2016 was a year in which the narrative got flipped on its head. At first it felt like what we would remember was the changing of the guard: There were so many notable figures lost that legends like Merle Freakin’ Haggard of all people were getting lost in the fray. But in November everything changed, and suddenly it almost seemed like some of those departed may have actually picked a great time to check out, if there ever is one. (Though it’s truly a shame we never got to see Prince tweet at @realDonaldTrump.) By the time people were making their 2016 year-end lists, it was clear that 2017 was going to be a much different type of year.

But the beat marches on. And album release cycles definitely do not stop for anything—especially when music can be of such service in either confronting the harsh reality of America in 2017, or escaping from it. Not all of these albums are political in nature—or even necessarily feel like any kind of reaction to the times whatsoever—but many do in one way or another. That judgment of tone has been, and will remain, the right of the artist. And just the same: Deciding what we keep with us—through the good years and the bad—is, and will remain, the right of the listener.

Presenting the best albums of 2017.

Listen along on Spotify.

25. The Courtneys — II

2017 has been a long year, so you’d be forgiven for forgetting that Japandroids put out an album in January. It was pretty good. But it wasn’t even close to the best album of the year in that style: big-time, hook-laden, highway-worthy rock. That honor goes to The Courtneys, who casually released one of the catchiest albums of the year—while still retaining the murky worldview established on their 2013 debut. The modestly named II shoves you into the back of the Vancouver trio’s presumptive AMC Pacer, and heads for nowhere in particular. It’s a glossy blur of octave riffs and gently shouted lyrics about VHS-era movies (The Lost Boys, Mars Attacks!) and how much of a bummer it is to love, even though you know you wouldn’t have it any other way. — Nate Rogers

It’s fitting that Slowdive’s first album in twenty-two years is obsessed with time—the way it paradoxically constricts and expands, how moments are held crystallized in it. Fitting, too, that the first song on their first new album in twenty-two years is called “Slomo,” a shoegazing mosaic of twinkling guitars, notes spackled starbright against a backdrop of shadows, obscuring an untold multitude of universes. Rachel Goswell’s vocals are as transcendent as ever, rich with texture but still intimidatingly inhuman, and meanwhile Neil Halstead somehow sounds as if he’s gotten younger. “Star Roving” pulses with careful vitality, while “Don’t Know Why” bears the same sonic distance and overwhelming size last identically heard on 1995’s Pygmalion. Later, “Sugar for the Pill” builds to a plateau from which “Falling Ashes” jumps, drifting to earth in bits and scraps within which are clasped whole worlds, whole albums that could have been existing on timelines that never were. It’s as if no time has passed at all. — Dom Sinacola

Orc sees John Dwyer experimenting with a new writing formula following the lukewarm reception of his band’s recent prog-rock-tinged endeavors: appeasing his audience of riff-thirsty Dwy-hards with two of the most potent bouillons concocted over the course of the revolving cast of Sees’s decade long career, leaving them reeling while he and his band venture into uncultivated cosmic territories. What follows, however, is just as engaging as his blitzkrieg prelude, leading the listener through the hazy krautrock and heavy psych of the album’s superb forty-minute denouement. Despite Orc’s unsubtle change of pace midway into the eight-minute “Keys to the Castle,” the atmosphere remains undeniably Seesian despite the gurgling Wurlitzers, versatile Mellotrons, and surplus of lyric-less tracks. While Orc demonstrates the extent to which Dwyer can get lost in his own imagination, the three-minute solo by drummers Dan Rincon and Paul Quattrone that closes the album suggests the Oh Sees project is still far from a solo endeavor. — Mike LeSuer

22. Miguel — War & Leisure

My mother used to tell me the ’70s and ’80s were “just a much sexier time for music than now.” Once I moved past the awkwardness of that recurring exchange, I realized how accurate she was—sure, we’ve still got plenty of sexuality in pop, but sex in music from male artists these days can often feel more like an obsession than a celebration. Who today matches the sex-positive male energy of a Prince, a Rick James, a Marvin Gaye, like Miguel?

“That’s the one thing I’ve never done, to kind of just focus on making people feel good,” Miguel said in in his cover story for FLOOD’s latest print issue. His albums in the past have dealt much with frustration and heartache, but this year he’s shifting the subject to pure joy with his contagious grin and Herculean vocal range, in a time when we need so badly to feel good. And that’s not to deem this record escapist either—the album sounds politically avoidant at first, but really War & Leisure delicately confronts misogyny, gun culture, and even the hypothetical leveling of Los Angeles through lenses in which love simply overcomes. — Jamie Lawlor

Click here to read our feature with Miguel and Pussy Riot.

