In July, after a man named Micah Xavier Johnson killed five police officers in Dallas, Jonathan Chait sought to calm the readers of New York magazine by insisting that 2016 “is not 1968.” Despite everything that’s happened since, Chait’s contention that “the old, tattered idea of unity may be healthier than it seemed” is still somewhat sound, if you trust the popular vote to mean anything. But it’s telling that he felt the need to make the argument at all: we were only seven months in and 2016 was already being compared to one of the most tumultuous years in American history.

When we think of 1968, we don’t tend think of the music, because when the civilized world is in peril, music hardly seems to matter. Nevertheless, that year saw the release of The White Album, Astral Weeks, Beggars Banquet, At Folsom Prison, White Light/White Heat, Bookends, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, Music From Big Pink, I Heard It Through the Grapevine, Mama Tried, Otis Redding’s In Person at the Whisky A Go Go, Miles Davis’s Nefertiti, John Coltrane’s Om, The International Submarine Band’s Safe at Home, Desmond Dekker’s “Israelites.” Fleetwood Mac, Randy Newman, Silver Apples, Os Mutantes, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Neil Young all made their debuts. Brazil responded to its own political crisis with Tropicália. Nina Simone responded to ours with ’Nuff Said. Johnny Cash married June Carter.

Some of that music was engaged with the political moment; most of it was not. But it was all made in a time not unlike ours, when what remained of the social fabric seemed to be rending. This year, as with 1968, our best musicians actively pushed against oppressive forces, tested the boundaries of their genres, or just helped us find new ways to dance. Each is a way of refusing to be overwhelmed by the encroaching darkness. There’s no telling what 2017 has in store for us—outlook: not so good—but as the music of 2016 showed us again and again, power takes many forms; there are always new ways of fighting back.

Presenting the best records of 2016.

25. Margo Price — Midwest Farmer’s Daughter

“All I wanna do is make something last,” sings Margo Price on a country-pop epic called “Hands of Time” that could very easily outlast us all. The whole record is full of crumbling sand castles and dreams deferred, battles waged and frequently lost, things falling apart. Many of her characters feel like rural American versions of Ozymandias, striving for eternity even as time threatens to erase them. What makes the record powerful is how it harnesses tropes and tradition to lend grit to its ephemeralities. Price writes prison songs, divorce songs, revenge songs, drinkin’ songs, country songs, soul songs—the kinds of songs that have been around forever, drawn from wells that just get deeper as the years roll by. Similarly, years of hard knocks have left her tough and tender in equal measure: it’s possible that no country record in recent memory has had this many middle fingers in its lyrics, and that no record in any genre provided more laughs this year. — Josh Hurst

24. Cass McCombs — Mangy Love

Finally, a Cass McCombs record you can dance to! And by dance, of course, I mean “sway back and forth sloppily to while reading Urban Dictionary and sipping Fernet,” duh. For over a decade, Mr. McCombs has been as consistently great as anyone in the “indie” singer-songwriter cage, and Mangy Love offers perhaps a little more strut and jive than anything heretofore in the Cassalog. It’s still mostly the same mix of trippy weirdo gorgeousness we’ve come to expect, and on numbers like “Opposite House” and “Run Sister Run,” that newfound discernible groove purrs along like a calypso band playing an art school frat party on your dad’s favorite boat. Love is mangy, love is kind, and our love for this artful maniac at the helm most certainly perseveres. — Pat McGuire

