to 9/11 and the way the world had changed then, and then Plastic Beach was about the world that we’re bringing our kids into, then I think [The Mountain] is the most cohesive since that time. We’re speaking exactly the same language again, visually and musically.” — Damon Albarn

“The thing is, this record emerged out of this kind of shared loss,” says Albarn. He and Hewlett ultimately embarked on two “classic Indian odysseys,” but in between those two excursions, both of their fathers died, just 10 days apart. Albarn, who’d always been into Indian music thanks to his parents’ fascination with ’60s Indian culture (“My early years were full of sitar music and incense”), actually scattered his father’s ashes on the Ganges river during their second visit. “And that ended up feeding into the narrative of the record—making a record about loss and death, but from the Hindu perspective, which is more about transition and transit,” says Hewlett. “Like, ‘I’m sad that I won’t see you again in this form, but I’m also celebrating the fact that you will be coming back. And I probably will never, ever find you, but you are coming back.’ I don’t know, there’s something about that. I said, ‘If we can make an album that makes death less scary for people, that would be a real achievement.’”

And that’s where Russel Hobbs’ supernatural abilities come in. “Because Gorillaz are cartoons, they can really do whatever they like, and one of Russel’s superpowers is he can summon the ghosts of dead musicians,” explains Albarn. “So that’s another aspect of the new record: found stuff from people we’ve worked with, who are no longer here.” For instance, one The Mountain track, “Moon Cave,” features audio of Trugoy. “The main narrator is Black Thought, and he talks to Dave. So there’s conversations between dead and living people.” The album also features “a whole new song with Mark E. Smith,” an unreleased freestyle by D12’s Proof, Tony Allen, Dennis Hopper, and of course, Womack. “It’s just nice, especially the ones I knew really well, like Dave and Bobby. It’s so nice hearing them. They feel so present,” Albarn says, smiling sweetly.

“One of the nice ideas on this album is that they’re speaking from the next place,” says Hewlett. “They’re joining us, but from somewhere else. I’m finding a way of interpreting that visually; I’m in the process of figuring out how to do that, appropriately and with respect. But working on this record, I actually feel less worried about death, for some reason. It doesn’t seem to bother me as much anymore. There’s still that voice in the back of my head that keeps saying, ‘You’re getting older,’ but now, I kind of don’t care. I feel released from that sort of inherent fear of the end. I feel good about things, through having this experience and going on this journey.”

Living The Mountain collaborators include 92-year-old Bollywood legend Asha Bhosle (“One of the biggest stars ever in India; she’s recorded something ridiculous, like 7,000 songs,” Albarn notes), Indian-American singer-songwriter Asha Puthli, Argentinian rapper Trueno, Smiths guitarist Johnny Marr, American Islamic scholar and civil rights activist Omar Suleiman with Yasiin Bey, IDLES’s Joe Talbot, songwriter and US National Youth Poet Laureate Kara Jackson, sitarist Anoushka Shankar, and more of “the most amazing Indian musicians.” Sparks also appear on lead single “The Happy Dictator,” a song not actually inspired by India, but by a trip Albarn took with his daughter Missy to Turkmenistan. “I was like, ‘This song is just screaming Sparks to me.’ Literally screaming Sparks,’” Albarn laughs. “It’s just a crazy, crazy, crazy record. Everybody’s there on this record. Some of the record is in Hindi, but there’s also a lot in Spanish and English. It’s a very rich record—part beautiful, part deadly, and part futuristic. It’s this huge, great fantasy about the afterlife and the Trumpian age.”

In that way, The Mountain is a companion piece of sorts to 2017’s Humanz. That prophetic album was recorded while Donald Trump was launching his first presidential campaign, and it imagined a dark future if Trump won the 2016 election—a possibility that still seemed preposterous at the time to many, but not to Albarn. “That entire record was about the imminent existential threat which has now become so manifest in America and has implications for everybody,” he says. “Everyone was still laughing at [Trump] then, but I was kind of like, ‘No, no, no, no, no!’ I was absolutely almost pinned to the floor with terror at the thought of it—not so much because of him, but because of the momentum. That attitude can engender in other people, because it’s a viral idea, isn’t it? He’s so viral.