21. The National — Sleep Well Beast

Few bands can do melancholy like The National. Much of that comes down to Matt Berninger’s vocal delivery, which is weighed down by a sense of existential dread but, at the same time, too bummed to care about that same dread. Musically, though, the band have expanded their sound, turning in twelve songs that glower with a tight-knit lethargy and despondency. There are more flairs and flourishes in the layers of these songs than ever before, but it remains, at heart, a record by one of the most astonishing rock bands in the world right now. Songs like “Day I Die” and “Dark Side of the Gym” recall the band they’ve always been, while the bleeps and electronics of “The System Only Dreams in Total Darkness” and “I’ll Still Destroy You” find them venturing into new musical territory, bold and unafraid—but still just as poignant and poetic as ever. — Mischa Pearlman

20. The Clientele — Music for the Age of Miracles

Most of The Clientele’s music could be categorized as being out of time. There’s a constant sense of place, yes, but in the London of Alasdair MacLean’s nylon-string melodies and cobblestone lyrics, Ray Davies is just as likely to walk by as Charles Dickens. And yet, his group’s latest is called Music for the Age of Miracles, as if this album is particularly for us, right now (and even more ridiculous, as if this current era could be known as an Age of Miracles). Whoever, or whenever, it’s for, however, it’s lovely—and it’s as intoxicating as any LP in the Clientele discography. “This is the year that the monster will come,” MacLean warns on career-highlight “Lunar Days,” and, at least in the US, he’s proven to be right. But miracles aren’t going to define a generation until it was at first defined by a lack of them. — Nate Rogers

19. Vince Staples — Big Fish Theory

Summertime ’06 took stock of Vince Staples’s Ramona Park roots via brimstone beats, barging through the concrete blocks of his memory like Being John Malkovich’s titular character chasing meaning through the dorm rooms of his own mind. Follow-up Big Fish Theory turns uneasily away from the past, witness to the emcee’s transformation into a reluctant futurist aided by Detroit techno (producer Jimmy Edgar on “745”) and ambassadors of remix nation (Flume and SOPHIE helming “Yeah Right,” the K. Dot–abetted album highlight). This is the derogatory designation of “urban” music made literal, Staples’s slide-and-somersault flow paired with club beats reflecting not just the stomach-churning industrialism of modernity, but also the commodification of the same, which he simultaneously bucks against. In “Homage,” laced together by metal spiderwebs and Berlin-esque weirdness (produced by Zack Sekoff, Staples’ most prominent album partner), Staples spits, “Hitchcock of my modern day / Where the fuck is my VMA?” If this is what hip-hop should sound like in 2017, that’s only because Staples questions every word of what that even means. — Dom Sinacola

Click here to read our feature with Vince Staples.

18. Craig Finn — We All Want the Same Things

For his third solo record, Craig Finn has shifted even further away from The Hold Steady. Instead, he’s created an album that recasts his narrative lyrics within more atmospheric and experimental tunes that seem to serve more as mini-soundtracks than rock and roll songs. The most obvious example—and one of the album’s best songs—is the forlorn, spoken-word road trip of “God in Chicago,” which is about as cinematic as it gets. Eleven years on from Boys and Girls in America, this album once again cements Finn’s talents as a songwriter—not just in terms of his storytelling abilities, which remain as potent as ever, but also as a chronicler of the American experience and the people struggling to live ordinary lives in ordinary towns. The irony, of course, is that Finn makes those lives just as interesting as anything in the movies. — Mischa Pearlman

17. St. Vincent — MASSEDUCTION

Annie Clark’s St. Vincent project has become the examination of a spectacle. From the pre-release “press cycle” to the one-woman tour-de-force live show that plays as much like a theatrical performance as it does a concert, MASSEDUCTION is a critical look at celebrity and fame through the prism of the artist’s own struggles with love and loneliness—in part brought upon by the success of the St. Vincent project. While all of Clark’s records are pushed by a philosophical bent, the sheer pop genius of her persona allows for the music to take the intellectual rigor down a notch, even when she’s musing on cultural topics, like our debilitating reliance on various substances—legal and otherwise (“Pills”). It’s rarely during such moments of societal analysis that MASSEDUCTION is at its best, though. Rather, it’s during moments of heartbreaking intimacy that the album stands as one of Clark’s finest works to date. “Happy Birthday, Johnny” is perhaps the most beautiful song she’s ever written; it’s a tender and broken ode to a friend or relative or lover who’s succumbed to a life of homelessness due to addiction. “New York” tells the story of a lost love, and of how such a relationship skews the way we view home. MASSEDUCTION is an album attempting to hit everything, but it stands strongest when focusing on small moments universal in their loneliness. — Will Schube