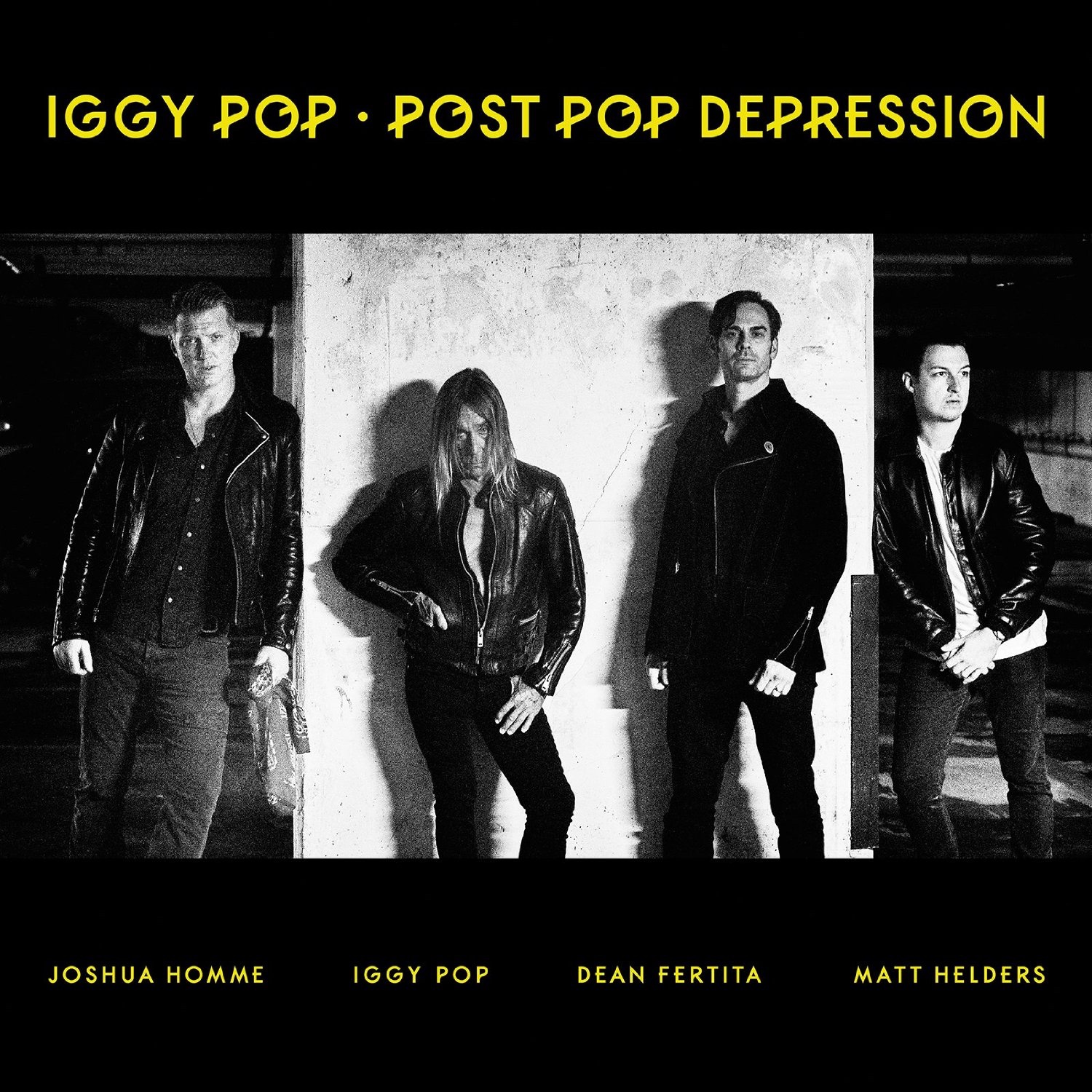

23. Iggy Pop — Post Pop Depression

Any other year, and Iggy Pop would be the elder statesman par excellence. That’s partially because Post Pop Depression—his collaboratory effort with Josh Homme, Dean Fertita, and Matt Helders—was so shockingly effective, and partially because, based on the releases that preceded it, it seemed that Iggy might have been running out of surprises (sorry for doubting you, dude). The album ended up being a monster, and would’ve easily been 2016’s most welcome return to form were it not for old friends David Bowie and Leonard Cohen, who both upstaged Iggy in a way that would have seemed immensely unlikely in 1977: by dying before him. But it’s not Iggy’s fault that he’s tougher than nails. And in a year so overwrought with death, it was a sincere delight to hear someone who had never sounded so alive. — Nate Rogers

22. Xenia Rubinos — Black Terry Cat

The warmth and soul emanating from Black Terry Cat, Xenia Rubinos’s second album, coexist with a fierce awareness. The former are exemplified by the beautiful “Don’t Wanna Be,” wherein Rubinos sings, “Baby, where you’re not, I don’t wanna be.” The latter is evident on “Mexican Chef,” which Rubinos wrote for the people of color who built America and continue to sustain it: “We’re the ones that make sure the tree falls down / When the tree falls down, it don’t make a sound.” People cannot live without politics. Each one’s existence depends on the other. This album is brought to life by the music—which goes from smooth soul to punky dance and back again—and Rubinos’s sweet voice, but to strip it of its social intelligence would be disingenuous, because it’s also an observation of the world we live in. Black Terry Cat is gorgeous, romantic, and true. — Lydia Pudzianowski

21. Cate Le Bon — Crab Day

Cate Le Bon has an unlikely gift: the weirder she gets, the better she gets. For seven years now, the Welsh art-rock provocateur has been sailing out toward the far corners of our expectations, somehow managing to keep the ship upright despite the concerns from us on the mainland that surely the edges must be fast approaching. Not the case. The brave voyage reached new territory on Crab Day, her most profound album to date, itself a manifesto of continued purpose flying in the face of an increasingly mixed-up world. This time, the music was accompanied by a short film, further supporting the fact that clarity of vision is a chief attribute here, and if you don’t like it, there’s the door—er, the lifeboat or whatever. Just don’t be surprised if you end up back in the captain’s room later, sunburned and fatigued, asking to be let back aboard. — Nate Rogers