“It’s everywhere, this weird sort of populism that’s based on misinformation and fearmongering, and it’s really depressing,” Albarn continues. “And it’s really difficult these days to stay in the middle ground, which is really the only place where you can have any kind of meaningful conversation, when both voices are being heard. I don’t have social media or anything like that, and I do get a bit angry with myself sometimes that I’m so mute. But then again, I’m terrified of entering the fray, really.” So, is he entering the fray with The Mountain? “I think so. In my slightly obtuse, slightly abstract, weird way.”

“There’s a whole generation of younger people who live through avatars and spend their days doing cosplay, and have almost turned their back on the real world. Because the real world is just so unbearable.” — Jamie Hewlett

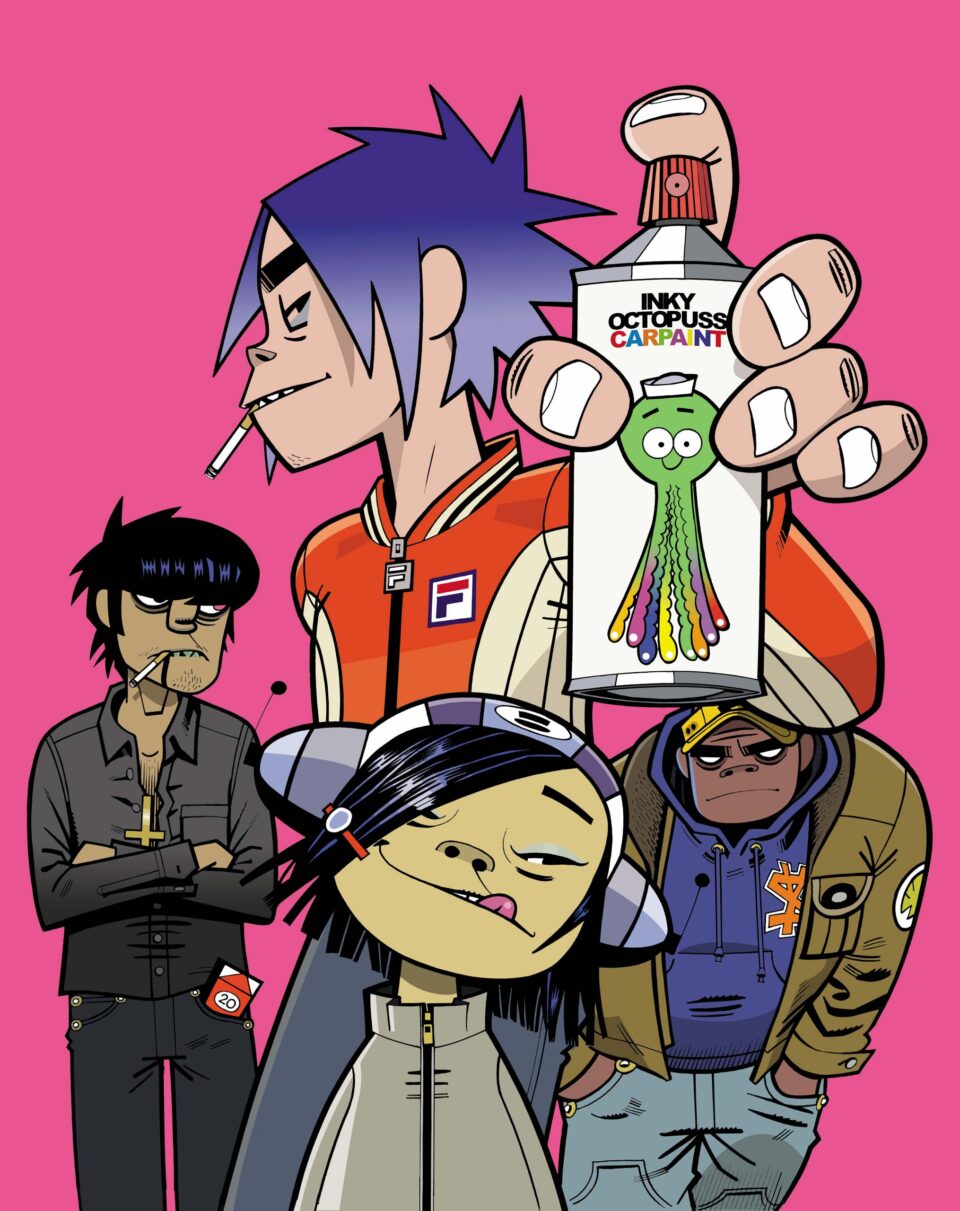

While Humanz may have predicted the unfortunate rise of Trump, Gorillaz have been prescient in many other, more idealistic ways. “I suppose we just wanted to create a world and see where it took us,” muses Albarn. “There’s always been an aspect of looking into the near future with it. I like to think that it’s a prophetic beast.” For instance, when Hewlett designed Gorillaz’s groundbreaking interactive website, “sort of a giant youth club online where everyone could meet,” way back in 2001, “the whole idea of a band living in a virtual world literally just didn’t exist,” Albarn points out. But he and Hewlett were already predicting in their early Yahoo interview that in the future, “People won’t go to concerts anymore. They’ll just spend their days glued to their computer screens.” Nearly two decades later, at the height of COVID lockdown, Gorillaz released their highly collaborative album Song Machine: Season One and triumphantly pulled off the greatest livestream concert of 2020 from Kong Studios when audiences didn’t have the privilege of experiencing live music.

And this year, Noodle, 2D, Russel, and Murdoc made their debut as virtual Fortnite Festival headliners. “Yeah, it sort of came true, for better or worse,” Hewlett chuckles. “There’s kids watching concerts in a computer-simulated world. They put their skin on, be whoever they want to be, and go to see concerts in the Fortnite world. Twenty-five years later, the importance of animated characters and avatars in our daily life has just grown and grown and grown. There’s a whole generation of younger people who live through avatars and spend their days doing cosplay, and have almost turned their back on the real world. Because the real world is just so unbearable.”