16. John Andrews and the Yawns — Bad Posture

John Andrews lives in a large colonial house, some several-hundred years old, in a place called Mount Misery. It sounds like a joke, but apparently it’s not: The very real spot is in Barrington, New Hampshire, and it’s where he recorded Bad Posture—an album for which “misery” would not at all be an appropriate state of mind to place it in. Overall, it’s more of a joyous record, in fact, even though it is still tinged with a sense of shrugged detachment that you might expect from someone living in relative isolation. Andrews, who’s known for his multi-instrumental work in Quilt and Woods, touches up these songs with an endless bag of tricks—fuzz guitar lines, rolling drums, organ solos. He’s Levon Helm one minute, Richard Manuel the next, playing all the parts needed to paint a full picture of life on the hill—even if it is a bit miserable sometimes. “That mountain gets taller each time I climb it,” he laments on “Windmill,” and you’re glad that he continues to do so nevertheless. — Nate Rogers

15. Open Mike Eagle — Brick Body Kids Still Daydream

2017 was undoubtedly the Year of Disclosure, with the suckiest white people theatrically confirming that the “great” they’re referring to is, in fact, the worst, and an entire gender of humans coming forward to reveal the extent to which their work lives have been afflicted with sexual assault. With both of these events coloring the musical zeitgeist with a furious shade of #MeToo, Open Mike Eagle’s Brick Body Kids couldn’t have landed at a better moment. The LA rapper, who delivered the line “When I pass gas it sounds like a fax machine” on his previous solo effort—and braved the snakes and mousetraps of Rapper Warrior Ninja in the interim—returned to his native Chi Town to track down the villain who demolished the Robert Taylor Homes on the city’s South Side, formerly home to much of his extended family. Reprising his role as preteen Michael Eagle, Open Mike raps bits of the album from the perspective of Iron Hood, an identity constructed during his childhood to confront the hyperbolic machismo of his neighborhood (“I ain’t cried since ’94 or something!”), while closing the record with a vengeful attack on American inequality (“They say America fights fair / But they won’t demolish your timeshare”). Despite the comic personality Eagle’s built for himself as a musician, Brick Body is easily his most revealing album yet. — Mike LeSuer

Click here to read our feature with Open Mike Eagle.

14. Randy Newman — Dark Matter

On his first studio album in nearly a decade, Randy Newman includes only nine songs, one of them a rehash of his 2003 theme song from the show Monk. If that reads as anticlimactic, be advised that Dark Matter opens with one of the most ambitious songs of his career—an epic piece of theater, featuring contrasting musical modes and a variety of perspectives, full of humor, self-deprecation, satire, and speculation on the existence of God and the limitations of science. While you’re at it, you might also note that the new version of the Monk theme features a side of Newman he seldom showcases on his own records—the giddy orchestra leader, hamming it up as he runs through all the sounds and colors of his big band.

In other words: Not a toss-off. In fact, Dark Matter is as sophisticated as any Newman album since Good Old Boys, its biting humor tempered by weathered humanity and hard-won wisdom. “Brothers” is a song about Jack and Bobby Kennedy, about the Cuban Missile Crisis, about hubris, about Celia Cruz—but mostly, about brothers; and “Putin” is a song about Putin, yet it’s most noteworthy for how it showcases a satirist never content with the obvious laughs, and an arranger who knows well the nuance of pomp and circumstance. On one song after another, Newman’s still got it. — Josh Hurst

This year saw several of Ty Segall’s contemporaries (and bandmates) swapping their feedback-driven discographies for more calculated songwriting endeavors. Although his second shot at a self-titled record is undeniably tidier than the shitgaze of yesterdecade, Segall’s unequivocal yen to shred outweighed another laudable stab at going straight alongside his peers.

“Baby’s gonna break a guitar / Gonna make it a real big star,” an imperceptibly aged Segall recites sardonically on the opener, conceivably recalling his own aspirations around the time of his first self-titled. But even reciting these lyrics, Segall can’t help busting out a riff likely to dismember his Fender. Moments later, the saloon piano on “Talkin’” sets a smooth scene before being razed by the subsequent wailing guitars on “The Only One” and shattering dishes (or is it toilets?) on “Thank You Mr. K,” while the epic “Warm Hands”—comprising over a quarter of the album—relentlessly drives home the point that garage punk is more than a mere phase for the tricenarian riffer.