20. Solange — A Seat at the Table

A quantum leap forward from her past (often very good) work, A Seat at the Table establishes Solange Knowles as an inheritor to Prince, in that she takes her sadness and tiredness and renders it funky and poetic. Over the subdued lock-step of “Weary” she astrally projects her spirit in search of physical relief; in “Don’t Touch My Hair” she boldly demands respect and autonomy; in “Junie” she radiates joy. Album highlight “Cranes in the Sky” stands as one of 2016’s finest moments, in which Solange disposes of concerns and travels “seventy states” only to find her existential concerns have followed her, which only a piercing falsetto refrain of “away” (shades of Mariah!) can properly address. Incorporating autobiographical lyrics and spoken interludes by her parents and Master P, A Seat at the Table offers intimate personal reflections on blackness in America. Its musical ingenuity makes it an art-pop assertion of rage and hope and peace. — Jason P. Woodbury

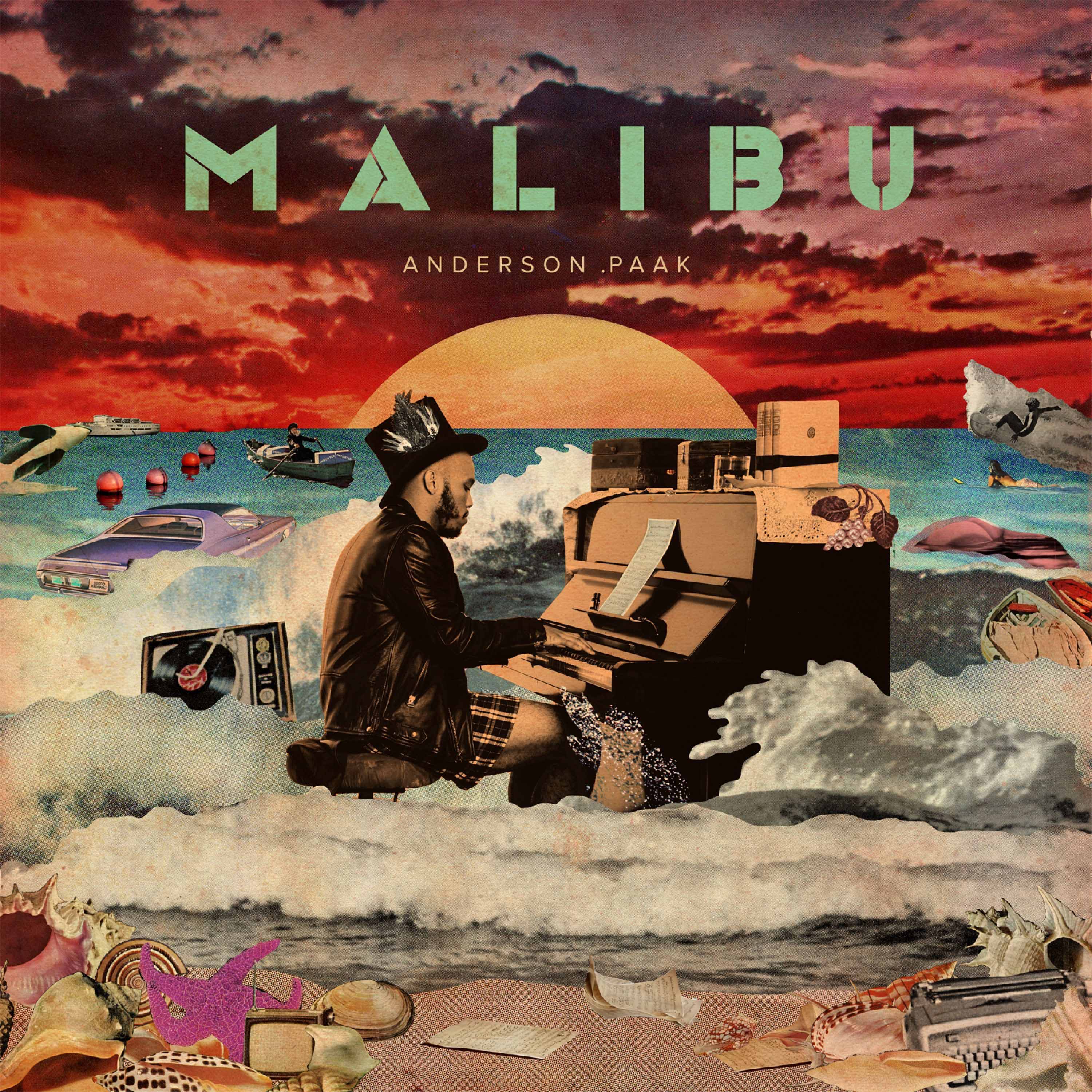

19. Anderson .Paak — Malibu

If Questlove felt the need to wake up D’Angelo at four in the morning to tell him about “Awaken, My Love!”, what did he do when Malibu washed ashore in January? Brandon Paak Anderson released a pair of albums under the regrettable name Breezy Lovejoy, then put his name down, flipped it, and reversed course to create a hybridized version of soul and hip-hop and R&B that feels like a breezy West Coast cousin to D’s own Black Messiah. As with that album, the sense of struggle is never more than a James Brown-ish “huh!” away, but for Paak, who five years ago was living in his car with his wife and daughter, the pain is in the past tense. Malibu, then, is a celebration, the liberating sound of what it feel like to have made it through. — Marty Sartini Garner