The visuals “allow an entry point for each generation,” Albarn theorizes, which is how Gorillaz have maintained their appeal during the 2000s’ fraught and fluctuating digital age. “There’s a lot of Gorillaz fans who were attracted by the animation, but then they really got into the music. And then, through the music, they were discovering De La Soul and Dennis Hopper and Bobby Womack and Ibrahim Ferrer, artists they maybe would never have discovered in their entire life,” says Hewlett. “In the last five years, we’ve worked with a lot of young artists who, when they arrive at the studio, say, ‘I grew up on Gorillaz. It blew my mind. It got me into music.’ On one hand, that makes me feel a little bit old. But on the other hand, it’s like, ‘Well, if we played a part in influencing you and sending you off in a direction, and you’ve arrived here, then that’s great.’”

Albarn still has a wishlist of future collaborators, including comedian Dave Chappelle, who he’d once envisioned appearing on De La Soul’s Humanz cut “Momentz” (“I’m still trying to engineer that; I won’t give up on that one”), and the elusive Kate Bush. “I really wanted Kate Bush to be on The Mountain. She kind of lives near me, and we’ve discussed having afternoon tea several times, but it’s never gone any further than that at this moment in time. Sometimes I just want to go ’round to her place and kidnap her,” he semi-jokes. And with Albarn and Hewlett’s brotherly bond stronger than ever after their shared The Mountain experience and House of Kong exhibition, they’re excited about the near future, which includes a complete relaunch of the Gorillaz website. “It’s been a really busy couple of years, putting all of this together,” Hewlett enthuses. “So, toward the end of this year and next year, there’s going to be a lot of Gorillaz activity.”

“Gorillaz has taught me that there’s literally nothing that you should place outside possibility when it comes to music… I think it works in every language, every time signature, every key, young and old. It’s very, very universal in that sense, and very kind of democratic.” — Damon Albarn

They’d also still like to make a Gorillaz movie musical or series, which has apparently been in talks for years, including most recently with Netflix. “The mad thing about it is, it’s a no-brainer! Literally since the first time we went to LA with Gorillaz, we’ve been in this kind of song-and-dance with movie companies,” says Albarn. But never say never: After 25 years, Gorillaz are really just getting started.

“You know, Gorillaz has taught me that there’s literally nothing that you should place outside possibility when it comes to music,” Albarn muses. “There are obviously certain moral guidelines that you wouldn’t want to trespass over, but I think it works in every language, every time signature, every key, young and old. It’s very, very universal in that sense, and very kind of democratic. And, it is genuinely exciting. Which is nice. I mean, I’m 57, and I'm still super-excited about making new music.

“And it’s always fresh drawings. All Jamie has to do is just get a new pack of felt tips, each time.” FL