The self-titled record being nature’s do-over for any recording artist, Ty represents a clean slate for Segall, repurposing only the most necessary moments from his past solo work and collaborations to the congealed present, where Sleeper’s acoustic lullabies cohabitate (albeit submissively) within a tracklist with Slaughterhouse’s caustic attitude. — Mike LeSuer

Click here to read our feature with Ty Segall.

12. LCD Soundsystem — American Dream

If you grew up attached to LCD Soundsystem, you probably understood and defended James Murphy’s sudden retirement in 2011—the ultimate sacrifice in the name of indie integrity. If so, you probably also felt an eerie mix of elation and betrayal when the full resurrection was announced. But one thing you knew no matter what was that James Murphy wouldn’t just announce a fourth album unless it was exactly what you yearned to hear for half a decade.

American Dream has Murphy at his lyrical peak, one of his more underrated strengths. Take for example the line “It moves like a virus and enters our skin / The first sign divides us, the second is moving to Berlin,” likely a double entendre honoring his late friend David Bowie and also skewering America’s Eurocentric post-election grandstanders. Plus, how many other albums in 2017 are this shit-kicking live? (If you haven’t seen the show, there may be a few dozen more Brooklyn dates left.)

And let’s be honest: This year needed an LCD album more than any. Murphy is like the consummate anti-Trump: the New Yorker that lets his hair go grey and sings his fear of aging for the world to hear instead of masking it, nakedly mourning losses over an old synthesizer rather than barking superlatives over a podium; “You’re waking a monster that will drive you from your hoary holes of gold,” he sings on “Call the Police.” And to think we thought he was just going to sit back and watch the young curmudgeons go on without him. American Dream is proof that if any withdrawn musician can make another great album, they will make another great album. Call it James Murphy’s Law. — Jamie Lawlor

11. Kevin Morby — City Music

On City Music, Kevin Morby is the time-lapse camera slowly tracking the bustle of city dwellers running to and fro, again and again. Morby is the impartial observer, treating urban sensibilities with an unflinching and sympathetic eye. Having lived in New York, then Los Angeles, and now returning to his hometown of Kansas City part-time as well, Morby is more than able to step in as the poet emeritus of life as a city dweller. “City Music,” the album’s title track, is a song for the cacophony of city sounds coming together to create something bigger and more beautiful than noises conjured in isolated loneliness.

“Oh, that city music / Oh, that city sound / Oh, that city music / Oh, it’s coming ’round.” Perhaps, in this sense, City Music isn’t Morby’s “city” album as much as it’s a story of a moving life; not quite transient but not willing to stick anywhere for more than a few months. While City Music does play as a distinctly New York record at times, he also pays homage to Los Angeles, covering “Caught in My Eye” by Germs. The pairing of Morby and a hardcore punk band may appear incongruous, but his attention to detail and intimate look at the original allows his version to shine alongside it. The track is a nice summation for the album as a whole: quieter than the subject it’s tackling, but mountainous in its achievement as a whole. — Will Schube

Click here to read our feature with Kevin Morby.

10. The Peacers — Introducing the Crimsmen

Since Sic Alps broke up in 2013, Mike Donovan has found himself somewhat removed from the public eye. It’s not like his band was ever a household name, but they were central to the late 2000s San Francisco garage rock scene that made such an impact before crumbling to the subsequent tech boom in the early 2010s. (In retrospect, the writing was always on the wall for a garage rock movement located in a city in which no one actually had a garage.) Fellow scene-leaders John Dwyer and Ty Segall counted their losses and migrated to LA, but Donovan stayed put. And then, somewhat ironically for someone living in the shadow of Twitter, Donovan decided to stay away from the social media game that dictates so much nowadays, effectively self-exiling his new band, The Peacers.