18. Michael Nau — Mowing

Michael Nau is one half of the Maryland-based band Cotton Jones, which he has piloted with his wife Whitney for the last decade. Rather than release Mowing as the long awaited third Cotton Jones LP, Nau—formerly of the indie outfit Page France—went solo simply to avoid disappointing fans at shows expecting to see the couple onstage, as the family that the pair recently started makes it difficult for both parents to be away from home at once. Regardless of moniker, the songs collected here are among the most soulful, stirring, and singular of any folk-rock artist recording today. There is ancient wisdom hidden in Nau’s raspy, reaching voice, and a timeless sweetness reveals itself in every nook and cranny of the record. “Unwound” brings to mind the folkiest moments of Workingman’s Dead–era Jerry Garcia, and “Smooth Aisles” twinkles and grooves like a stripped down Steely Dan. There is much joy to be found in Mowing, and a full year into listening to these eleven tracks on repeat, it’s clear there are still miles to go. — Pat McGuire

17. ANOHNI — HOPELESSNESS

It had been six long years since the last Antony and the Johnsons record, but when ANOHNI emerged with a new name and a stark new sound earlier this year, few could have predicted how drastic the change in her music would be. The dark, pulsating electro she creates with Hudson Mohawke and Oneohtrix Point Never on HOPELESSNESS finds her shifting her focus from the personal to the universal and back again, berating the state of the world and the suffering of innocent people at the hands of malicious, power-hungry governments. In “Obama” and “Drone Bomb Me,” she hurls her disgust at American imperialism and the military-industrial complex, but she does so with as much grace as violence. HOPELESSNESS is a bold and ambitious move—one that became all the more relevant as the year marched on. — Mischa Pearlman

16. Parquet Courts — Human Performance

Rock and roll is dying, they say. Dead, even. And when these are your Grammy-chosen representations of the genre, maybe the reports of rock’s death have not been greatly exaggerated after all. But let’s be real: in this, the year of our Lord two-thousand and sixteen, who didn’t die, really? Rock is just another one to bite the dust—and Parquet Courts are currently the best candidate to be dancing on its grave. Human Performance, the band’s fifth LP, is their most realized vision yet of a post-mainstream guitar album, not built on technical prowess so much as a purity of ethos and dedication of spirit. This latest release comes following two statement-laden, melodically-sparse conundrums—Content Nausea and the Monastic Living EP—highlighting a progressivism that has them firmly embedded into the landscape of contemporary intellectualism. Have the rock gods forsaken them? Looks like, but this band never wanted to wear leather pants and play arenas anyway. — Nate Rogers

15. Beyoncé — Lemonade

There’s been a lot of “holy shit” in 2016, but it hasn’t all been the bad kind. Lemonade, while a response to the bad kind, is the good kind. Beyoncé’s masterpiece is a reaction to generations of negativity and oppression, but the fact that it exists is a huge step forward. (It’s also far and away the best her music has ever sounded, but that’s not what’s important right now.) If it takes Beyoncé to make America realize that black lives matter and that women have so much more shit to deal with than men, so be it. Words don’t do justice to this incendiary, necessary work of art; if anything, they only serve to emphasize how much Beyoncé was able to do without having to explain herself. She already did the work. What more is there to say? — Lydia Pudzianowski

14. Preoccupations — Preoccupations

Born out of loss, fractured by controversy, Preoccupations has a track record that implies pure chaos. Which is why it’s rather curious that, despite the universe relentlessly pulling on their seams the way that it has, the Calgary post-punk quartet has somehow ended up with one of year’s most cohesive records. How, exactly? Well, for one thing, there are no traditional rock stars in the band. No big personalities fighting for space. On Preoccupations, every member of the group contributes equally throughout, and with a persistent modesty. So much so, in fact, that when Dan Boeckner shows up on “Memory”—an eleven-minute single (!)—he inadvertently betrays his fellow Canadians by stealing the show, if only for just a few verses. That standout moment ultimately serves the band, however, as it takes you out of your trance for long enough to be reminded that this music is still the work of people, after all—and not some goth supercomputer, like it sometimes sounds. This year, as the forces of nature continued to push against Preoccupations, Preoccupations continued to push back. — Nate Rogers

13. Chance the Rapper — Coloring Book

“I don’t make songs for free, I make ’em for freedom.” On Coloring Book, Chicago’s Chancelor Bennett pushes for all manners of freedom: creative (“No Problem”), sexual (“Juke Jam”), and above all, spiritual (both “Blessings” and its “Reprise,” “All We Got”).

Viewing his music as access to a higher power, Chance espouses a generous religion, one that finds common space for kindred spirits like Saba, BJ the Chicago Kid, and Jamila Woods; surprising collaborators like Justin Bieber; and mentors Kanye West, Lil Wayne, and Kirk Franklin. He brings them all into his kaleidoscopic worship service. Addressing his faith both hilariously (“I might give Satan a swirly”) and poignantly (“Jesus’ black life ain’t matter”), Chance boosts the joyful spirit he brought to Kanye’s defining “Ultralight Beam” to even higher planes.

And when he proclaims “Music is all we got” over the sounds of the Chicago Children’s Choir in the joyous opening track, it sounds like it might actually be enough. — Jason P. Woodbury

12. Whitney — Light Upon the Lake

From two-thirds of the ashes of Chicago’s Smith Westerns came the septet known as Whitney, and thank god they did. The band’s Jonathan Rado–co-produced debut Light Upon the Lake leapt out of the late spring and tucked itself neatly into the melancholy warmth of early summer with enough chiming guitar, breezy horn fills, and slick arrangements to last until next Christmas. Julien Ehrlich’s throaty falsetto may be the band’s true calling card, as it takes the Bon Iver method to left field and leaves it in the weeds to thicken. “No Woman” is a bonafide mix-tape classic, while “Golden Days” and “Polly” could easily be slipped into your hometown radio station’s Seventies Power Playlist without raising any suspicions. As the dreary seasons of 2016 continue to change for the worse, make sure you leave the Light on to guide you back home. — Pat McGuire

11. Kendrick Lamar — untitled unmastered.

Kendrick Lamar’s fourth offering, comprising songs recorded during the To Pimp a Butterfly sessions, could of course be seen as nothing more than an enhancement to his previous works. But to label untitled unmastered. as anything less than a record that stands tall on its own would be doing it and the people it reveres a major injustice.

Situating itself as one of the more artistically poignant rap albums of 2016, untitled unmastered. is an observational study and thoughtful critique of the music industry, race, sexuality, religion, stereotypes, and many other euphemized topics that find themselves woven into the fabric of American life. These varied issues don’t compete with one another for the spotlight, but work together to create a bigger picture. untitled unmastered. further establishes Lamar as the inquisitive person’s rapper, always noting, questioning, and challenging the intricacies of the world that surround him. If it seems like a humble offering, that’s because Kendrick has little to prove to you right now. — Sarabeth Oppliger

10. Frank Ocean — Blonde

In a year marked by loss and tumult, nothing felt more effortless than Frank Ocean’s high-dive splash with Blonde. Ocean has attained a level of artistic and personal autonomy so secure that he pulled his surefire contender from Grammy consideration without flinching. “I ain’t a kid no more / We’ll never be those kids again,” he declares on “Ivy,” indirectly channeling the transcendence of his OFWGKTA roots.

Like more than one of the geniuses who passed in 2016, Ocean is a man of boundless sexual identity. His letter preceding 2012’s brilliant channel ORANGE made this declaration, and there has been a marked sea change in the attitudes of hip-hop ever since. Caustic word rashes continue to feel more and more obsolete, displaced by a resurgence of conscious, analytical, poetic maneuvers. While that Ocean emerged already floating from the chrysalis, Blonde found him stretching out Kodachrome wings, fluttering along to the post-Disney woodwind synths of “Skyline To,” doused with quiet codeine joy.

While the world around us appears set to succumb to great flames, the calm wonder of Frank Ocean was a spot of true beauty in a relentlessly crazy year. It’s a testament to this generational artist’s sagacious ability to see his own face in the throng surrounding him. “There’s a bull and a matador dueling in the sky / In hell, in hell there’s heaven,” he sings. For the challenging times ahead, may we all adopt Frank’s determination to lead by riding…solo. — Kyle MacKinnel

9. Alex Cameron — Jumping the Shark

How much of Alex Cameron is on Jumping the Shark? How well does he know the awful people who populate the album? The answer is either that he is one of them himself or that he’s spent a good amount of time around them. Trying to figure out which is the case made this album one of the most compelling and addictive listens of 2016. How does he know what he knows? How does he make it work so well? The answer to the second question includes synthesizers, reverb, and the presentation of a man alone in an echo chamber.

He’s the lone star of all of his music videos, save for two nameless, voiceless women in “Mongrel.” In these videos, he looks uncomfortable, often sweating and dressed either to the nines or whatever the polar opposite of the nines is. Is this him playing a character? Only he knows—and probably Roy Molloy, who he refers to as his “good friend and business partner.” Of Molloy, Cameron writes, “First time I met Roy he was stuffing lemons in a drain.” Was he? We’ll never know.