For fans who haven’t stayed in touch (maybe try writing a letter next time), that was a mistake. Both of the first two Peacers albums (2015’s self-titled debut and this year’s Introducing the Crimsmen) have been landmark releases—boiling outsider rock with a bizarrely coherent arena-sized twist. On Introducing the Crimsmen, Donovan and his group of SF holdouts—Shayde Sartin, Mike Shoun, and Bo Moore—play like survivors surveying an apocalyptic North Beach alongside Gregory Peck. But however burnt out that landscape may be, there remains an air of lightheartedness throughout, with Donovan at one point casually tossing off the best song about being lazy since R. Stevie Moore wrote the book on it in 1986. The Peacers know that rock and roll doesn’t pay the bills like it used to, but in a city where nobody can pay their bills regardless, you might as well give the people something to listen to while everything goes up in smoke. — Nate Rogers

9. Courtney Barnett and Kurt Vile — Lotta Sea Lice

An album that sounds this lived-in, this warm and welcoming, couldn’t possibly be counted as a lark; its architects worked hard to make it sound this ragged and tossed-off, remembering that vibe alone is no substitute for strong songwriting. The result is an album that’s surprisingly tuneful, propulsive, and direct for two singer/songwriters who are often labeled, rightly or wrongly, as “slackers.”

Their aesthetic of choice is an appealing one: Their twin guitars intertwine to give the album a gnarled, brambly feeling, while the songs themselves are gracefully unhurried and disheveled. Courtney and Kurt trade deadpan verses that are rich in oddball humor but also in real, heart-on-sleeve humanity; listen to how the unfussy nonchalance of lead track “Over Everything” hides some moving confessions about the need to find shelter from the storm—in music, in friendship, in good-faith collaboration.

It’s not the only song to adopt a self-motivational tone, either; much of Lotta Sea Lice sounds like the pep talk you give yourself in the mirror at the start of a new day. So for as wonderfully accidental as this entire album seems, don’t call it a throwaway: These kindred spirits psyched themselves into an album that’s as slyly ambitious and off-handedly hopeful as any of their solo works. They bring out the best in each other. — Josh Hurst

8. Sheer Mag — Need to Feel Your Love

Nobody listens to EPs anymore. At least, that’s how it seemed before Sheer Mag leveled the landscape with three of the best EPs released in recent memory, calling back an era in which the likes of Mission of Burma and Minor Threat made career-defining statements as fifteen-minute flash-in-pan upper-cuts. The compilation of Sheer Mag’s initial EPs—titled, er, Compilation—from earlier this year cemented their arrival and set the scene for a traditional debut with massive expectations. No pressure, though: It was only the entire fate of a nearly dead-and-buried hard rock scene that was hanging in the balance. (Or something like that.) And what did these Nuthouse-livin’, major-label-dismissin’ Philly punks do? They went and made one of the most hard-hitting albums in recent memory.

Need to Feel Your Love is unmistakably Sheer Mag—Tina Halladay’s voice and Kyle Seely’s riffs could never be dialled back that much—but it’s also a new era for the group, one which finds them embracing a vulnerably clean-sounding production and an increasingly ambitious set of arrangements. Lightning-fast and relentless, it’s a big-time record—you know, like the ones the industry used to churn out before the money dried up? As if by way of unabashed declaration, Halladay greets us, on opener “Meet Me in the Street,” with an honest-to-god Daltrey howl, just putting everything she has into it, while Seely, not to be outdone, finger-taps underneath, the power-stance practically visible just in listening to it. In so many hands, it’s a record that would fall hopelessly flat, corny and out of touch. But in Sheer Mag’s hands, it’s more than just a throwback—it’s a resurrection. — Nate Rogers

7. Mavis Staples — If All I Was Was Black

Mavis Staples inhabits everything she does with full-bodied joy—faith and good cheer as matters of intention, all the more defiant when times get tough. And they have been plenty tough in the first year of the Trump presidency, something Mavis reckons with eloquently and unmistakably on If All I Was Was Black, the third of her collaborative winning streak with songwriter and producer Jeff Tweedy of Wilco.

Here he furnishes her with songs of hard-won hope—bridge-building music in an era where walls are all the rage, and lionhearted expressions of humanism during a time when humanity seems in short supply. They are great songs, but not primarily because of how they address the present; their power is rooted in the past, with Tweedy drawing inspiration from R&B’s great message-music tradition, from gospel and heady funk, and even from country and Americana. The unspoken suggestion here is that American music contains multitudes; its imagination can’t be fenced in. Mavis delivers it all joyfully. No one bests her at weaponizing empathy and inclusion—and on If All I Was Was Black, her aim is true. — Josh Hurst

6. Spoon — Hot Thoughts

If 2017 was a year for veterans—for bands and artists releasing their umpteenth albums, or coming back after long breaks, in every case sounding both refreshed and revitalized—then the men of Spoon, on their ninth LP, have simply continued to wield their reliability as they always have: like goddamn pros. They weren’t playing “Hot Thoughts” on Ellen because they had to sand the rough edges from their brittle, bone-chip pop in order to appeal to people who prefer their riffs less staccato and their swagger less stabby—they were on Ellen because Ellen is in love with Hot Thoughts, her

desire for it palpable on her daytime show, and whenever one listens to Spoon—any

Spoon—one understands Ellen’s thirst. “Do I have to talk you into it?” Britt Daniel lasciviously asks on the album’s third track. Later: “Can I sit next to you?” He already knows how we’ll respond; everything he says seems lascivious.

Which is to say: Hot Thoughts may be the first Spoon record to double down on seduction as an end unto itself. Radio-ready “First Caress,” a kissing cousin to “The Way We Get By,” steams up as Daniel blurts out, “And when you say the wrong thing / I know I hear the right thing / I know it’s just the same,” which would sound creepy were Spoon not pursuing sexiness as entelechy. “Pink Up,” weightless but lush, furthers that connection to 2002’s Kill the Moonlight, bearing the same wandering experimentation and avant-airiness, navigating the same sinister notions that seem to accompany any music Spoon makes that isn’t punching through each speaker. Hot Thoughts, then, is what we should and will always expect from Spoon—an elemental collection operating in urges, just like the last record and the one before, if you can keep them all straight. It hardly matters: Hot Thoughts has intoxicated us—like that’s its job. — Dom Sinacola

Click here to read our feature with Spoon.

5. Charlotte Gainsbourg — Rest

Those who’ve suffered an acute loss know that after the funeral, the life around you moves on. Friends go back to work, distant relatives return home and you remain suspended in the fabric of mourning—its emotional wax and wane, the upended routines, a healed scar or stealthy puncture wound with each new day. It’s isolating, and seemingly unending. Charlotte Gainsbourg’s fourth solo LP was created in grief’s white knuckle grip. Her half sister Kate Barry fell from her apartment window in December 2013, a death that was presumed a suicide. Shortly after, the French actress and musician escaped to New York to elude the shadows that followed her in Paris, where she hunkered down with French producer SebastiAn for a year of writing and recording.

Rest’s lyrical intimacy and cinematic instrumentation meet as two sides of grief’s coin, presenting the unpredictable, revelatory, and melancholic turns in the healing journey through loss. Its orchestral flourishes, dramatic synthesizers, and driving bass lines slide easily into ears, as Gainsbourg’s breathy bilingual singing and philosophical lyricism builds a lump in the throat. It’s a fine melding of art pop and a poet’s deep cuts, the ease of which demonstrates a mastery of craft and emotional attunement. Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking comes to mind, a similarly affecting chronicle of the palpable sorrow in death’s wake and the caustic absurdity of the things we do to deal. With Rest, Gainsbourg loses herself (“Dans vos Airs”), picks herself up (“Sylvia Says”), and reflects (“Lying with You”). She’s heartworn and hopeful. On its surface, it’s an exquisite pop record—attention-grabbing and extremely listenable. Reach into its depths, its profondeur émotionnelle, and it’s a bombshell. — Erin Osmon