Like the characters it spotlights, the album is slick on the outside and morbidly fascinating on the inside. It offers a lot of questions that it doesn’t answer and a lot of talent that makes those unknown answers irrelevant. Regardless of where Cameron’s been, Jumping the Shark makes it possible for us to pay a visit that haunts us long after we leave. — Lydia Pudzianowski

8. Kanye West — The Life of Pablo

Kanye West’s magnum opus is an uninhibited exhibition of the self—in all its grotesqueries and graces, its fantasies beautiful, dark, and twisted. Its greatness lies in willful contradiction and a brash amplification of the author’s divisive voice. Where the subjects of West’s last two albums—the croissant-demanding deity of “I Am a God” or the sex-starved pharaoh of “Monster,” say—tended toward tweaked and exaggerated versions of Kanye, The Life of Pablo returns to the self-narrativizing of his classic first two albums, all with the added benefit of a decade spent expanding the boundaries of the hip hop genre, and popular music in general.

While some have labeled it Kanye’s “messiest” album, it’s a model of Ye at his most songful: the prog influences of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy are employed without track lengths ballooning (“FML”); the industrial affectations of Yeezus are grafted to swaggering, grooveful anthems (“Feedback”); and soul sampling blossoms into an original gospel-fusion track (“Ultralight Beam”).

Of course, all that compositional sophistication stands in contrast to the bald-faced ignorance of a lyric like that irksome Taylor Swift line, or the “Tribe Called Check-a-Hoe” joke, but let me ask you: how much are you enjoying that new J. Cole album? Art benefits from personality, and while Kanye’s recent tour cancellation and mental health scare suggest his mania is no mere performance, on The Life of Pablo, it contributes to a compellingly dense vision of hedonism and vulnerability. Blatant provocations of disgust exist alongside humor (“I stuck to my Roots / I’m like Jimmy Fallon”) and pathos (“You ain’t never seen nothing crazier than / This nigga when he’s off his Lexipro”), making for an album that’s far from balanced in its emotional exhibitionism—but that imbalance is as sincere as it is galvanizing. — Sam C. Mac

7. David Bowie — ★

Like a warning shot, 2016 began with one of our biggest stars falling from the sky. Yet with David Bowie’s unexpected departure also came a tangible sense of hope to cling to: in his own inimitable way, Bowie turned his death into art.

★ was released on January 8, Bowie’s sixty-ninth birthday and only two days before he died. Fittingly, it’s a powerful rumination on mortality and what it means to be alive. Its songs are full of a transcendental, spectral power, and an otherworldliness that made even more sense on the tenth than it did for the two days prior. Harrowing and inspiring in equal measure, it was a welcome reminder that despite the darkness, the sadness, and the lacuna that death always leaves behind, there’s still beauty and love in this world.

Of course, this being Bowie, ★ is hardly sentimental or saccharine—rather, the album’s seven songs provide a weird and disconcerting journey to the other side, wherever that may be. With their intermixed grace and horror, the likes of the title track and “Lazarus” sound as if they were created with prior knowledge of what lay behind the existential curtain. Of course, if anyone could say what happens beyond our time on earth, it was probably Bowie, and this phenomenal swansong of a record still serves to remind the world of his unique and transcendental power. — Mischa Pearlman

6. Andy Shauf — The Party

Andy Shauf’s 2015 debut, The Bearer of Bad News, announced the arrival of a new talent possessing more than a passing fancy for the darkened pop chime of Elliott Smith and Paul Simon. But on the Saskatchewan-based musician’s 2016 ANTI- debut The Party, his subtle and gorgeous tunes capture the characters, ebbs, and ending of a run-of-the-mill suburban fete with all the mature songwriting sensibility of Harry Nilsson or Randy Newman and the sharp eye of a wizened wallflower enjoying a cigarette break.

Listen as clarinet, piano, and strings rise and fall through the steady, slow clip of Shauf’s confident tempos and charmingly unique and at-times mush-mouthed delivery. There are sure-footed spaces of uncertainty in the album-launching “The Magician,” sunny and upbeat AM radio pop in “Begin Again,” moments of heart-worn mortification in “To You,” and sparse lulls of sweeping majesty in “Martha Sways.” While Shauf’s party is not necessarily one for the annals of Instagram’s “Explore” tab, it is no doubt an affair to recognize, and to remember. When he asks “Are you running around or just running away?” in the jangly cynical “The Worst In You,” it’s recognized as a cry that each of us have no doubt bellowed from some half-dark hallway of our youth. — Pat McGuire

5. Leonard Cohen — You Want It Darker

Leonard Cohen knew that he was dying, but he did not know while working on You Want It Darker that it would be his last album. While it’s difficult not to hear it as one final thanatopsis from death’s finest lover, it’s nevertheless incorrect to do so, and besides, Cohen would never be so morbid; he had more style than that. Rather than being a clear-eyed examination of the life of the world to come, You Want It Darker is instead a nearly perfect re-examination of all of the themes Cohen visited in a lifetime of song. He greets each like an old friend—he seemed to greet everything like an old friend—and dances his familiar dance.