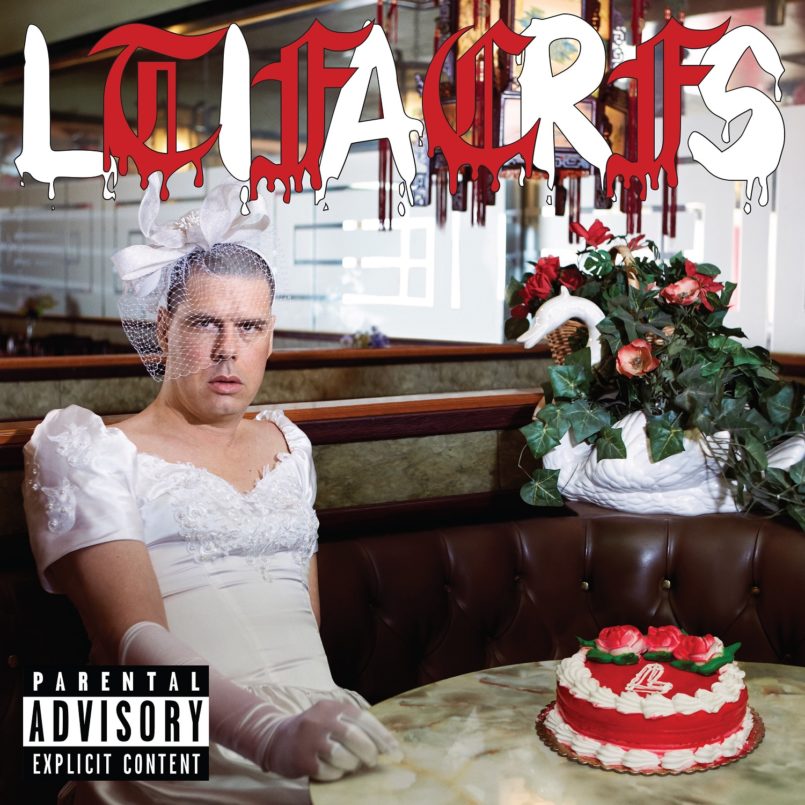

4. Liars — TFCF

Angus Andrew has given a few reasons as to why he’s wearing a wedding dress on the cover of Liars’ eighth album, TFCF (short for Theme from Crying Fountain). More recently, he’s used the cover to pledge his support for marriage equality (“It’s surprising and a little disappointing to me that a man wearing a wedding dress in 2017 would garner so much attention,” he said last month), but earlier in the press cycle, he bluntly explained it as being reflective of the end of his musical marriage to founding member Aaron Hemphill, who left the group following the release of 2014’s Mess. “The record is basically the theme music for our creative relationship deteriorating,” he said during a July AMA session on Reddit. He then answered the second part of the question, which was regarding the fate of another prop featured on the cover: “I ate the cake!”

In a sense, TFCF is Andrew figuring out a way to have his cake and eat it, too. Using the Liars name as a solo vehicle for the first time—and recording a Liars album in his home country of Australia for the first time as well—he had no one to consult but himself, with the result being a record unlike any in the band’s discography. That’s been said of pretty much every other Liars album in the past, but this one really does mark a larger sea change overarching a history of smaller ones, the music carrying with it the same type of fuck-it-we’ll-do-it-live attitude that McCartney invoked for McCartney II. On that note, album standout “Cred Woes” does indeed sound like a demented cousin to “Temporary Secretary”—that is, until it turns a heel in the bridge and slips into a quintessential Liars mantra for outcasts and weirdos everywhere: “I like to say when kids are calling me out that they should follow my footsteps instead of foolin’ around.” Single life is grand, ain’t it? — Nate Rogers

3. Kendrick Lamar — DAMN.

How does Kendrick Lamar feel? “I feel like it ain’t no tomorrow, fuck the world / The world is endin’, I’m done pretendin’ / And fuck you if you get offended,” he answers in the aptly titled “FEEL.,” the track’s genus a declaration, unmitigated, as if each all-caps song, each a sentence unto itself, is a bullet point hanging under the headline of Kung Fu Kenny’s soul. Elsewhere, he provides an exultant rebuttal: “Loyalty, got royalty inside my DNA,” imbuing Mike WiLL Made-It’s suffocating trap jingle with duty, a purpose which declares, “And I’m gon’ shine like I’m supposed to, antisocial, extrovert.” Whereas To Pimp a Butterfly was a presidential favorite of 2015, and untitled unmastered. was the empirical lark made from the goodwill of its predecessor, DAMN. is Kendrick in between, exploring that contradictory core, coy and blunt and brash and blisteringly aware. It’s the antisocial extroversion of a man who proudly takes on the burden of his community—“This is my heritage, all I’m inheritin’”—while struggling with the depression that encourages him to disregard the life so many in his community look to as inspiration.

The real irony of DAMN. is that it’s so saliently fun to behold, with sinuous beats so lithe they’re practically pluckable, with articles of unexpected melody (“LOVE.” is especially sweet) punctuating kaleidoscopic boom bap (“XXX.”) and apocalyptic screel (“HUMBLE.”), not to mention simmering funk (“LUST.”) over which the Dungeon Family would comfortably squat. Regionally, DAMN. spreads out, but Kendrick never seems interested in speaking for those all over the country who might consider him a voice for those without one—he only wants to synthesize those voices through his wonderfully ruffled timbre, to make their sounds visceral and their messages personal. Which is why DAMN. sometimes feels at odds with itself: It is an essential record (a future classic) concerned simply with essentials (beat, vocals, weird synth lines)—a concept album with no clear concept except for how to best shed one. How does Kendrick Lamar feel? The better question is: How do you? — Dom Sinacola

2. Alex Cameron — Forced Witness

2017 was either the best year for Australian musician Alex Cameron to release Forced Witness—his anthology of men behaving really, really badly—or the worst. He couldn’t have known, of course, that the downfall of Harvey Weinstein would kick off a long-overdue domino effect leading to the removal of numerous male sexual predators in positions of power and influence. Or could he?

It’s not as if Cameron is some Nostradamus specializing in perverts, but if you’ve been paying attention, you know that he’s been fleshing them out and exposing them for what they are on his records. Last year’s Jumping the Shark (itself a several-year old reissue) was full of seedy, pathetic characters, and you almost pitied them. On Forced Witness, however, the title tells you exactly what you’re in for. You’re lured in by production from Jonathan Rado of Foxygen, Angel Olsen’s vocals, and songwriting credited to Brandon Flowers. Then, suddenly, you find yourself in the company of a guy who feels “like Marlon Brando circa 1999” and thinks that that’s a good thing, and another who proclaims, “I got shat on by an eagle, baby, now I’m king of the neighborhood,” and another who explains, “There’s blood on my knuckles ’cause there’s money in the trunk.”

Luckily, the worse the subjects of Cameron’s songs are, the better his music gets. The aforementioned delusional gentleman is featured on the track “Marlon Brando,” and his gross bravado is backed by such talent that it almost seems earned. The guy with the bird shit on him is from “Stranger’s Kiss,” Cameron’s duet with Olsen and one of the most beautiful songs of the year. The bleeding guy narrates “Runnin’ Outta Luck,” which was co-written by Flowers and arrives with the synth-y Vegas glitz of the best Killers songs. Roy Molloy, Cameron’s horn player and co-conspirator, closes the track with some of the most tasteful sax since Roxy Music.

If, at record’s end, you’re left with doubts about Cameron’s true motivations—understandable, since he makes an awfully convincing creep—watch the video for closing track “Politics of Love,” which features the album’s credits as a text scroll. In a list of thank-yous, the final one is this: “And all the strong women who keep making their way into our lives and showing us what it means to be real men.” As our work continues into 2018, Cameron and Forced Witness will be right there in the trenches with us. — Lydia Pudzianowski

Click here to read our feature on Alex Cameron.

“My brain is like an orchestra / Playing on, insane,” Adrianne Lenker sings on “Mary,” the penultimate track on Big Thief’s second album Capacity, the line giving us warning of what’s about to come next. Perhaps the most ambitious song she’s written to date, “Mary” soon slips into what can only be described of as gorgeous word-vomit—the lyrics coming out at such a rapid and steady clip that Lenker is literally gasping for breath, thoughts and images spilling out, a whole world swirling around without a specific point or care, nothing deliberate, everything important. “The sugar rush / The constant hush / The pushing of the water gush.” It’s a cram-worthy chapter in the textbook of life that Lenker is working on with the rest of the band—Buck Meek on guitar, Max Oleartchik on bass, and James Krivchenia on drums—but it’s a textbook for one of those hippie classes without grades. In the end, everyone passes, one way or the other.

It’s this play between detached existential shrugging and dire, high-stakes wailing that makes Capacity such an overwhelmingly compelling listen. In a year that felt so hopeless—an entire country forced to reckon with its most deeply embedded and immovable prejudices during each passing day—it’s been tough not to lose sight of the beauty that nevertheless persists within the complexity of the human condition. Across forty-two minutes of music, Big Thief have provided a work that serves as a reminder of that fact—and a reminder that trauma can, in time, manifest itself in character-defining ways that are unimaginable at its onset.

In part, that’s what’s going on in the album’s knockout lead single, “Mythological Beauty,” in which Lenker recounts a childhood accident that almost killed her, when a railroad spike fell from a treehouse in the backyard, cracking her skull open. “I was just five and you were twenty-seven,” she sings, referring to her mother, “Praying, ‘Don’t let my baby die.’” As she tells it—and as the band cinematically sets the scene—the incident goes from being about something that happened to Lenker to being about something that happened to her mom—to being about how terrifyingly young twenty-seven is to be dealing with that type of emotional stress. Lenker switches gears mid-verse, going from a whisper to a yell, the lead guitar matching the transition with a swell itself, the bass and drums holding steady, making sure there’s something there for you to hold on to.

Of course, all this isn’t to say that there always has to be a silver lining. For instance, if you’re looking for something to take away in “Shark Smile,” a Springsteen-ian road drama with lyrics worthy of Nebraska, it’s that life is fleeting, and that guardrails (and railroad spikes, for that matter) hit quick. And that’s important to acknowledge, too. Sometimes the lesson in these songs is that life is always standing by ready to take the rug out from underneath you just when you least expect it. But if you can get up, you will. — Nate Rogers