But as anyone who was fortunate enough to see Cohen perform knows, he was an old dog in love with new tricks. While his later work frequently found him using Christian imagery to make Buddhist observations from a Jewish perspective (truly; see 2012’s “Going Home”), here he sounds disappointed and burned out—though without losing his reverence. Romantic and spiritual love are conflated, as they often are for Cohen, but he has little to offer his subject other than a consuming and palpable sense of regret.

And yet, You Want It Darker never feels like a work of negation. Perhaps that’s owing to the production work of his son Adam, whose lush orchestration makes this the best-sounding album of Cohen’s late career. But it’s also because even when his songs are at their most bleak, they never feel like the product of malintentions; they are instead clear-eyed acknowledgments of limitations—his own first and foremost, though not solely—and a promise to search for a better way. — Marty Sartini Garner

4. Angel Olsen — My Woman

By definition, typecasting is a problem associated with the film industry. But it’s arguably just as much of a problem—if not more so—in music, where confounding artists like Angel Olsen will sometimes go their entire careers without shaking the first impressions that they provided to the public.

For her part, Olsen arrived—on Half Way Home, her full-length debut—with a bare, confessional sound, and was quickly turned into a posterchild for heartbreak and confusion in exchange for her troubles. Two years later, on Burn Your Fire for No Witness, she dialed back the yodeling and dialed up the sense of humor, but her reputation remained largely unchanged. What would it take, then, for her to move forward in the public eye? What would it take for her to break the typecast? Well, what it took was My Woman.

Olsen’s third album is the long jump of the year—a near unbelievable product of artistic growth, instantly ushering her into the critical realm of some of the biggest names in music. Gone is any excuse for two-dimensional readings, and in its stead is a requirement to try to understand a figure bursting with depth not just as a songwriter and a singer, but as a bandleader as well. It’s The Everly Brothers filtered through the lens of someone who grew up singing along to Mariah Carey and Destiny’s Child, your first love remembered from the altar of your wedding. In essence, it’s complex. And whatever ends up being Angel Olsen’s next part, there will be no preconceptions. — Nate Rogers

3. A Tribe Called Quest — We Got It From Here… Thank You 4 Your Service

They have little interest in movin’ backwards, one song tells us, but by then we hardly need persuading: this great, improbable, and final Tribe Called Quest album opens with a one-two punch of not-so-distant-future dystopias, the first one a madcap space colonization where there’s no room for the marginalized and the vulnerable, the second an authoritarian’s reimagining of the Bill of Rights. You know: flights of fancy! But the key line in those two songs is the most down-to-earth and sobering: “We’re stuck here.” So we are. Might as well make the most of it.

And they do. The gang is all here: Q-Tip as adventurous as ever, Phife rapping his ass off from beyond the grave, prodigal Jarobi exponentially multiplying his list of recorded Tribe appearances, Muhammad (my man) grounding Tip’s imagination in knotty funk, Busta Rhymes and Consequence tapping into the unmistakable vibe that’s going on here. This is a record that’s haunted by loss and braced against an uncertain future, even as it collides with a troubled past—but the damn thing just keeps moving forward. It’s the messiest Tribe album by a mile, teeming with joy, big ideas, and a will to make every word and every beat count.

It’s impossibly skillful in how it captures their spirit without recalling any Tribe album in particular. It’s their aesthetic updated and expanded, denser and grimier, swampy where their classic albums are crisp and airy. Every song offers profound pleasure and fearlessness. My favorite moments tend to be the tag-team raps, whether it’s Tip and André 3000 going back and forth on “Kids…” or the full gang holding a roundtable on “Dis Generation.” Yours may have more to do with the production: Jack White’s guitar squall, Elton John’s solid wall of sound, the samples, the grooves, the killer pacing and momentum. They knew they had to make this one count.

Of course, I don’t know that any record can avert the kind of crisis that the opening salvo predicts, but I do know that hearing Phife lay claim to the nickname “The Donald”—because the man once known as “Don Juice” can—gives me hope. We’re all in this together. And the hour is never too late for a left-field surprise, a masterpiece of love and inclusion, or a dance party at the world’s end. — Josh Hurst

2. Radiohead — A Moon Shaped Pool

Stanley Donwood’s artwork for A Moon Shaped Pool contains within it all the micro and macro dimensions that Radiohead’s music inhabits. Sitting there on the cover is the titular pool, cosmically swirling, suggesting a landscape of tremendous size—possibly alien. But there’s also a face, monstrous in proportion, intimidating in its vacancy—like a portrait of the astronaut cousin to the Dick Tracy villain The Blank. “A frightening place,” Thom Yorke sings on “Glass Eyes.” “The faces concrete grey.”

It’s a cold world out there, and it’s only getting colder—or hotter, as it were. And as we all continue to cook together on the global level, we still mill about on the personal one, because what else can we do? Since Radiohead’s ninth LP arrived in May, Brexit and Trump have shaken the Western world with the ramifications of a post-truth society, calling into question both the feeling of concern as well as the feeling of futility that tends to follow it. (In all of 2016, was there a more prescient line than “The numbers don’t decide / The system is a lie”?) It’s a vicious cycle of fear and anxiety, and for those afflicted, it will likely never totally dissipate.

Radiohead haven’t exactly been a beacon of hope and sunshine at any point in their career, but it feels as though they have now reached their darkest depths. Apart from the themes of a looming environmental catastrophe running throughout the album, there’s also the factor that this is the first Radiohead release since Yorke split with the mother of his two children, whom he had been with for nearly the entirety of the band’s existence. Knowing this, it’s often unclear as to whether his lyrics concern the world at large or his own individual world (again, the micro/macro), and as a complement, it’s also frequently unclear whether the tone of the band’s playing is meant to sound overtly somber or simply purposeful. Truly, the only thing that is clear in revisiting this set again and again is that A Moon Shaped Pool is the best Radiohead album since Kid A.

In Paul Thomas Anderson’s video for “Daydreaming,” Yorke walks room to room, space to space, opening doors. He does so with increasing rapidity—like he’s growing frustrated, but also slightly frantic—until he ends up in a cave, collapsed next to a fire. The journey supplements a central issue of the album, which is that, despite all of our toiling, we never really do know what it is that we’re searching for. The only thing we know is: be it an ocean or a pool, we are all going back from whence we came. — Nate Rogers

1. Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds — Skeleton Tree

It feels fitting that the best album of 2016 is shadowed by artistic failure. Much of Skeleton Tree was written and recorded before the death of Nick Cave’s fifteen-year-old son Arthur. According to director Andrew Dominik, whose film One More Time With Feeling follows Cave and The Bad Seeds in the weeks after that horrible event, the grief-stricken singer, who over his forty year career has never lacked the words to describe much of anything, was virtually unable to return to his desk. Only one of Skeleton Tree’s songs was written after Arthur fell from a cliff outside of Brighton, and when the band returned to the studio two weeks later, they eventually decided to focus on refining what they had already put together.

There’s no way of knowing which of the sounds on Skeleton Tree were recorded after Arthur’s death, and the opening line’s reference to someone crash-landing in a field near the River Adur (itself near Brighton) aside, Cave never mentions his son directly. The source of the album’s pervasive darkness, then, is necessarily unclear. At times it feels as though Cave is reluctantly drawing back the curtain shielding us from the heretofore unknown depths of horror that exist in the world every day, that he merely got there first. That is an incredibly attractive concept in a year so characterized by despair.

But to define Skeleton Tree entirely by the miasma that lurks in its every corner is to miss its foundation: love. Cave has spent his career circling the love song, drawing portraits saccharine, threatening, and doomed. For Cave, love has been a transaction, a way of asserting power or of being dominated, and a cause of desperation. Here, though, it’s life’s only source. He stumbles through the album, gasping for breath in an apparently loveless universe; grief, we see, is a kind of asphyxiation.

Love does not only exist here in absentia, though; it also comes in the form of support. The Bad Seeds’s cresting vocal harmonies lift him up in the chorus of “I Need You,” their soaring beauty temporarily drowning out the menacing synth pad that’s otherwise followed him throughout the song. On “Jesus Alone,” they gently clatter, giving their leader space until their individual sequences begin to sound like soft finales; it’s as if the individual Bad Seeds are trying out endings, each one doing their best to coax Cave away from the oscillating vacuum at the center of the song. Like Job’s friends, they bring comfort, however inadequate that comfort may be.

There is no easy solution—not for Nick Cave, and not for any of us. The light comes in somewhat naturally, if furtively and obscured. “They told us our gods would outlive us,” he sings in “Distant Sky,” “but they lied.” That he’s even able to make such a concrete statement after half an hour of abstract keening feels like a kind of victory, however bitter it may be. He sings of the sun rising in his beloved’s eyes as they set out for new territory, and this knowledge seems like enough to carry them for now.

When we speak of darkness, we imagine it ending, dawn breaking, and a new day rising to reveal a refreshed landscape eager for renewed cultivation. We imagine that we’ll go back to who we were. To be sure, dead wood and skeleton trees are the last stop on the cycle, with new life just a seedling away. But that’s the thing about new life: it only contains a kernel of the old life. To try to live any other way would be a failure. — Marty Sartini Garner